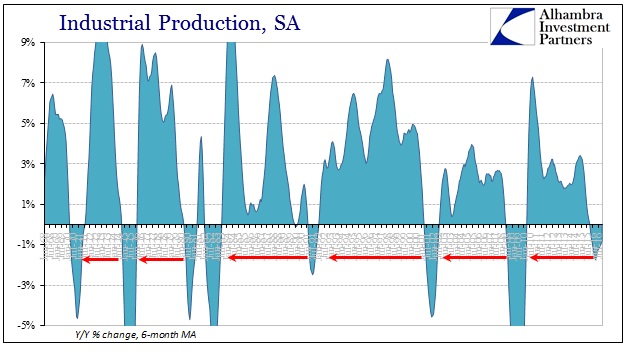

Last December, the Federal Reserve confirmed that it thought its monetary task was nearing completion but under conditions that’s its own data showed were nothing like recovery. In simple terms, they declared recovery and recession simultaneously on the exact same day. In orthodox economics, that isn’t actually impossible, though we have to define both terms. The factual basis for each element was first that the FOMC voted to raise the federal funds even though, second, one of the primary economic statistics in the mainstream catalog, industrial production, with a history predating even the 1920 Depression, turned negative for the first time this “cycle.”

A negative result for IP is relatively rare, typically observed only during past recessions. The data has been revised during the intervening year, now suggesting that the contraction and overall weakness actually began sooner than last December. For their next trick, in a repeat of last year, the FOMC again on the same day votes for another rate hike while the Federal Reserve staff reports its IP statistic that now leaves no doubt there is “something” drastically wrong with the US economy.

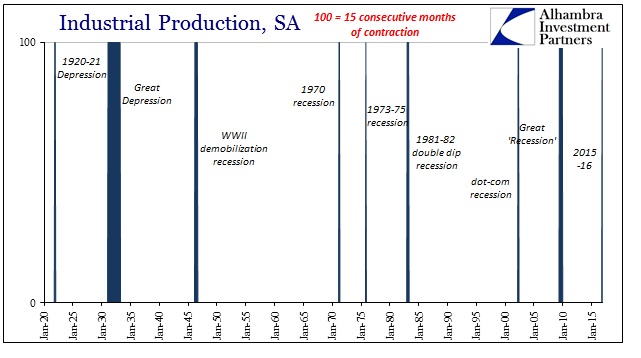

The depth of the sustained contraction is not the primary element of it; it is, rather, the length and that even after 15 months straight shows no signs of changing. That is what should be concerning for people beyond policymakers (they have their own rationale, which I’ll get to later), as 15 minus signs in a row is exceedingly rarer still.

The series for industrial production holds estimates all the way back to January 1919. In the almost 100 years of data, 1,175 monthly entries, contraction spanning unbroken across 15 months has happened only nine times, including the latest outburst. The NBER defines 17 completed business cycles during that century, meaning that nine officially declared recessions didn’t even produce that length of contraction for IP.

All of those periods that met this comparison were associated with recessionary periods – except 2015-16. I wouldn’t describe the past two years as recession, either, suggesting instead by this evaluation and several others like it that the US economy has been dragged down in serious and sustained fashion so that significant parts of it have experienced conditions like recession. That it shows up in the history of something like IP in rarified historical company, on the very negative side, demonstrates too well that this is a very serious and highly unusual deficiency rather than just some bland, nondescript weakness that every economy everywhere must deal with from time to time.

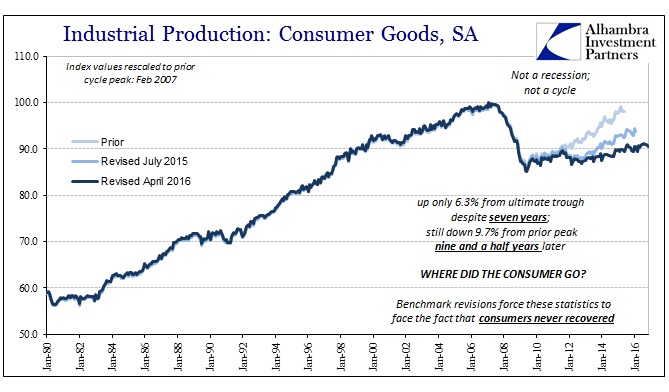

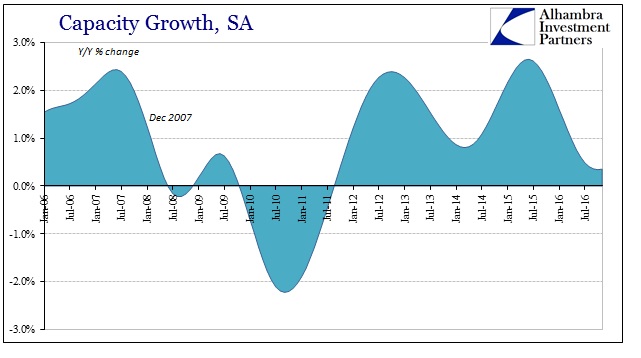

I believe the shallow nature of the sustained contraction is a product of the overall trend; i.e., depression. The US economy, as the global economy, never really recovered from the Great “Recession” therefore there wasn’t a whole lot of upside for this downside to revert from. That point is demonstrated best by IP for consumer goods.

As is perfectly clear from the chart above, US consumers never recovered, meaning one less factor that in a normal business cycle would very likely have pushed IP down further to levels more consistent with shallow, full-blown recession. Because consumers are left out of the variation, overall industrial production is being driven by business capex alone.

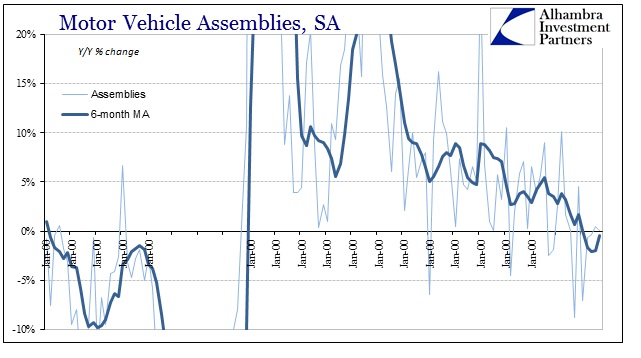

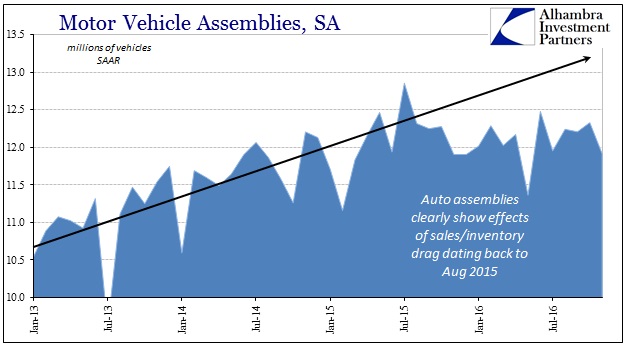

This isn’t to say that all remains positive, if slightly positive, for the production of consumer goods. In terms of automobiles, the Fed’s IP data continues to show a reduction in domestic activity for all motor vehicles. The trend for assemblies clearly broke last summer, an unsurprising development given that what happened in the middle of last year was shocking to both consumers as well as to those who provide financing to them at the margins.

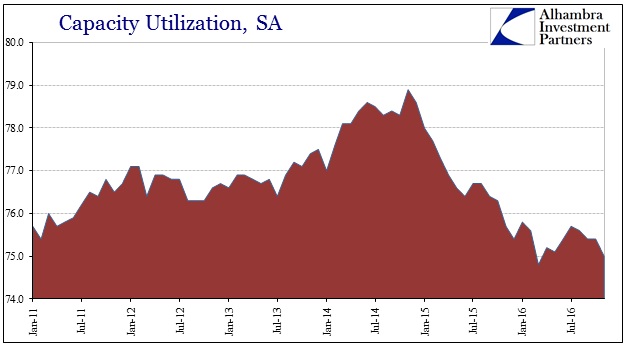

Without the boost provided by the auto sector, which had been one of, if not the only, bright spots in the entire industrial economy, we are seeing again factors like capacity utilization head back down in late 2016 toward recent lows. It was expected certainly in the mainstream descriptions of the economy that by now conditions would be far better than last year, not detectably worse.

Capacity utilization fell back to just 75% in November, not meaningfully different from the 74.8% in March 2016 that I think many have been using as the recent low point (from which “reflation” has been seeded). With capacity in such low efficiency, that will only further weigh on overall capex and productive investment, weakness that will have to be added to what is already evident.

By raising rates a second time, the FOMC is actually confirming that none of this, in their view, amounts to a business cycle, either. It may be counterintuitive, but the standard of recovery has actually been rewritten by the broad and historically significant economic weakness of the past few years. In perverse fashion, the Fed is actually telling you this is as good as they figure it will get.

Last year, IP raised the issue of recession on the day the Fed hiked rates; this year IP all but confirms depression on the day the Fed hikes rates for the second time.

Stay In Touch