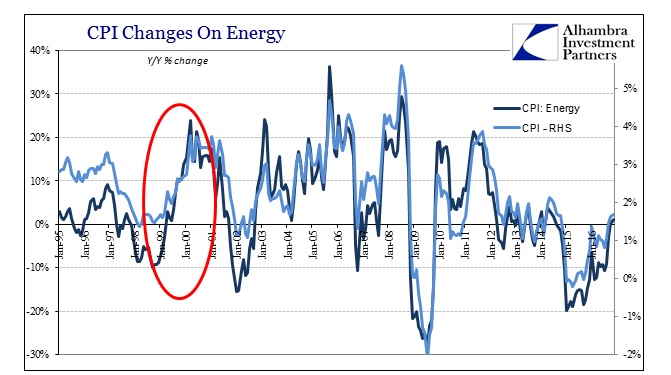

The CPI continued its meandering in November, increasing 1.69% year-over-year in a very slight acceleration to October’s 1.64% gain. As oil and energy prices this year are compared to the worst levels last year, the CPI is brought back up not to what it would look like in an actually robust growth period but rather what it was in the early days of the “rising dollar.” This contrasts sharply with other seemingly alike periods such as 1999.

As I wrote with regard to correspondingly short retail sales comparisons:

The conditional similarities should make these years nearly identical as far as results. The final year of the 1990’s was the last “best jobs market” that the current “best jobs market in decades” refers to. It was also a year where the economy was coming out of an unusually weak period related then to the Asian flu and the slowdown that developed. Oil prices were rising again, and Alan Greenspan, in his crescendo as the “maestro”, began to raise rates that July after lowering them in late 1998 in an attempt to cushion the “overseas turmoil” then devastating much of Asia.

Even if the absolute levels for these various economic accounts start much differently, the patterns should be identical, meaning easily identified acceleration. As oil prices crashed in 1997 and 1998, they rebounded sharply in 1999. The CPI registered a low of 1.4% in February, March, and April 1998, remaining at about that level for just over a year until February 1999. That thirteen months scraping along the bottom was, again, very similar to what happened in 2015-16 when the CPI fell negative in January 2015 and was near zero more or less for the entire year.

Once the rebound hit in 1999, however, the CPI within the next 13 months (by March 2000) had jumped up to 3.8%. That is what you expect to find during periods of an actual rebound and growth: demonstrable acceleration. In the latest results, inflation was figured at 0.50% for November 2015 and over the intervening 13 months it meandered up to the current level of 1.69%. It is less than half the acceleration at less than half the overall level, therefore what appears to be a quite accurate description of the vast economic differences between now and 1999.

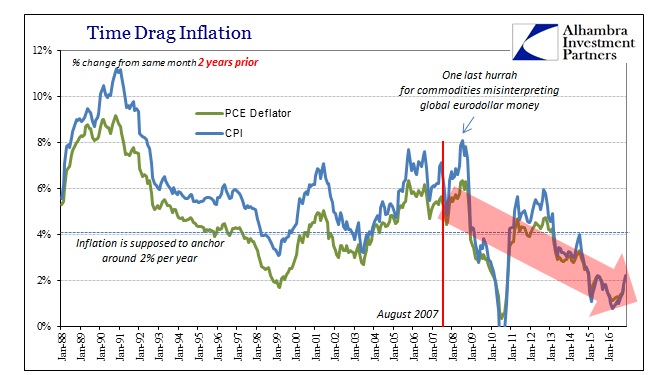

The 2-year change in the CPI, a relative indication of lingering economic concerns (stagnation), was at its lowest rate of 3.07% in February 1999, that was shortly corrected as it shot up to 5.55% 13 months later before peaking at more than 7% into the middle of the dot-com recession in 2001. The current 2-year change is just 2.2%, up from a low 0.78% and clearly nothing like the late 1990’s.

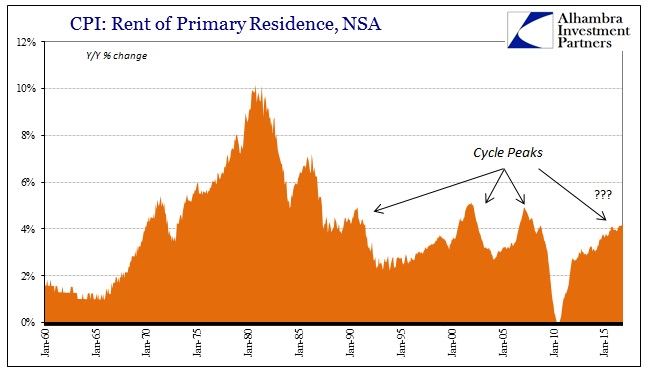

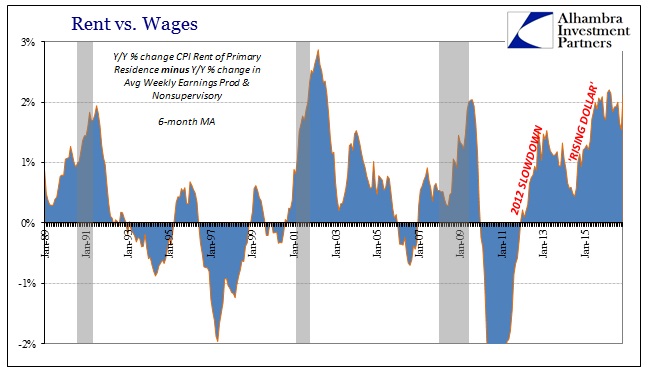

In more pure macro terms, the other relevant comparison continues to be the disparity between rising rent and the lack of wage acceleration. With Janet Yellen and the FOMC throwing in the towel on a traditional, historical full employment period where wages actually accelerate, even economists aren’t any longer looking for improvement.

The CPI for Rent of Primary Residences was up 4.2% again in November, matching for the third time in the past five months the highest inflation since 2008. Average weekly earnings (nominal), however, grew by just 0.4% year-over-year in November, another very low increase that pushes average weekly pay growth back down to just 2% again. That leaves the difference between rent inflation and average nominal wage growth back above 2%, a result usually found at the worst parts of recessions. This doesn’t suggest that recession is imminent, rather it shows why for many people it today feels like there is one right now and has been one for almost two years.

It posits one good reason why there is a lack of acceleration indicated throughout the CPI figures, as retail sales or whatever else. As mentioned several times already this week, the FOMC didn’t actually declare recovery with its second “rate hike”, which would have been obviously and completely inconsistent with all the data. They instead redefined it so that it could be consistent with all these numbers that are in every way incongruent with past recoveries and growth periods.

Stay In Touch