This is a repost; originally published Dec. 22, 2016.

The federal funds rate target is essentially nothing more than a communication tool. You don’t have to take my word for it, the same conclusion has been reached at the level of the FOMC itself. There was, in fact, some debate, though limited in scope, in 2013 and 2014 about changing the monetary policy lever to more accurately reflect how the Federal Reserve intends to “exit” in practical terms. What the Fed ultimately decided was that they would maintain the federal funds target, now a range, not because that is how money markets work and interact with monetary policy but rather because that is how they believe the public perceives what the Fed is trying to do.

The actual work of monetary policy is a ceiling and a floor. The July 2014 FOMC minutes state the way it is intended:

…the IOER rate would be set at the top of the target range for the federal funds rate, and the ON RRP rate would be set at the bottom of the federal funds target range.

There was some concern expressed in that meeting as to the RRP and its actual role, which has been subject of some disagreement and certainly individual dislike since its inception.

In addition, most thought that temporary use of a limited-scale ON RRP facility would help set a firmer floor under money market interest rates during normalization. Most participants anticipated that, at least initially, the IOER rate would be set at the top of the target range for the federal funds rate, and the ON RRP rate would be set at the bottom of the federal funds target range. Alternatively, some participants suggested the ON RRP rate could be set below the bottom of the federal funds target range, judging that it might be possible to begin the normalization process with minimal or no reliance on an ON RRP facility and increase its role only if necessary. However, many other participants thought that such a strategy might result in insufficient control of money market rates at liftoff, which could cause confusion about the likely path of monetary policy or raise questions about the Committee’s ability to implement policy effectively.

The RRP is supposed to aid in firming up the “floor”, as the federal funds target band was in the majority believed insufficient by itself. In a speech in June 2014, FRB Boston President Eric Rosengren detailed how that was supposed to work:

Similar to setting the rate paid on excess reserves, the Federal Reserve could in effect place a floor on how low short-term rates would fall in the marketplace, by setting the reverse repo rate – since investors would have access to the low-risk reverse repo rates and thus be unwilling to accept lower rates of return in the markets. Because reverse repo transactions can involve a broader set of counterparties than just the banking system, this tool might have a more reliable effect on short-term market interest rates.

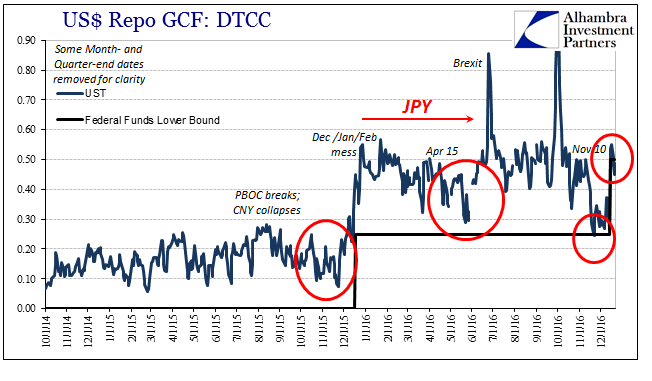

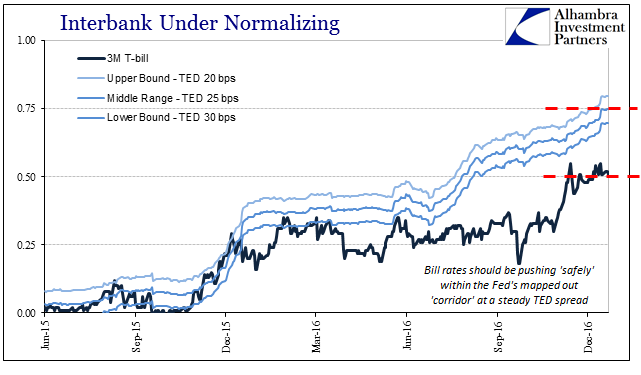

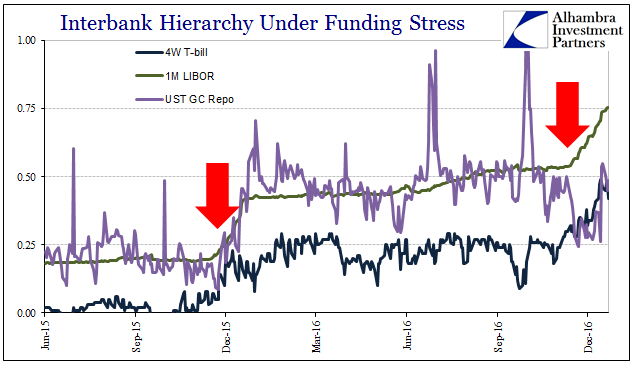

As has become standard practice, money markets seem little bothered by either the ceiling or the floor. As noted a few days ago, monetary policy and its communicative federal funds target range is but a mere reference point. Last year and again this year, T-bill rates have been consistently below the so-called floor despite what Mr. Rosengren suggested. There really is no obvious reason for that, as lending to the US government for 4-weeks at 42 bps should not be preferable to lending to the Federal Reserve overnight every night for 4 weeks at 50 bps collateralized by chosen UST securities.

Similarly, there is no obvious reason why money market participants would lend funds at 44.8 bps GC in private repo markets when the Fed is sitting there with trillions in SOMA collateral paying 50 bps. Yet, that was the GC rate yesterday, and in each of the past three days it has been less than 50 bps in both UST as well as MBS.

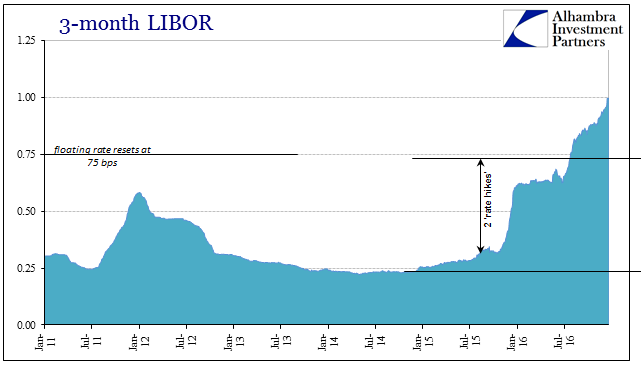

As to the so-called ceiling, we would not expect LIBOR to directly address the upper boundary of the federal funds target range, enforced by IOER, but we should expect some direct and detectable relationship. LIBOR at different maturities obviously carries some time risk that federal funds and IOER do not, but the spread of one over the other should be somewhat consistent if not entirely constant. Instead, LIBOR rates rise “too far” above the ceiling whereas bill rates hug or subvert the floor.

The difference between LIBOR and T-bills at 3 months is the TED spread, and if TED were normal as in pre-August 2007 we would expect the 3-month bill to be near or at the ceiling as determined by LIBOR rather than near or at the floor.

Instead, the bill rate has become intertwined with the GC repo rate; the repo rate previously trading instead in proximity to 1-month LIBOR until the big bond selloff in mid-November (“dollar”). What the FOMC said about the “floor” without the RRP seems to be anyway appropriate as a description of the “floor” as well as “ceiling” with it:

…many other participants thought that such a strategy might result in insufficient control of money market rates at liftoff, which could cause confusion about the likely path of monetary policy or raise questions about the Committee’s ability to implement policy effectively. [emphasis added]

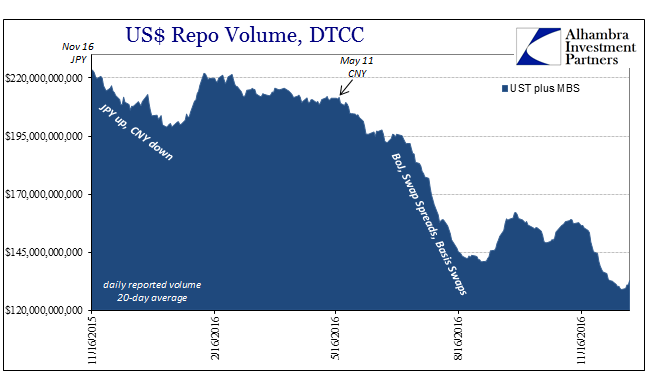

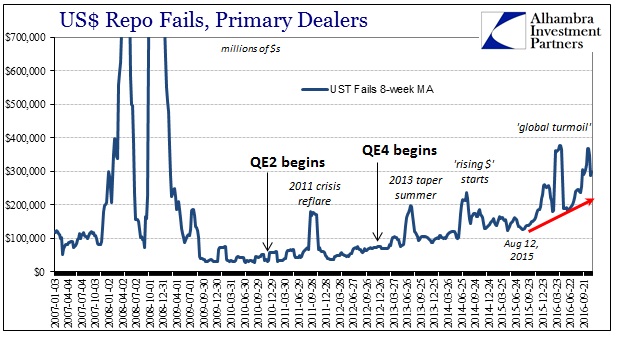

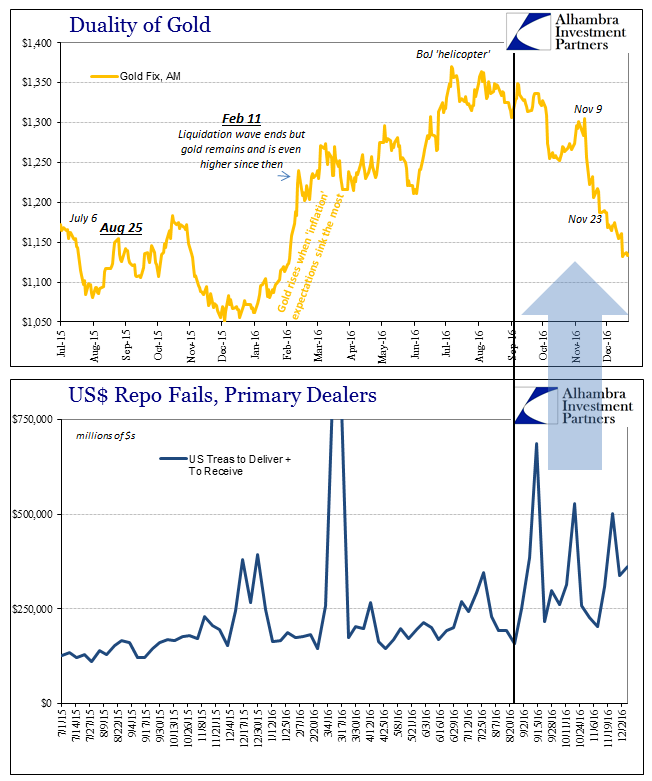

The other element of the RRP is as an alternate means of collateral flow, to open up the vast SOMA holding should spreads rise sufficiently during periods of collateral strain. That has never actually worked, a fact established several years ago and a condition that has only grown over time RHINO’s or not. The level of repo fails alone just in the past few months raise questions about the Committee’s ability to implement anything other than communication. We know very well what the Fed wishes to do, but also have a very good idea about what it cannot.

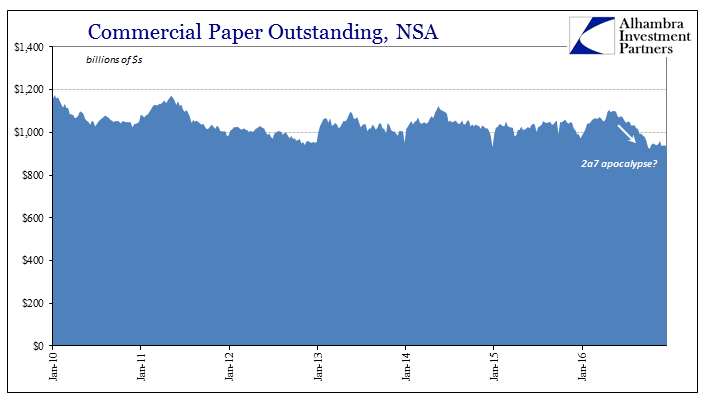

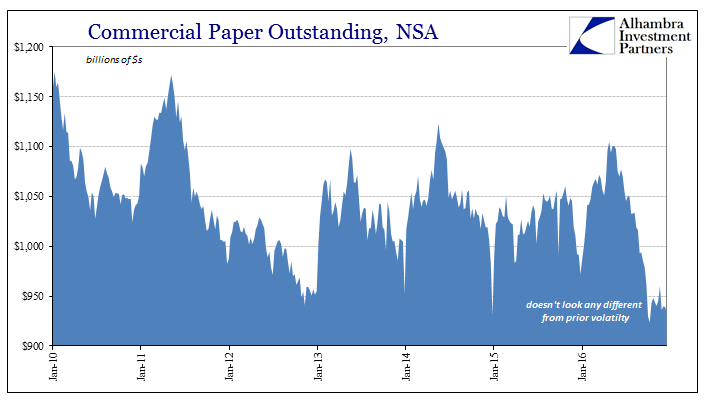

In the months before mid-October, “we” could at least apply the 2a7 label to all this as the benign excuse. But though so much worry was expended to especially commercial paper as the primary 2a7 target, and thus the epicenter from which “reform” would spill out into these other places, like LIBOR, the commercial paper market did seem to absorb some impact, though not really amounting to much of an actual disturbance.

Without the convenience of money market reform, both now as a matter of timing as well as what (limited) effects it might have actually had, we are left in December 2016 with only RHINO – rate hike in name only. These operational constraints are just another dimension to the lack of actual influence of Federal Reserve monetary policy, in close relation to other facets like those exhibited last year as well as in the mid-2000’s. The media gives total deference to the power of the Federal Reserve and its policy, but there is less and less evidence for it. As I wrote last week with regard to the “strong dollar”:

No matter how high Alan Greenspan pushed the federal funds rate, and that was at a time when there was actual volume in that market, he got the “weak dollar.” This time, no matter what the Fed does, add QE, take away QE, increase rates, Janet Yellen seems to be in for the “strong dollar.” Maybe monetary policy and interest rates have absolutely nothing to do with it?

RHINO.

Stay In Touch