In 2003, Nobel laureate Robert Lucas wrote admiringly in his Presidential address for the American Economic Association that the field of economics was itself a put-forward solution to the Great Depression. Such was the calamity that enormous intellectual effort was expanded so as to never repeat it. Though with that belated task there is also, or there at least should be, caution about the dangers of insufficient knowledge. If we are to take Lucas’s history as fact, then can we conclude anything other than economists prior to it were ineffective, insouciant, and ignorant?

Macroeconomics was born as a distinct field in the 1940s, as a part of the intellectual response to the Great Depression. The term then referred to the body of knowledge and expertise that we hoped would prevent the recurrence of that economic disaster. My thesis in this lecture is that macroeconomics in this original sense has succeeded: Its central problem of depression-prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades.

The central innovation, if it may be called that, was his own: rational expectations theory. There is no other way to state it, but rational expectations is a mathematical solution to a problem of infinities. It simply does not exist in the real world, for how can it? To describe it in layman’s terms is to reveal the dodge: economists model consumer and individual behavior as if every single one of us is either himself a social scientist in the same mold, or at the very least has one on retainer so as to consult with for every single economic and financial decision.

The problem is knowledge and the future. We simply cannot know it, and even if we could there is still the non-trivial problem of trying to understand it. In a 2013 Bloomberg interview taken with also Nobel laureate Edmund Phelps, Phelps touched on this glaring inconsistency:

You’re right that people are grossly uninformed, which is a far cry from what the rational expectations models suppose. Why are they misinformed? I think they don’t pay much attention to the vast information out there because they wouldn’t know what to do what to do [sic] with it if they had it. The fundamental fallacy on which rational expectations models are based is that everyone knows how to process the information they receive according to the one and only right theory of the world.

People do act in that manner, if via shortcuts. In the hedge fund business there is, or was, something called the hedge fund “hotel”, where a few “leaders” would be relentlessly copied down to the last possible trade each and every time their 13F was updated (an actual hedge fund hotel is the modern version of the brassplate office). In other markets, including stocks, Alan Greenspan became just this kind of central shorthand for not bothering to understand a good deal of vital information. During the dot-com boom, it was typical to hear managers and especially economists play down every single concern with some variation of “Greenspan will get it right.”

Despite the great angst on the inside of central banks during the 1990s, central bankers themselves became hooked on the idea that they could play that role for the monetary side of the economic equation. As Phelps told Caroline Baum nearly four years ago,

At a celebration in Boston for Paul Samuelson in 2004 or so, I had to listen to Ben Bernanke and Oliver Blanchard, now chief economist at the IMF, crowing that they had conquered the business cycle of old by introducing predictability in monetary policy making, which made it possible for the public to stop generating baseless swings in their expectations and adopt rational expectations.

That was the legend of Greenspan, the man who would “get it right” no matter what. Even after the dot-com debacle, many were quick to return to their religious-like devotion because the housing bubble, for a brief time, anyway, seemed like just the right kind of antidote for the one that had burst. The truth is similar to what Dr. Phelps put forth, as it more natural that people will look to someone else to do the dirty work of understanding complexity. The myth of the Fed has been incredibly popular because modern money is incredibly dense, complex, and in so many ways counterintuitive so as to be nearly impenetrable without enormous time and effort (I write from personal experience here). Better to leave it instead to the “best and the brightest”, for surely they are that.

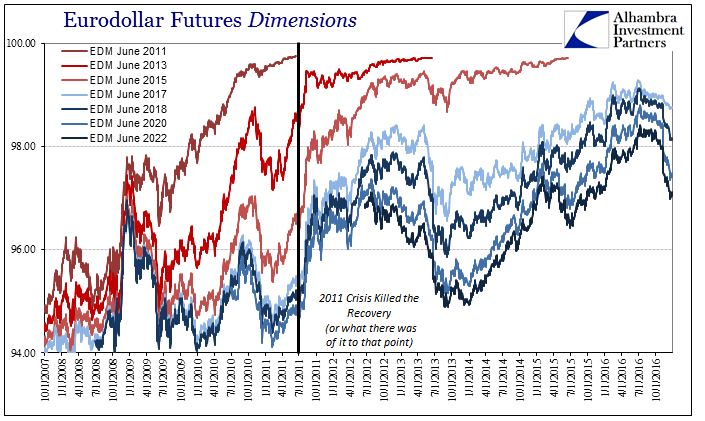

Earlier today, I examined the last decade for the eurodollar futures market as it slowly let the air out of the recovery over an extended period. And the reason it took so long is that each and every time the Fed did something it was immediately embraced as stimulus or money printing; as if the legend of Alan Greenspan was resurrected every time the last genius move failed.

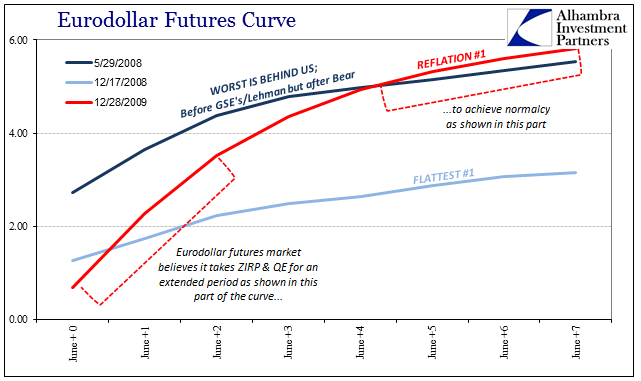

The history of these “reflation” impulses is instructive in that regard – especially what it says about monetary conditions. What were eurodollar investors betting on from December 2008 through to December 2009, as the curve steepened so dramatically? Obviously, it was that QE and ZIRP would work, and that those, along with just the natural business cycle, would lead back to normalization even after massive economic and financial pain.

Given where we are today, those investors were not just wrong but very, very wrong. Rational expectations theory demands, however, that they were not; according to the doctrine, as postulated further by the derived efficient market hypothesis, eurodollar investors have instead reacted to new information in the intervening years such that they have rationally re-evaluated circumstances to the now disastrously low state.

But eurodollar futures are not like stocks or even bonds; they are, or are thought to be, market validation of Federal Reserve policy. Thus, each and every time the Fed was forced to do something and the eurodollar market responded with decreasing belief or enthusiasm for it, the “new” information was essentially repudiation of what are supposed to be the central components of rational expectations (predictable policy) in these parts.

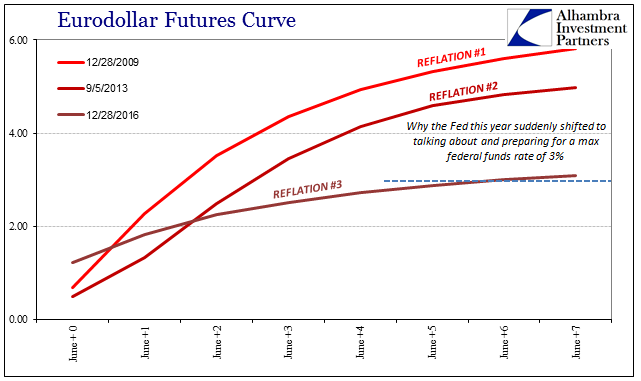

For example, when Ben Bernanke’s Fed felt it necessary to conduct a third QE in September 2012, the “reflation” response less than a year later was noticeably less than the one from immediately after the Great “Recession” and the first QE. At the time, even economists were worried that repeated QE would lose potency; eurodollar markets were instead hedging on a radically different proposition, where if the Fed “had” to do it repeatedly it might be empirically demonstrating it didn’t actually work at all and would not into the future. It cannot be overstated that this is now the position of Fed officials.

Under rational expectations theory, that would mean the “new” information driving markets was how ineffective monetary policy was, or more precisely would continue to be into the rational workings of market understanding of the future. How could effective monetary policy be the rational basis for reflation, but its ineffectiveness the rational basis for its demise? It’s not new information being absorbed; it is reevaluating past principles and beliefs. In his Nobel lecture, given in 1995, Lucas summarized his contributions in this very context:

The main finding that emerged from the research of the 1970s is that anticipated changes in money growth have very different effects from unanticipated changes. Anticipated monetary expansions have inflation tax effects and induce an inflation premium on nominal interest rates, but they are not associated with the kind of stimulus to employment and production that Hume described. Unanticipated monetary expansions, on the other hand, can stimulate production as, symmetrically, unanticipated contractions can induce depression. [emphasis added]

What the eurodollar market has displayed over the past ten years is exactly the highlighted portion of Lucas’s claim. Under his own rational expectations theory framework, the eurodollar futures markets’ “new” information has been to price and accept “unanticipated contraction” in the global monetary regime with an increasing tendency and certainty (especially after 2011).

Each “reflation” trade ended upon the same realization, with amplified (negative) effects after them, that they had been based not on actual monetary “expansions” but solely promises and assumptions for them. The central unifying principle for “market” understanding of money, effective FOMC monetary policy, doesn’t even survive orthodox views of rational expectations.

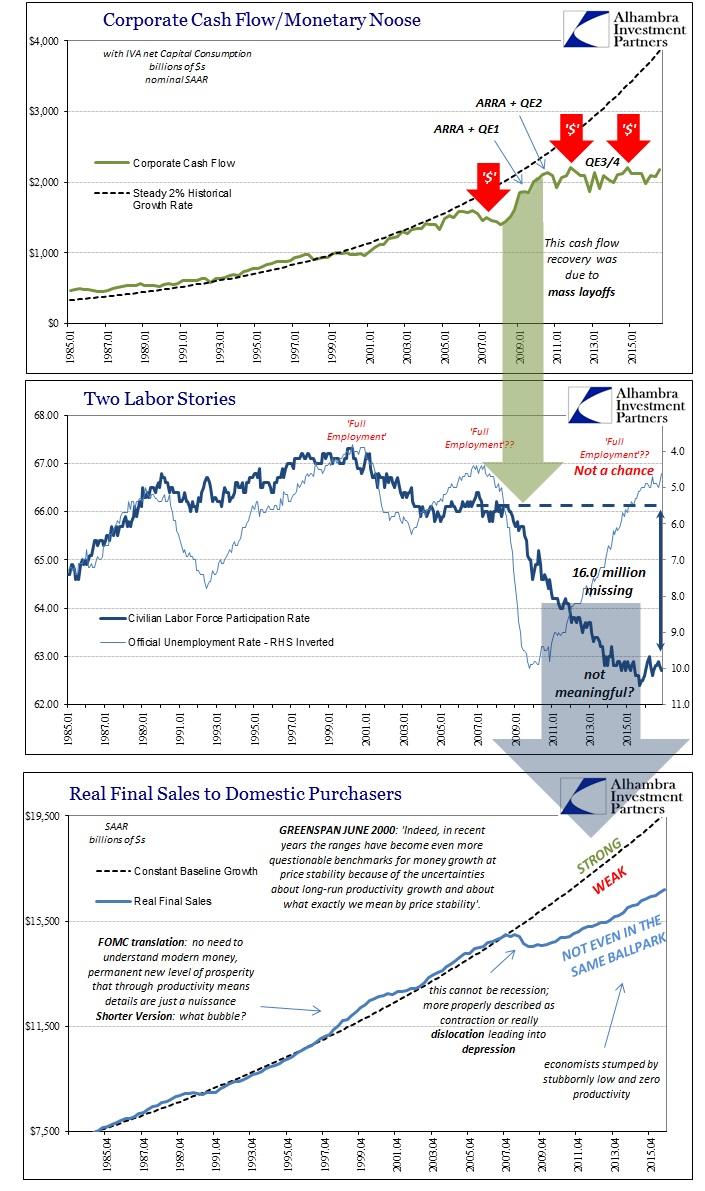

To try to head off reconciling this glaring contradiction, to maintain efficient markets and rational expectations (and no bubbles) as cogent theory survivable in so much failure, policymakers have this year instead shifted the context. QE didn’t fail, they now claim (though it is still significant they no longer maintain it had worked, or will at some unspecified future date), it could not have possibly succeeded. The new equation in the rational toolkit is: QE is stimulus, the economy wasn’t stimulated, therefore the economy is broken (retiring too quickly). Thus, efficient markets supposedly just found out in the past two years that last part as the “new” information (with economists still bringing up the intellectual rear).

What eurodollar futures have done is dispel this tactic ahead of time. The broken variable is not the economy; rather it is, again, the myth of the Fed in sharp contrast from its actual (distant) relation to wholesale, modern money. The equation is far simpler and more elegant: QE is not stimulus, therefore the economy was not stimulated. But it goes much deeper than that, as to even, again, be consistent with Lucas’s Nobel lecture: money markets were surprised to find QE wasn’t money, unanticipated money contraction can induce depression, therefore it isn’t actually a surprise the world has fallen into one.

There isn’t a whole lot that is rational about any of this, starting with rational expectations theory that led economists to substitute legend for competence. Any self-fulfilling prophecy (people believe the Fed is all-powerful, therefore they act as if the Fed is all-powerful, soon it seems as if the Fed is actually all-powerful to the point where Fed officials believe it, too) is doomed the very moment doubts as to its inherent internal contradictions pass a critical threshold. What is rational is the trajectory of eurodollar futures as representative of far more than just eurodollar futures undoing past assumptions, to where the events in 2011 were not new information about money, policy, and the possibly broken economy to perfectly efficient markets, they were just the last straw for irrational belief in myth.

Stay In Touch