Nothing says “fixed” quite like bureaucrats responding to a past crisis they did not foresee (and in the case of European bureaucrats, actively denied while it was happening) by establishing more layers of bureaucracies to “prevent” it from happening again. It is the most predictable result in all of finance and money as the government acting so busily to assure the public by creating rules and shifting power, always to their own advantage. Never mind that no crisis ever repeats, there will always be rules aplenty for the “last” one though never for the next one.

In 2009, European Union officials tasked a High Level Group (that’s the official classification; nothing displays the self-importance and credentialed “acumen” quite like High Level Group) chaired by Jacques de Larosière to come up with ways of protecting Europe’s “citizens” from really matters to that point unknown. De Larosière was a French bureaucrat who was probably the prefect representation of the effort. He had been appointed Managing Director of the IMF in 1978 after spending a decade and a half in French Treasury Department. There, de Larosière had even been a member of the French delegation to the Smithsonian Agreement, meaning that he had no shortage of experience in crafting government solutions that would ultimately accomplish little to nothing of value.

The work of the High Level Group centered around all the usual stuff, the limited hindsight provided by orthodox economists who themselves had very little idea what had happened. As is usual in these cases, they end up throwing a bunch of impressive (sounding) numbers together and stress how these numbers will be useful in the foreseeable future. The result in late 2009 was an unimpressive report that became the framework by late 2010 for the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB). Almost immediately, the European system plunged into renewed crisis that, of course, the ESRB had no idea was coming.

Though the ineffectiveness of the ESRB has actually been established, it continues to publish its numbers anyway. Among them is its quarterly Risk Dashboard, an attempt at a comprehensive review of European banking and money. The first was published at the end of August 2012, and given the situation throughout the two years of turmoil before it, that first Risk Dashboard was given a prominent disclaimer that has not left its pages:

The dashboard is a set of quantitative indicators and not an early warning system. Users may not rely on the indicators as a basis for any mechanical form of inference.

They could not have possibly written otherwise because, as they would later claim, they issued and declared no warning in the middle of 2011 despite all these numbers even though that was their whole job. Instead, the ESRB was busy at that time establishing all the rules and bureaucratic operating procedures that it would use all the while European banks were plagued, again, by a huge degree of risk of systemic shock. It is the means and method of that shock that was and is of great interest.

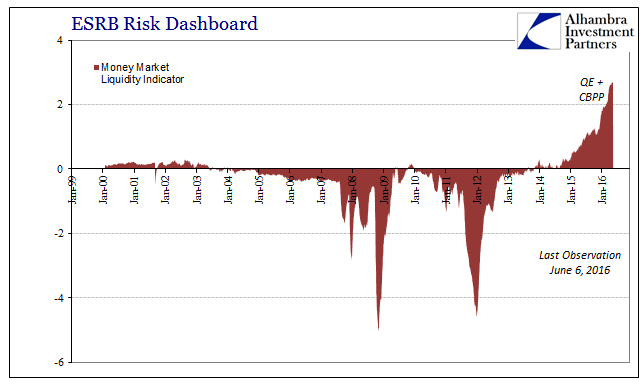

Section 4 of the Risk Dashboard consists of several “liquidity indications”, which are meant to measure funding strains. Among them is one for the European “money market”, showing very clearly the problems in 2008 as well as 2011.

By this view, however, money market conditions since late 2014 are the best they have ever been. The reason, obviously, is ECB monetary policy as it relates to what are still classified as money markets, even though they function in ways that are entirely unlike them.

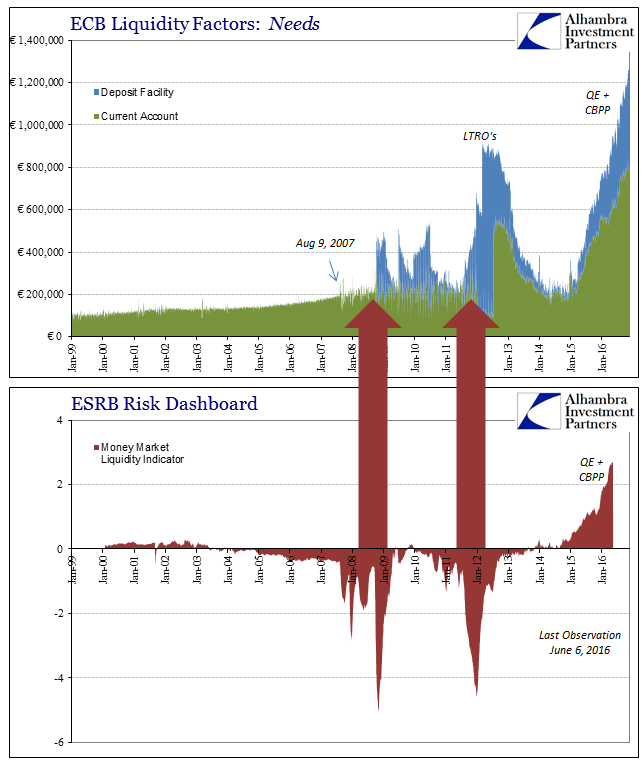

Collating the ESRB number with the relevant parts of the ECB’s simple balance sheet shows that the last few years for European banks have indeed been unlike the prior systemic problems mentioned before.

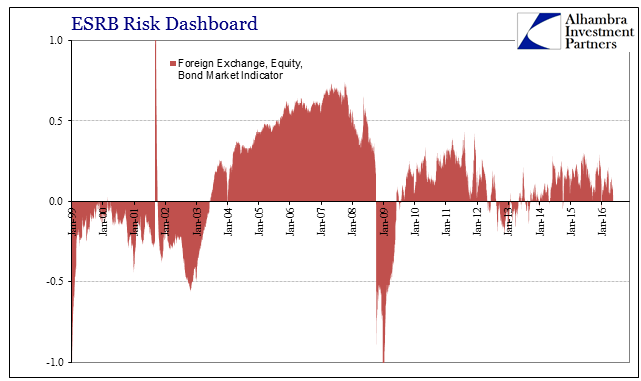

It’s one primary reason why as Deutsche Bank’s stock fell mainstream commentary fixated on the US DOJ settlement as the primary culprit – even though it was European bank stocks in general that were under pressure. If money markets in euros are no longer much like functioning money markets, then it would make sense that stress would appear in other places. The ESRB also produces a separate liquidity measure, though for some reason it is a combination of stock prices, bond metrics, and foreign exchange numbers.

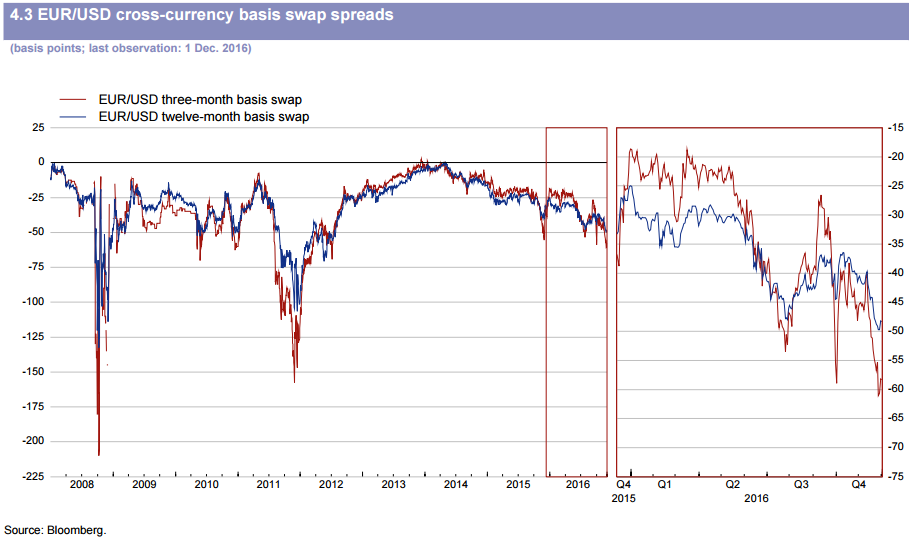

Though no warning is evident here, it is much less ribald than the money market figure. That leaves only cross currency basis swaps as anything signaling any degree of concern.

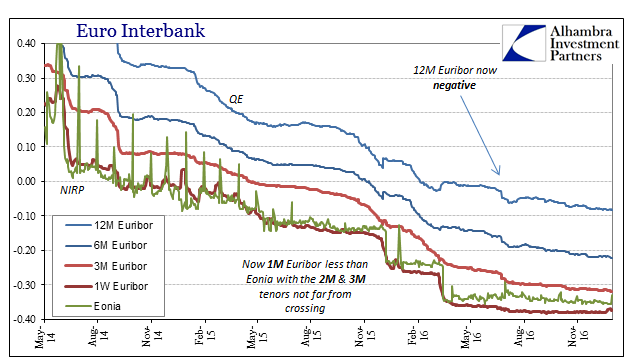

Immediately, you can see the difference with those created quantitative figures, as well as across several additional dimensions. Basis swap premiums for obtained dollars have been falling steadily since the early days of 2014 when, among other things, CNY “unexpectedly” started lower and the ECB decided to “stimulate” with negative money market interest rates and more balance sheet expansion. Unlike 2011 or 2008, basis swaps are not lower all at once; it has been instead a slow burn, an almost steady withdrawal stretched out over just about three years and with no end yet in sight.

The direction of the negative basis swap premiums is the only suggestion necessary; the more negative the premium, the more desperate from the European perspective the European demand for dollars (really “dollars”). It was the spring/summer of 2015 where this imbalance, a systemic one no less, became especially difficult and disruptive. Given the results in the European economy throughout this time period as entirely different from the promises for it, it is safe to write that the ESRB was watching its money market indicator more closely than the cross currency basis swaps that presented European banks, and thus the European system, and thus Europeans, with funding risks primarily of “dollars” than euros.

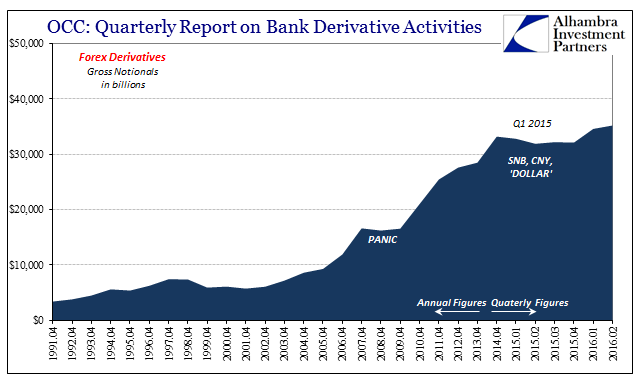

That is the key difference we see from 2011; there is no shortage of euros this time around. The ECB engaged in balance sheet expansion so that European money markets are now highly negative in “yield.” What might be wrong in Europe, then, is outside of euros even though like the ECB the Federal Reserve had itself engaged in large programs of quantitative easing ostensibly in dollars. Therefore, the key distinction that we can observe just in the liquidity portion of the ESRB’s Risk Dashboard for Europe is not between dollars and euros, but rather indirectly between dollars and “dollars.”

In short, European banks are right now more disturbed by “dollar” problems than of anything else. Since that is the only monetary indication of concern and Europe’s economy has acted more consistent with that concern than of anything like QE, then Europe’s economy as well as markets is exhibiting “dollar” problems almost exclusively. It is a good example of the eurodollar system that while in retreat or decay still continues to evolve (though never restore).

That means that what is truly inconsistent across all currencies in the wholesale setting is that bank reserves are nothing more than a useless, perhaps confusing set of numbers without bearing on actual financial conditions. That was true in 2011 and 2012, but even more so now as the temperament of the global “dollar” system has become even more centered around forex than what was still somewhat recognizable as traditional currency formats. The global economy, again, looks nothing like the positivity of the money market indicator but everything like the trajectory of cross currency basis swaps that aren’t even tabulated by the ESRB but are added from Bloomberg.

As poorly as the ESRB has performed (though they would and have pointed out that there have been no systemic failures under their full administration after August 2012, an especially low standard that while correct doesn’t quite meet its own Mission Statement), they have at least included the one set of relevant numbers in their ongoing assessments that you won’t find anywhere near Federal Reserve policy or public discussion of Federal Reserve policy. The ESRB has appeared to have at least grasped that there just might be “something” else going on.

Having focused so much on how the current condition seems a close repeat of 2013, there are also differences that must be factored; though, in the end, they are likely to establish how what followed 2013 is likely to repeat all over again, too.

Stay In Touch