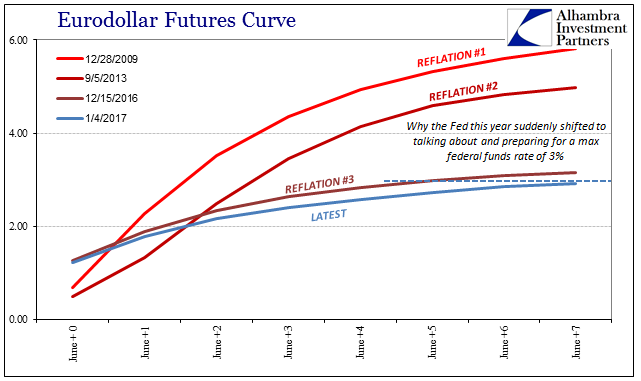

The biggest problem with “reflation” is that it doesn’t live up to what the word is supposed to mean. That has been true in each of the past attempts at it, but is even more the case in this latest one. Yet, to hear it described is as if we are the verge of an explosion in growth unparalleled at least for the past decade. If that were true, we would expect to find widespread, broad confirmation that current conditions are threatening to surpass those past instances.

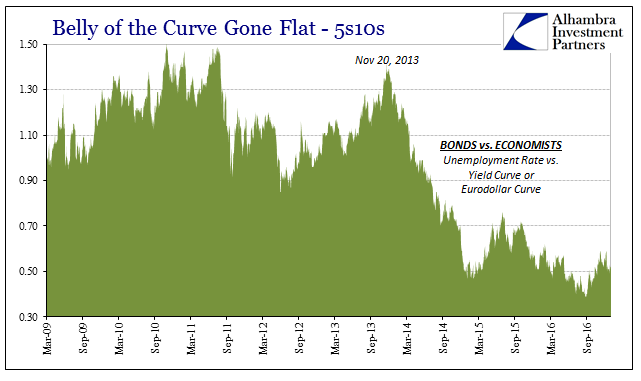

What we find instead is something altogether different, a chance resemblance only in the narrowest of comparisons. The US Treasury yield curve, for one, has barely budged since the flattest, most unbelievably bearish point in July. Nominally, rates are up but the UST market overall just isn’t translating the rise into projected future growth and opportunity. Like monetary policy as it actually is, it’s only a slightly different frame of reference for the same negative outlook.

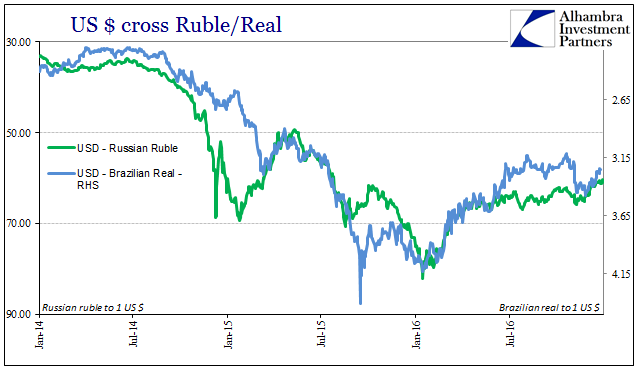

Price after price, indication after indication, we find the same shortcomings. EM currencies, apart from China, of course, have fared far better this year than in the past few. If we observe the Russian ruble, for example, based just on its trading in 2016 it’s as if reflation were possible, maybe even likely.

The Russian currency started the year careening toward a new low, just as everything else including oil had done. To end 2016, by contrast, the currency was moving back close to a 50 handle. Apart from a few setbacks in July and November, Russian fortunes would appear to be on the rise.

Those setbacks, however, and the uncertainty they create, have had the effect of actually limiting the possible revival. Again, relative to early in 2016 things might be looking up, but a more complete survey leads instead to a much different interpretation.

“Better than early 2016” is actually an exceedingly easy comparison, and thus totally inappropriate and misleading given the circumstances. And what are those circumstances? The Russians have tried to quantify them, releasing the results late last month:

Russians’ real disposable income has fallen by 12.3 percent since the beginning of the economic crisis in 2014, writes the TASS news agency, citing a report prepared by the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration. ..

In May 2016 the average monthly salary in Russia fell to $500, which is below the average monthly salary in China, according to Russia’s largest bank Sberbank.

In other words, the “dollar” damage has been done, and the costs to Russians are economic as well as political and social stability (and I don’t mean the ridiculous claim of “hacking” anybody’s elections). What the ruble at 60 says is not recovery but rather at best it isn’t getting worse right now; the Russian economy so far as the “dollar’s” influence on it isn’t being further menaced except for that uncertainty which seems to be the greatest impediment to actual reflation. The ruble here is a signal of further wariness, not reflation.

This is the same mistake being made all over the place, where progress is inferred from only the absence of further erosion or contraction. The error is one being made more so in the media and in commentary (or certain risk assets, though even stocks are more cautious than the related rhetoric) than markets. From the eurodollar curve to the Brazilian real, the same pattern repeats, where this “reflation” isn’t euphorically embraced unlike prior versions. There is far more caution in these prices than optimism.

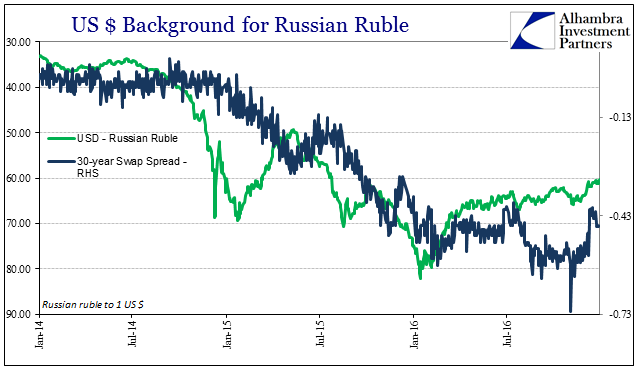

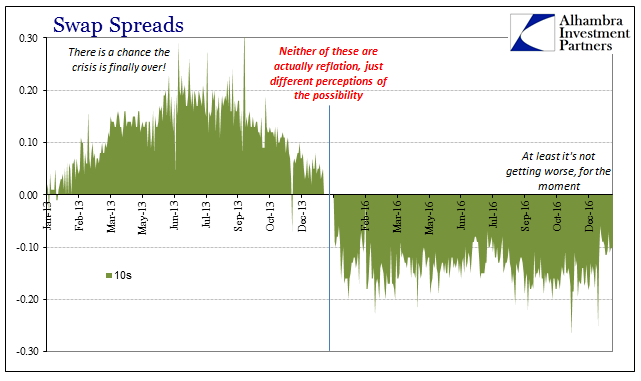

There may be some small comfort in how, at the moment, active degradation is missing, but, again, that is nothing like recovery, reflation, or even progress. The “dollar” background for that view is equally conspicuous to these currencies, commodities, or whatever curve in between:

In traditional terms, those of the binary recession/non-recession template, the end of contraction is the beginning of recovery. The problem for Russia, and everywhere else, is that the end of the “rising dollar” back in February wasn’t the end of the crisis; it was merely the last act in this one part of it. The “rising dollar” is a confusing term because of its imprecision, where it is a both a euphemism for the general “dollar” shortage as well as the specific part of that shortage from mid-2014 forward that brought with it renewed disaster for much of the global economy.

The specific disaster 2014-16 may well be over, and in some respects it surely is, but the overall “dollar” problem is not. That, to me, is the big difference between “reflation” so far in 2017 and that which greeted the start of 2014. Three years ago there was far more registered optimism (if still brief) about an overall end to the crisis that began back in August 2007. This time, all these markets, including currencies, seem to better appreciate the reality of it all; there is a vast difference between pause and conclusion. True reflation would be the latter, but that’s just not indicated anywhere but in the “news.”

Stay In Touch