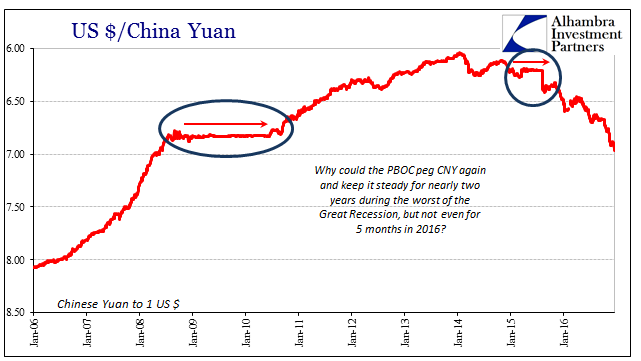

If the groundhog can tell us the length of winter by simply appreciating his own shadow, China’s central bank can perform something of a similar exercise and interpretation about the global eurodollar condition. The panic response of the PBOC is to immediately peg its currency, CNY, whenever a global monetary storm of sufficient fury arrives. Thus, if the PBOC sees the “dollar”, it pegs CNY.

That was the case starting in mid-2008, where after relenting under global political pressure just a few years before CNY was suddenly arrested from its rise against the dollar and left to form a nearly straight line sideways for just about two years. This was during some of the worst global financial conditions in generations, a sufficient monetary storm so as to induce a global Great “Recession.”

Outside of economics, this all came to mind again in March 2015, when the CNY exchange rate was abruptly removed of nearly all volatility, and left to plot that sideways line once more. Given the groundhog analogy, from that we can infer official recognition of severe “dollar” disruption, a condition confirmed by the central bank’s behavior toward internal RMB. Unlike 2008-10, however, this emergency artificiality lasted not even five months; ending spectacularly in mid-August 2015. While Economists were stunned, belatedly wondering about export “stimulus”, it was perfectly clear it was “dollar.”

There’s an immediate incongruity in the comparison, after all, as on the surface it doesn’t seem to make sense that the PBOC would almost perfectly navigate a worldwide financial panic and the severe economic damage that followed but then fail to do the same during much less six years later. It would suggest that, for China at least, the period of the “rising dollar” was possibly that much worse than what we in the West would call the Panic of 2008.

It’s not just our own potential bias of perspective. The global “dollar” system, even in its format of a global “dollar” short, is not itself a monolith. It is (at this time) impossible to determine the exact fragments and define specific parts as specific parts, but it is clear especially in these kinds of historical reviews and comparisons that there are specific parts. I have myself clumsily and imprecisely referred to an Asian “dollar” as a means to display and communicate this reality.

It is quite possible that “our” experience in 2008 was very different from China’s. In many ways, this should not be surprising or even any point of contention. The eurodollar system on the way up was similarly cleaved (at the very least), funding what became the housing bubble in the US and elsewhere (the “demand” side) while simultaneously funding and pushing forward Ross Perot’s “giant sucking sound” especially after the dot-com recession. It’s as if these were separate endeavors of separate “dollars”, though in 2008 they sure came together to find the wrong kind of harmony and unity.

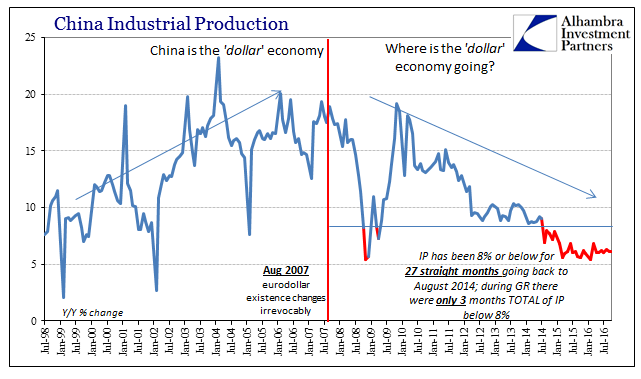

The economic statistics from China bear that out; the Great “Recession” was certainly a major disruption, but it wasn’t anything like it was here, Europe, or even Japan. The “rising dollar” period, by contrast, has been an enormous and as-yet unsolved economic dislocation. It is quite easy to see the Chinese economy in 2016 entering 2017 as much, much worse than 2008 entering 2009.

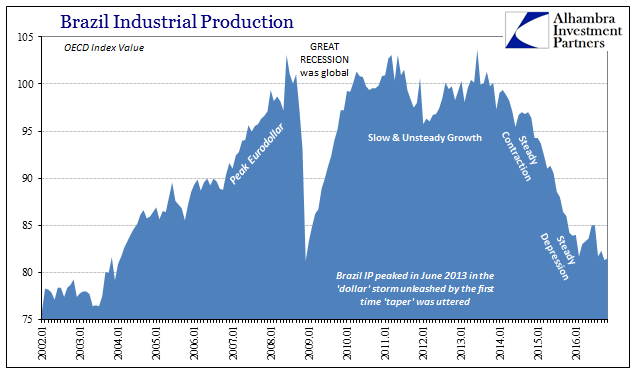

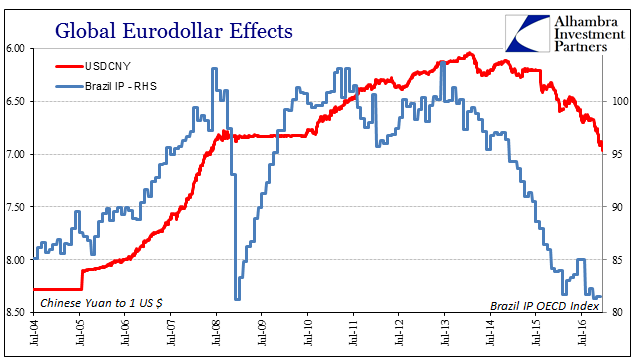

Economists, at least any that pay attention, are as likely to assert this as a problem for and of China alone. Operating under a “closed system” model of the global economy, there aren’t supposed to be any kind of linkages between what are believed to be separate economic as well as financial systems. And yet, the Chinese experience over the past two decades mirrors too closely that of others – such as Brazil.

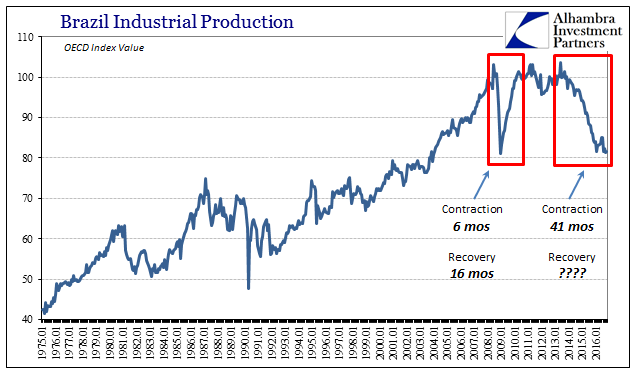

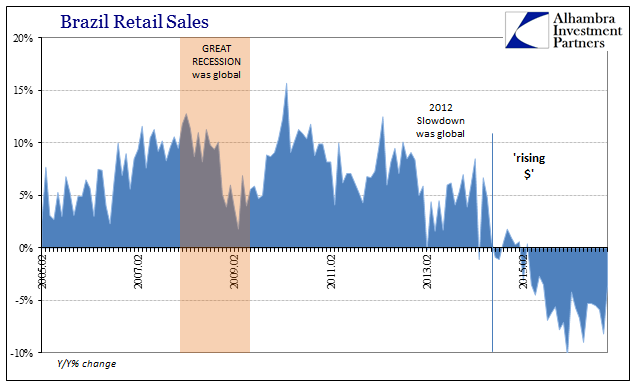

Using industrial production for Brazil, too, we can easily observe the same pattern where it should not be. The Great “Recession” was quite severe in that part of South America, but similarly short and limited. The period after June 2013, however, the first Asian or EM “dollar” rumblings that would become the full “rising dollar”, has been an order of magnitude more severe and catastrophically without end. While IP contracted in severe fashion starting in mid-2008 in Brazil, that downturn finished in just 6 months. The restoration of IP to the pre-crisis peak took only another 16 months, for a total round trip of 22 months.

Starting, again, in mid-2013, industrial production in Brazil has fallen incredibly for 41 months. There was what looked like could turn out to be the long-sought recovery in the middle of last year, but by September 2016, coinciding with “something” in global “dollars”, IP took another turn lower, establishing a new low point by October (and only up fractionally from it in November). It’s not just industry in these various places, either. You can use any number of accounts and statistics that all point to the same processes and the clear commonalities of them.

From the other side of the world, we can confirm and corroborate as to why the PBOC was able to successfully peg CNY starting in 2008, but could only do so briefly in 2015 (and not again since). The “dollar” problem at that time was global, but focused on the “demand” side of the developed world, particularly European banking. The Asian “dollar”, which I would have to include the connection of Brazilian banks as within, was merely interrupted then. From 2013 forward, it’s as if the EM (“supply”) side is now the unenviable focal point, only here the “dollar” is being totally, relentlessly withdrawn no matter what any of these central banks try to do now.

Though the US or European economy might appear to be relatively better late in 2016 and to start 2017, that is only due to the fragments of the global “dollar” system operating separately as they have at various points. In the Asian “dollar” segment, there really isn’t much to be optimistic about, whether China, Brazil, or all the smaller economies caught up with them. This is not “reflation”; it isn’t even the slightest hint of it. It is in some ways 2013 all over again, where “this” side of the eurodollar might have seemed placid enough for recovery biases to be acted out and the brewing Asian “dollar” or EM funding drought to be set aside, ignored, and misdiagnosed. For the EM’s, importantly and relevant to our own future considerations, there is no comparison.

Rather than China being China, or Brazil being Brazil, the various and variable “dollar” segments across the world will at some future date harmonize all over again. As with most economic and financial conditions, there is no sign of the Federal Reserve anywhere here; certainly not in the form of “rate hikes.”

Stay In Touch