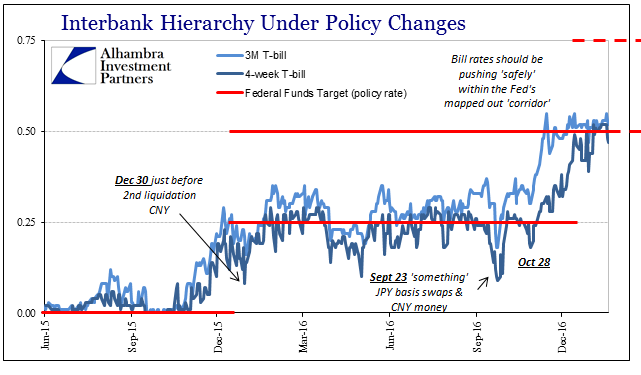

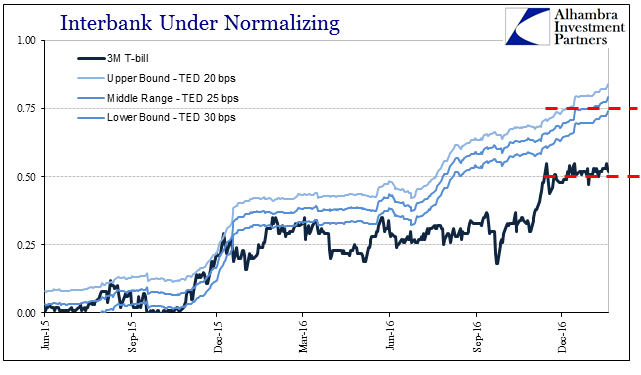

If you are an enterprising financial firm with spare cash toward the end of the business day, you have several options for it. Primary among them is the Fed’s Reverse Repo (RRP) desk which will pay you 50 bps interest with your cash secured by both the reputation of the Federal Reserve as well as UST collateral. Given that option, it remains a bit of mystery, at least in theory, as to why firms the past few days have been instead parking cash for 4-weeks in Treasury bills rather than rolling over daily at the Fed. Coincident to all the intense Chinese money market action, US bills have been shallow again. The 4-week tenor closed at just 46 bps equivalent yield today, below 50 bps each of the past three days; the 3-month bill was just 50 bps today. Neither of those rates makes a whole lot of sense starting from the vanilla view.

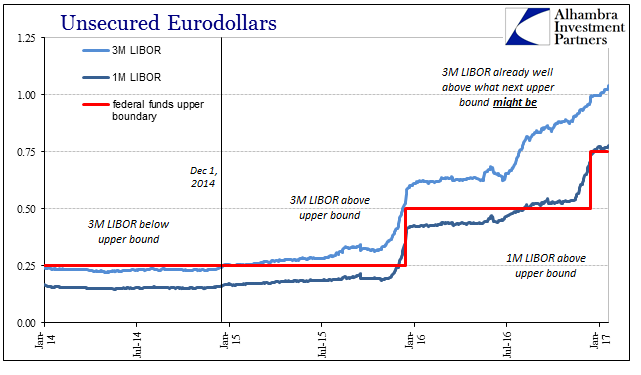

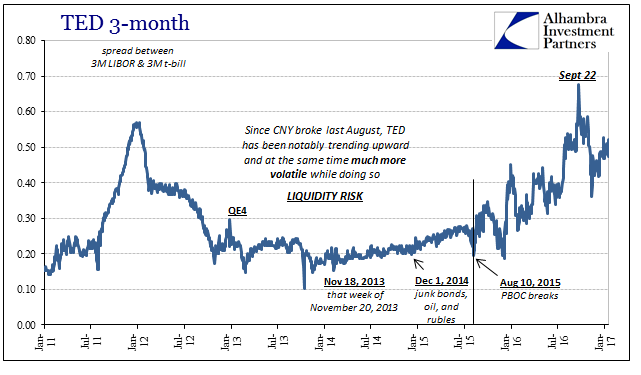

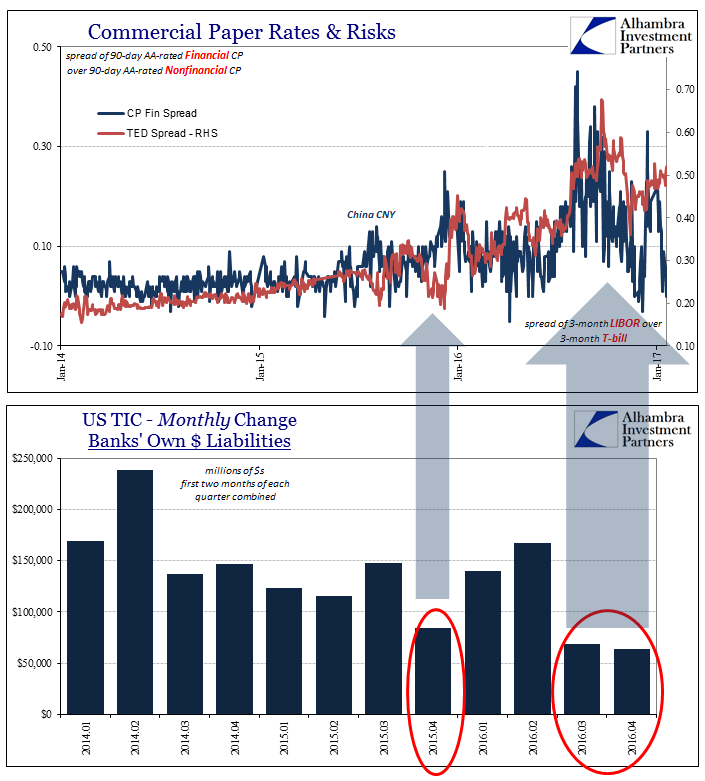

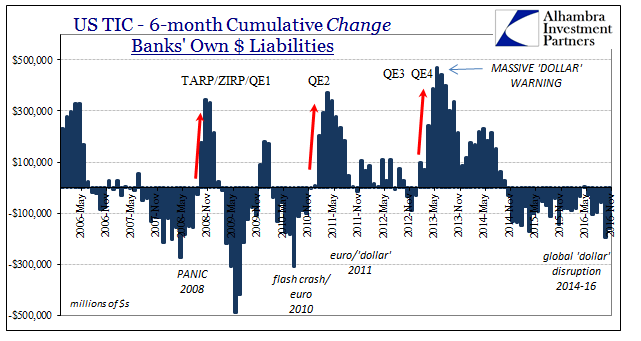

Opposed to that action has been unsecured lending in London eurodollars. Like everything else except T-bills, in the past few days LIBOR rates have moved up by more than the usual creeping. The 1-month rate closed yesterday at 77.6 bps, while 3-month LIBOR was up 1.7 pips in those two days to 104.1 bps. As always, when LIBOR is up and bills down that means the TED spread is decompressing. At more than 52 bps, TED is back to about where it was in October.

That means either bill rates are far too shallow or LIBOR too high, either indicating rising risk more likely liquidity than credit. If we take LIBOR as the proper market view, then the 3-month T-bill should be (equivalent) yielding between 74 and 84 bps. Clearly “something” isn’t right.

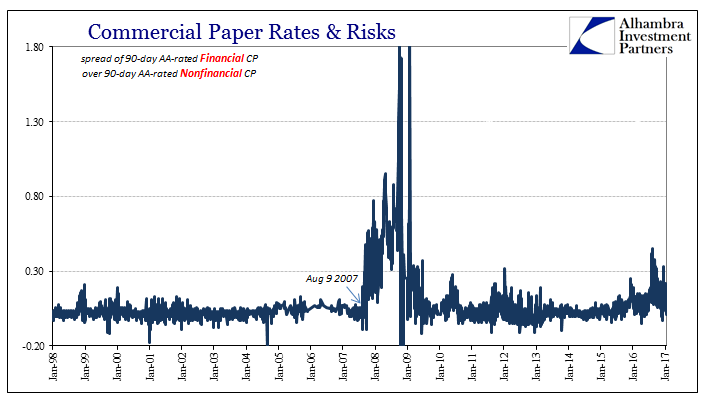

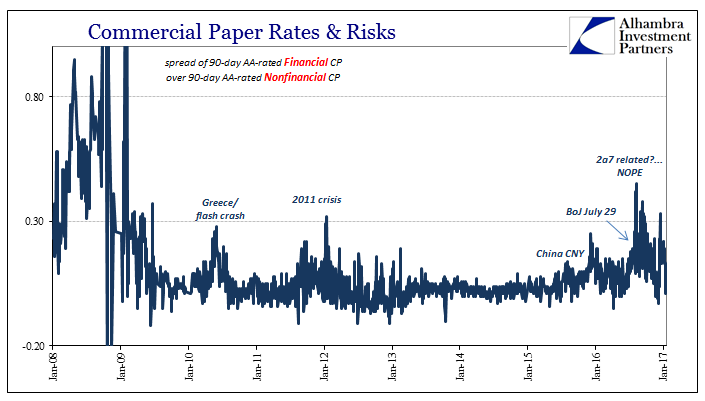

To that point, it is no longer fashionable to mention commercial paper given that money market reform is now more than three months in the past and nothing is different. That doesn’t mean there is no value in checking commercial paper, just not in the way others attempted in order to excuse all this. In fact, the view from commercial paper largely confirms the analysis of liquidity risk, and more than that its financial nature.

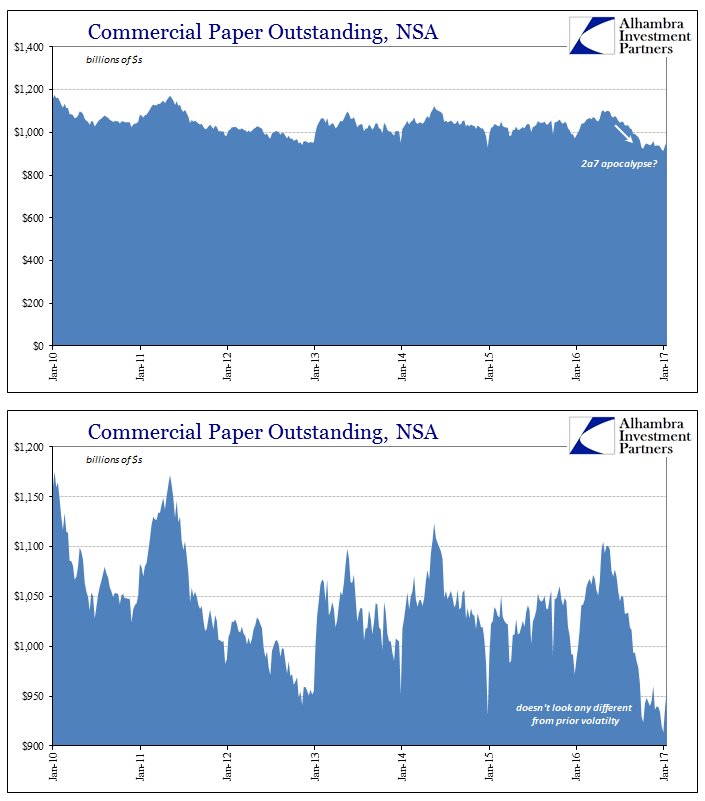

Commercial paper volume was down due to 2a7, but nothing so far out of the ordinary that it would explain LIBOR or T-bills (or, more specifically, LIBOR minus T-bills). Instead, however, the spread on published financial commercial paper rates continues to be unusually volatile and high – just like the TED spread.

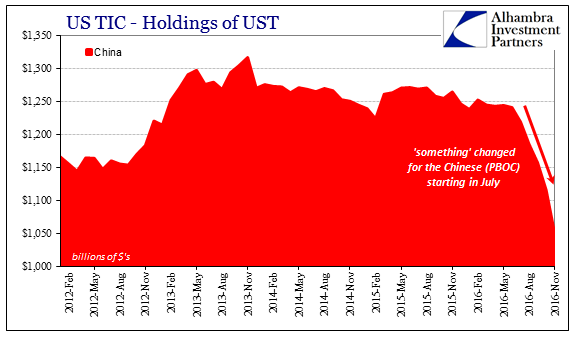

Given equivalent ratings, there is no other reason apart from financial risk that financial issuers would be required to pay more to issue the same maturity paper. What’s most compelling is that volatility in this spread dates back to China and CNY in August 2015. That was, of course, the same moment that the TED spread started to behave in exactly the same way, and the PBOC falling into RMB overdrive.

If the PBOC is increasingly desperate in RMB terms due exclusively to its “dollar” terms, we should be able to corroborate that view in “dollar” conditions – like we just did.

Stay In Touch