Ever since the panic in 2008, the string(s) of events that made up that crisis have undergone tremendous scrutiny and for good reason. Proving, however, that the amount of attention paid to a specific occurrence doesn’t necessarily increase the chances of understanding it, a great deal of what went on then remains a jumble of confusion predicated on mistaken assumptions; assumptions that survived even though on the most basic level the panic itself demonstrated their use in error.

As such, there is far much less investigation surrounding the return of crisis in 2011. This is a huge mistake, as I would argue there is more relevant to our predicament in 2017 contained in 2011 than 2008; the crisis established the reversal, the re-crisis hammered in the final nail. A full part of the reason most analysis skips this period is that it is either lumped together with the original crisis itself, or, more likely, because it seems one of the few cut and dried moments of the last (lost) decade. First and foremost, the debt ceiling drama that led Standard & Poor’s to downgrade US debt establishes an easy connection, not the least of which in terms of timing. Second, the operational termination of QE2 accomplishes the same, where the last bonds were purchased under that specific program at the end of June 2011 and barely a month later there was great international struggle all over again.

Throughout that year, the outward behavior of monetary authorities in the US was as it always was – comforting, reassuring, and confident. The modern central bank operates in that way regardless of whether there is actually any reason for that projected mood. Based on Japan’s experience with QE in particular, where the FOMC had decided years before that admitting QE hadn’t achieved its goals was part of the reason it hadn’t in Japan achieved its goals (circular reasoning is a common occurrence in monetary Economics under rational expectations theory), therefore as a matter of established policy Federal Reserve officials were not going to do the same thing.

Internal discussion was a totally different matter. The recently released transcripts for the 2011 FOMC meetings show the contradiction very well, particularly during the showdowns of that summer. In 2008, by contrast, the Committee was either just plain confused or more often just plain wrong; in 2011, especially the two meetings in August, there was still confusion but far more honesty about it. An unscheduled conference call took place on August 1, 2011, followed in eight days by the regular policy meeting, and all that discussion contained within what looked so much like a mini-panic.

Thus, the discussions in 2011 parallel the transition or inflection in both the real economy as well as the monetary system. They established the baseline for how policymakers arrived, eventually, at their 2016 “surrender.” In other words, they had begun to ask the right questions that far back but had remained reluctant to embrace the possible answers to them until forced to by the events of the “rising dollar.”

There are two lines of inquiry contained within this analysis, one dealing more strictly with the economy, and the other money. This discussion will pertain to the former.

To reiterate, the dramatic reappearance of crisis had been dismissed even contemporarily by many in the mainstream as the mere act of the Fed no longer “printing money.” It does seem an easy connection to make, given, again, the close timing of the end of QE2 and the start of turmoil mere weeks later. That view, however, doesn’t factor a great many problems that had started to show up months before, while asset purchases were still being conducted. These were not just money problems (repo, FX) but more so economic in nature. As such, the Fed staff at the August 9, 2011, regular meeting attributed these sudden market fluctuations properly.

BRIAN SACK, MANAGER, SYSTEM OPEN MARKET ACCOUNT. I would actually like to argue that the declines on Monday were not entirely driven by the downgrade. I think they were a continuation of the decline in sentiment and the concerns about economic growth that we had already seen develop very intensely over the previous week. The downgrade did seem to add to those concerns. There could be several reasons for that. For example, one is that it just further reduces the chances of having a flexible fiscal policy response to economic weakness. And I do think that a lot of the pessimism about the outlook is partly related to this idea that there aren’t many policy tools to address the weakness in the economy. My point would be that the downgrade just added to that, but I think the primary driver of all this is really the revision to the economic outlook. [emphasis added]

This was, obviously, a major potential problem for markets as well as the FOMC, as Mr. Sack pointed out. The Fed had just concluded a second, very large round of quantitative easing and despite a hugely positive reception it didn’t actually appear very effective, if at all, where it was supposed to be – the economy.

DANIEL TARULLO, BOARD OF GOVERNORS. Despite the past year’s debate in which we’ve had different views, every member of this Committee is united in having been too optimistic. I think that the most pessimistic among us, of whom I was one, certainly did not expect that growth over the past four quarters would be only about 1.6 percent, and would not have thought so even if we had been told about the impact of Fukushima. Who among us today would stand behind the projections we made last year for GDP growth during this year—and particularly in the second half of this year? Almost none, if any, I suspect.

The public might be surprised at the candor expressed at this meeting, particularly as it stood in stark contrast to the public persona intentionally put on. In his address to the Jackson Hole gathering in later August 2011, Chairman Ben Bernanke started as he so often did by expressing the difficulties in the US and global economy, couching them as “risks” (which is not of itself improper). But, as was usual, his statement of those risks was followed by the assurances which received far more attention and, I suspect, lingered far longer in the imaginations of the media and public.

There have been some positive developments over the past few years, particularly when considered in the light of economic prospects as viewed at the depth of the crisis. Overall, the global economy has seen significant growth, led by the emerging-market economies. In the United States, a cyclical recovery, though a modest one by historical standards, is in its ninth quarter.

It may be a slow and plodding recovery but a recovery nonetheless. Contrast that with his market assessment made in private at the scheduled August 2011 FOMC meeting:

CHAIRMAN BERNANKE. I think instead that there are some important connections between what’s happening in the financial markets and what’s happening in the economy. First of all, financial markets are giving us information. They’re telling us that there has been a general darkening of mood and expectations about where the economy is going. Second, financial conditions themselves have real effects on the economy. Not just lower asset prices, but increased stress and reduced risk-taking will affect the ability of the economy to recover.

It is that last part which has become paramount only because it was paramount all along; Economists just didn’t want to face up to the possibility, though by 2011 in the growing questions about QE2, in particular, it was already to many critics an established fact. Thus, the crisis in 2011 was not to further raise these questions so much as to answer them. As I saw it, the mere fact of a second QE invalidated the intentions of the first, whereas in the aftermath of the second QE the FOMC finally began to consider the same possibility as more than random chance.

Some members of the FOMC were much further ahead than others. This is also not surprising as the Committee itself in whatever the actual membership through time always consists of only three or four who contribute, leaving the rest as empty suits clearly unmasked by the transcripts. Among those who fell in the former category was Governor Tarullo. He urged at one point during the discussions for the members break out of standard protocol and start facing the problem with some new thinking, or at least a base of honesty apart from, or even totally outside of, orthodox doctrine.

MR. TARULLO. After all, both the string of bad intermeeting data and the substantially reduced expectations, not to mention the recent declines in markets, suggest that the factual predicates for our policy dispositions during the past year were, to a greater or lesser extent, misplaced.

Now, the economic go-round in a typical FOMC meeting is a pretty formal, almost—and sometimes literally—scripted affair, and even the policy portion of most of our meetings tends to play out in a fairly structured fashion, and properly so, since proposed language and alternative policy options will quite sensibly have been proposed, modified, and much discussed before we convene. Today, I think, should be different. The cumulative effect of the gathering evidence of stagnation, the psychological impact of the ratings downgrade, the growing concerns that euro zone problems may not be contained, and the global market drama of the past couple of days has made this a potential inflection point.

I have rarely seen truer words ever expressed in one of these meetings, and I have examined hundreds upon hundreds of transcripts. He was arguing as a matter of both economy and policy how to address the idea of a more-than-temporary downturn as well as the growing possibility, as evidenced by the reflaring crisis, that monetary policy just might be helpless in the face of it to positively alter its trajectory. This was no usual policy meeting, made that way by crisis that was more than the usual (by then) crisis.

In that view, which was if not widely shared, at least, for once, admitted to the discussion, there could only be huge gaps in knowledge both of the operations of monetary policy as well as how they actually (rather than in theory) affected and might continue to affect the real economy. After all, Brian Sack felt it necessary to remark on several occasions, “I think it’s worth pointing out that this is all happening with $1.6 trillion of reserves in the system.” The incongruence of what happened in 2011 and everything that followed thereafter is contained in that one simple declarative clause – the Fed had “printed” $1.6 trillion but surely nothing was acting like it.

Staff Economist David Wilcox came right out and said it:

MR. WILCOX. We’ve been marching determinedly in a negative direction. John Stevens had a nice exhibit in yesterday’s Board briefing that showed just how much we’d taken the forecast down over the course of this year. Also, I want to just emphasize that I think the gaps in our understanding of the interactions between the financial sector and the real sector are profound, and they have, over the past few years, deeply affected our ability to anticipate how the real economy would respond, and they are continuing to do so now. This is an ignorance that we share with the entire rest of the profession, and I think one thing that is good to see is the enormous amount of work that’s going on at the Board, in the System, and in the profession at large in an attempt to develop a better understanding of the interactions between the real sector and the financial sector, operating in both directions. But boy, I don’t know whether that literature is in its infancy, but I would not put it at any more beyond toddlerhood. We’ve got just an enormous amount yet to learn and incorporate in that regard. [emphasis added]

In short, they really don’t know what they are doing. What happened, then, between the great questions asked in 2011 and Janet Yellen finally in October 2016 admitting publicly the depressing answers was something like an official benefit of the doubt. The sentiment that prevailed after the August 2011 meetings right into 2012 and the introduction of QE3 (and 4) was delivered by James Bullard, St. Louis Fed President.

MR BULLARD. I also disagree with the Chairman on the QE3. I do not think we will be able to avoid a discussion of QE3 going forward, as much as many of us may like to. This is our most potent weapon, and it’s more promising as having effects on the economy—and we can debate what those effects are—than any of the other tools in our toolbox. This is because the QE program influences inflation expectations and therefore has potential to drive real interest rates lower if that is what the Committee desires.

The FOMC was just not ready at that time to give up on QE because QE was the genius idea; it was, as Bernanke had described back in his November 2002 “deflation” speech, the very power of the Federal Reserve itself, the power of any and all central banks. To conclude in 2011 that it wasn’t as powerful as they had dreamed was just too much for many of them to rationally consider – though, as Tarullo and Wilcox implied, they really should have. The implications are now clearly seen in wasted years more than wasted economy.

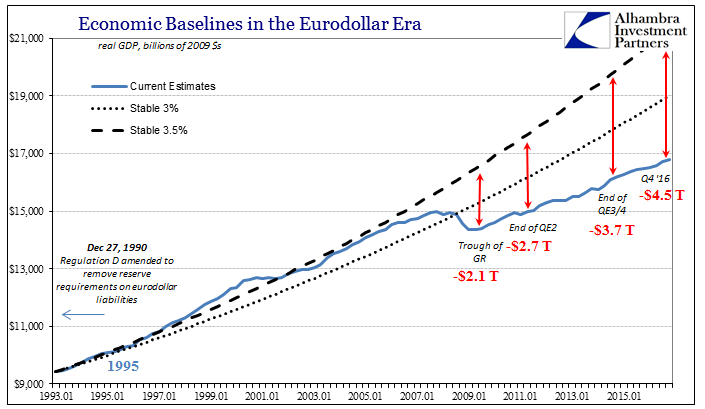

Thus, we can better appreciate why policymakers were so ready to blindly embrace the economy of 2013 and especially 2014 despite all the lingering, unsolved problems attached to it. As I wrote Friday with regard to yet another dispiriting but not unexpected GDP report, they really, really wanted to show that they did know what they were doing after all. In especially the unemployment rate it was tantalizingly within reach, for a time. Once the “rising dollar” fully intruded, however, officials had their answers to the 2011 questions left to them in no uncertain terms.

The crisis in 2011 should have been the final call to action, for actual monetary reform, rather than to start the debate over the same topics as 2008 in a different setting. Because there was no fear of failure, the global economy would surrender so much more lost opportunity and economy while policymakers patiently waited out the overwhelming confirmation that, once again, they really don’t know what they are doing.

Stay In Touch