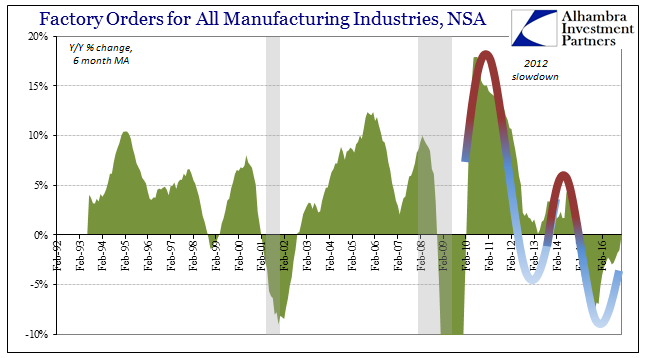

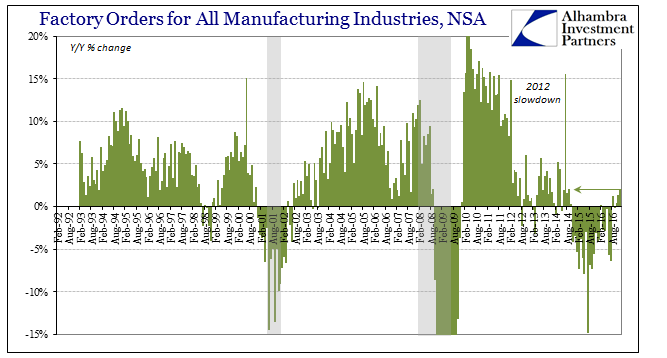

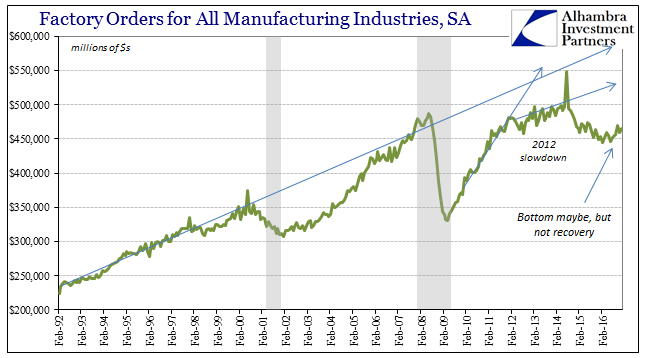

Factory orders rose 2.0% in December 2016 year-over-year (NSA), the fourth positive number in the last five months. In what is a perfect commentary on the sorrowful state of the economy, it was highest growth rate since September 2014. It seems increasingly likely that the manufacturing recession attached to the “rising dollar”, the one that created a near-recession for the whole economy, has ended. The seasonally-adjusted figures show February 2016 as the lowest point, which makes sense given the timing of all the factors that went into creating and manifesting the downturn.

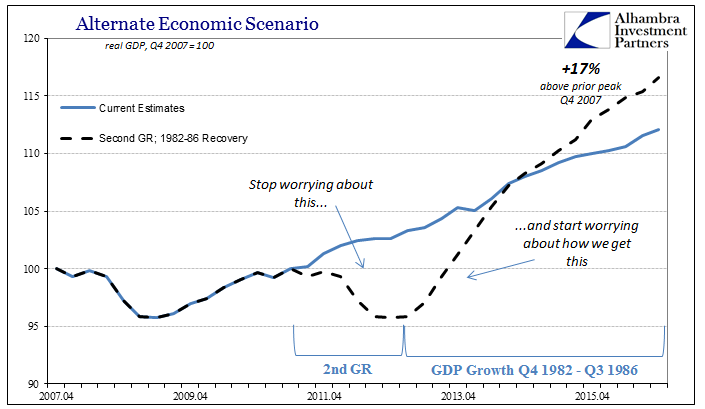

The problem, as always, is that having passed beyond that specific condition there is as yet any evidence that the economy is experiencing anything more than its absence. In other words, being away from near-recession isn’t the same as being on to actual growth. In that respect, what we see now appears to be far too much like 2013 and early 2014, a repeating in the depression cycle that also makes perfect sense.

The worst of “global turmoil” in late 2015 up until February 11, 2016, was about the acute interruption of global “dollar” flow which has immediate and direct impacts upon the real economy – especially in terms of goods and the manufacture of goods, both of which require constant monetary and financial resources. The cessation of the immediate threat (in terms of risk) allows some activity to resume that was delayed by the disruption. Some of that activity, however, never comes back, which is the truly insidious nature of the “dollar” depression. Like a noose, the economy is only ever slowly strangled.

In the immediate aftermath of the Great “Recession”, factory orders never hit anything like 2%; they went from -3.70% in November 2009 to +0.50% that December and then +13.40% to start off in January 2010. Even in the aftermath of the 2012 slowdown in early 2013, factory orders rebounded somewhat more convincingly, from -3.2% in March 2013 to +1.4% in April and 3.6% in May. Though orders have been mostly positive these past few months, there is just no acceleration; in order, +1.2%, -0.1%, +0.4%, +1.3%, +2.0%.

To start 2017, the US factory sector has both the overall slowdown as well as the more than 2-year contraction of the “rising dollar” to contend with and overcome. Momentum is a serious part of growth (which is why economists talk a lot about hysteresis) and it’s been five years since any can have been claimed.

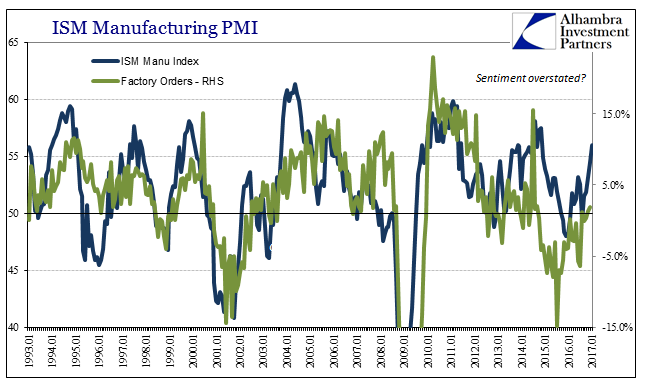

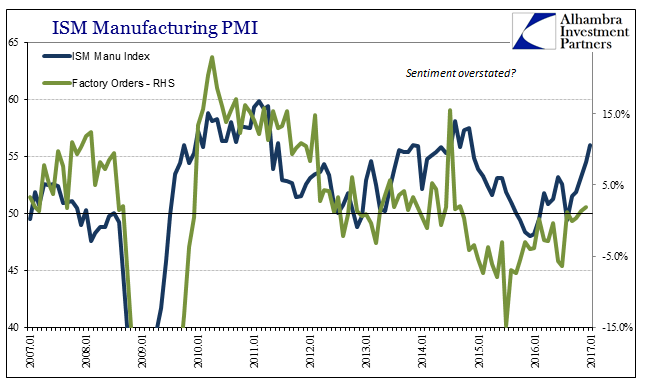

Sentiment, however, has tended to ignore this overall context, though that is in many ways by design. A typical PMI survey, for example, only asks if your business is getting better or worse, it never asks you by how much to either side. It is difficult to distinguish between 50% of respondents saying business is 1% more than before (all else equal) and 25% of them saying business is 10% better.

The relationship between the ISM Manufacturing PMI and durable goods is significantly better, as noted earlier this week, but there is still the same outline of a correlation with factory orders. Since 2012, the same divergence found with durable goods orders is detected via factory orders (which combines orders of durable goods with those of non-durable goods).

The relationship between the ISM Manufacturing PMI and durable goods is significantly better, as noted earlier this week, but there is still the same outline of a correlation with factory orders. Since 2012, the same divergence found with durable goods orders is detected via factory orders (which combines orders of durable goods with those of non-durable goods).

There is a basis for rising sentiment, but only in the narrowest sense that, once again, conditions in the manufacturing economy are no longer getting worse. Absence of recession is not evidence of recovery, however. In this economy, the one that began in 2007, it is the worst case as it suggests another cycle of repetition – 2016 as 2013 or 2010; 2017 as 2014 or 2011. The only catch, and it is an important one, is that the economy is reducing down each time. As I wrote at the end of last year:

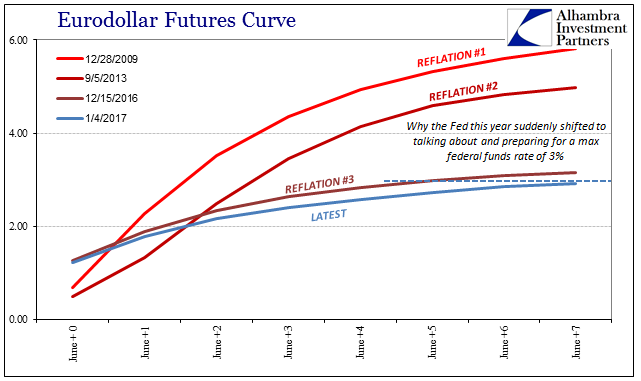

In technical analysis of the stock market, the idea of higher highs and higher lows is important as confirming conviction in the direction. The same is true of the converse, of lower highs and lower lows. In many ways the eurodollar futures curve has traded in just that latter trend, with lower reflation “highs” and lower flattest “lows.”

Indeed, all financial curves have behaved the same way. And like manufacturing sentiment, they share the same economic basis, though where at least the eurodollar futures curve is more aligned with that reductive economic trend than not. The economy is getting better (short run) but it really is getting worse (long run).

The problem with that is as also 2014 (or 2011), where with more positive numbers and even more steady positive numbers “we” get lulled back into the false sense of growth all over again. The public was completely forgiven for thinking back then that QE had actually worked, because without the further understanding and context that is always omitted it certainly seemed that way if for a short time.

This is where standard tools of analysis fall far short. What’s important is not the plus sign in front of the year-over-year factory orders estimate, the extent of this contraction is assessed in terms of time, a cost that only grows no matter plus or minus.

Stay In Touch