On February 8, 2007, exactly one decade ago today, shares of New Century Financial, a former darling of not just Wall Street but the mainstream, plunged 37% in panicky trading. The day before, February 7, New Century reported expectations for loan production for 2007 to be 20% below 2006 levels. But the real bombshell was the reasoning for that guidance, as the company reported that early-payment defaults and loan repurchases had forced it to tighten up its underwriting guidelines.

There were a number of occasions where famous last words were spoken during this period, but one analyst from Jefferies & Co. perhaps kicked off the trend, writing in response to the New Century revelations:

While we acknowledge this has the hallmarks of a ‘downgrade at the bottom,’ we believe it is better to acknowledge our mistakes than compound a bad stock call with stubbornness.

It was nothing like a bottom for New Century, of course, or, as it turned out, the whole global economy. Just a year earlier, the company had become the second leading originator in subprime mortgages, a distinction that today elicits a far different response than the one it did at the time it was attained. Then, subprime was a place to be and everyone wanted to be there. Traditionally, the story is told from the perspective of the Fed’s “loosening” of the “money supply” in response to the dot-com recession and more so the stubborn lack of recovery thereafter.

The history of New Century Financial, however, is one that defies this characterization of history. It had already been added to the NASDAQ 100 in 2002 and by 2004 had originated a stunning $42.2 billion in total mortgages, most of which were subprime but not all (Alt-A and other classes were welcomed). These didn’t happen because the federal funds rate was targeted to 1% in June 2003.

In hindsight, the story of New Century and the rest of subprime is patently ridiculous. But it shouldn’t have been left to hindsight, especially the unraveling of it all. The Fed, with all its mythical powers and abilities, did nothing for a full year while the system first doubted itself and then realized nothing was as it seemed – including the role of the central bank. As I wrote last week:

The fatal flaw that was considered in 2007 (rather than LTCM 1997) but proven beyond doubt in 2011 was that so long as whatever bank liability any eurodollar bank might create was considered currency, further balance sheet expansion would thus create all the “dollars” necessary to fund it. Thus, that fatal flaw was its circular reasoning, that balance sheet expansion created “dollars” which funded balance sheet expansion, creating more “dollars” and so on. Remove the expansion and the inconsistencies, risk primarily, implode the whole intent. Like a spinning top, it can only ever be stable at high rates of growth, because when it slows everyone starts to question whether that math-as-money is actually real or merely, like alchemy or the Nigerian scam, an impossible dream.

In other words, it was never truly about subprime except as a symptom of a larger distortion. In one of the great ironies of it all, the Federal Reserve last collected data for M3 for the week of March 13, 2006, not even a year before all this came to a head. The statistic itself was flawed, but the Fed responded to those flaws and incompletions with ignorance and dismissal rather than determined curiosity to go further and explore these new and confounding spaces.

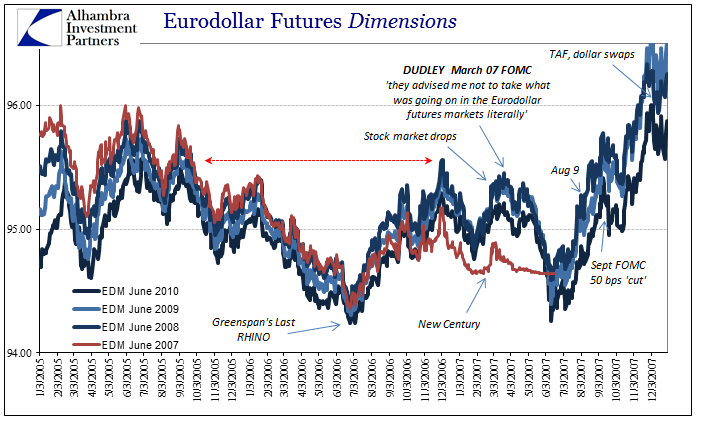

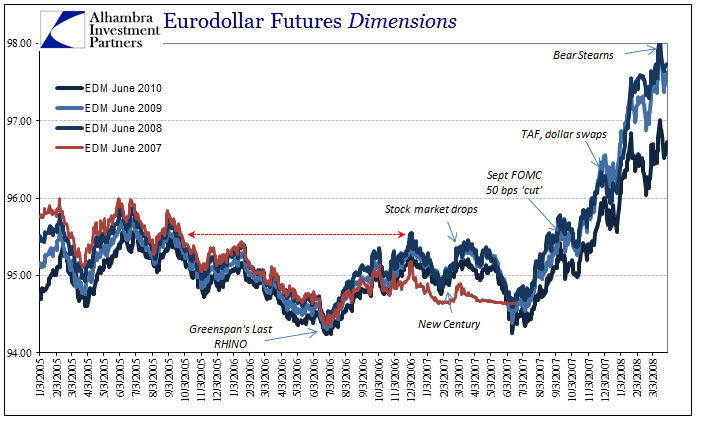

That was left to the market to do first, and bring the FOMC along for the ride as almost purely a spectator. From nearly the moment of Alan Greenpan’s final RHINO, the eurodollar futures market began to trade differently than the FOMC felt it “should” have. Eurodollar futures were suggesting future “rate cuts” because of some stuff inside the shadows of Wall Street balance sheet arcana that nobody actually cared about until February 8, 2007.

The ABX BBB spread, the difference between CDS of the most liquid subprime tranches and the interest rate of equivalent maturity US Treasuries, had blown out from 250 bps in December 2006 to more than 800 bps by February 2007. As that occurred, the eurodollar futures curve inverted, as did the UST yield curve. But it was eurodollar futures that really bothered the FOMC, who should have been listening to it instead of engaging in their usual monetary sophistry.

From the transcripts of the March 2007 FOMC meeting:

MR. DUDLEY. In contrast, longer-term expectations have shifted more sharply, with a larger move toward easing. As shown in exhibit 13, the June 2008/June 2007 Eurodollar calendar spread is now inverted by about 60 basis points. This calendar spread is more inverted than it was at the time of the December 2006 FOMC meeting…

An investor with speculative risk positions that would be vulnerable to economic weakness might hedge these risks by buying Eurodollar futures contracts. This hedging could push the implied yields on Eurodollar futures contracts lower than what would be consistent with an unbiased forecast of the likely path of the federal funds rate. [emphasis added]

In other words, traders were, in his view, overreacting on emotion as compared to what the Fed clearly was not going to do by moving off its neutral policy stance where the federal funds rate was at 5.25%. Central bankers often claim the mantle as champions of capitalism and markets, but if you actually listen to them it is perfectly clear that they are not. More often they despise markets as the opposite of how they see themselves, as objective and principled guides to the “greater good.” Markets stand in the way of their aims. In one specific instance among many illustrating this belief, Open Market Desk Manager Bill Dudley even invoked economists, telling the voting members:

MR. DUDLEY. Well, another explanation is that the economists who make the dealer forecasts are not the traders who execute the Eurodollar futures positions. So that’s a possible alternative explanation. Generally, there’s a disequilibrium. A number of people that I’ve talked to in the markets have said that this is what they thought was going on, and they advised me not to take what was going on in the Eurodollar futures markets literally because they felt that some of them were putting on these positions in case of a bad scenario that led to significant reductions in shortterm interest rates. So I’m basically taking the explanation somewhat on the advice of market participants who told me that they were doing this. [emphasis added]

Yes, by all means just ignore the most liquid market in the world because it is inconvenient for economists’ forecasts, and often the very same ones at the very same banks where traders were hedging for something really bad about the whole monetary system and the implications for it. Economists have nothing riding on the outcome of their forecasts, while the traders as agents for these banks had everything (literally, for some) staked to it. New Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke actually put his finger on this very clear divergence:

CHAIRMAN BERNANKE. I had been puzzled about the quantitative relationship between the subprime problems and the stock market. I think that the actual money at risk is on the order of $50 billion from defaults on subprimes, which is very small compared with the capitalization of the stock market. It looks as though a lot of the problem is coming from bad underwriting as opposed to some fundamentals in the economy. So I guess I’m a bit puzzled about whether it’s a signal about fundamentals or how it’s linked to the stock market.

He was puzzled quite a lot throughout his tenure, which explains quite a lot about his tenure. It wasn’t either bad underwriting or bad fundamentals, but rather both because of a single unifying element that the eurodollar futures market first saw coming. Bernanke as was commonly believe at the time, and still to some extent today, thought the Fed set monetary policy which set the conditions for the economy. Like entropy, monetary causation radiates out from the Marriner Eccles building. Most markets believed that was the arrangement, too. Starting in 2006, however, the growing sense was that “something” else set monetary policy and therefore the economy, as the Fed was merely, again, a spectator.

The last ten years have been about this very trajectory, one that until New Century (as well as HSBC, who on the same day announced growing losses from subprime, giving it all great significance as the largest bank/dealer to do so at that point) had remained completely in the shadows. February 8, 2007, was the day the lights started turning on about what it was that was actually going on in those darkened placed.

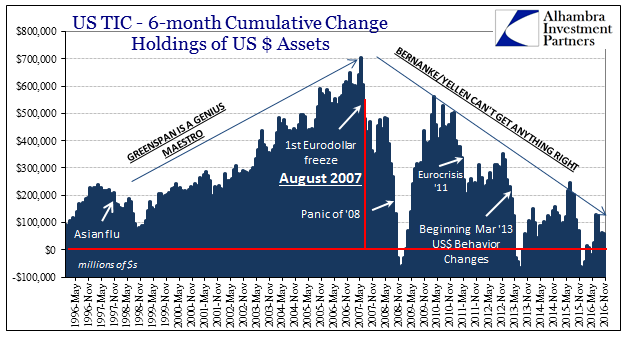

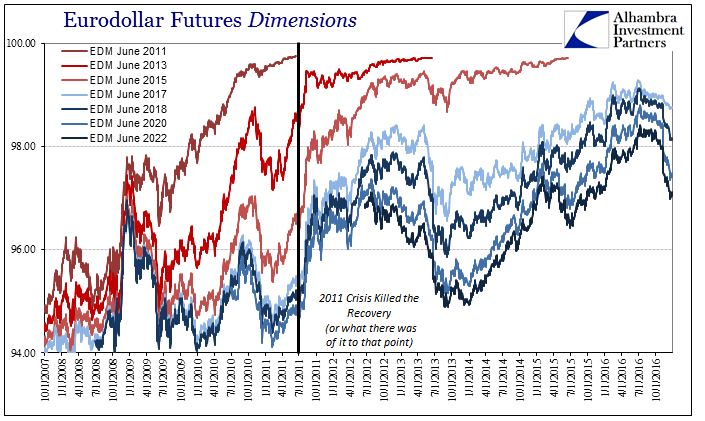

What started in 2007 was repeated in 2011, leaving the Fed completely helpless by then on the sidelines pitching QE’s that these same markets had come to barely notice (aside from brief “reflation” contemplations). Despite this rejection, there is still far too much enduring in the shadows (which is why things like 2a7 money market reform can be used conveniently to excuse bad acts and potential, and then simply forgotten when it turns out to never have been 2a7).

The name of that one forgotten firm is and has been utterly significant in a way that perhaps nobody could have imagined. Ever since subprime announced the downfall of the eurodollar to the world ten years ago, at first as just a possibility, it has indeed been a new century. Unfortunately, it has been one that we can only hope and wish will not last much longer than a tenth of one. So long as policymakers and officials are allowed to wander themselves in the dark, we are constantly reminded that it just might.

Stay In Touch