Economists have always fashioned themselves in the style of physicists. They endlessly scrawl incomprehensible equations on blackboards because it is the epitome of science, the allure of great intelligence seemingly to do great things. But where physicists have continued to describe and solve some of the world’s great mysteries, Economists only bungle. They described free trade from among the myriad of regressions, for example, as an unqualified good only to see a global revolt forming on that basis alone.

Perhaps the difference lies in the respect each discipline displays for what are actual limits to mathematics. Physicists show a healthy regard for those constraints while Economists do not. The former worry a great deal about what their math might not be recounting; the latter truly believe there isn’t anything worth knowing not already calculated in theirs.

Positive Economics has been a disaster because it assumes that knowing just a little can yield big and predictable results. The monetary system has been left as one such black hole in the intellectual designs of econometrics. And it is an ironic condition since it has been central bankers who have been at the forefront of the intentional ignorance. Central banks are, by their definitions, about money, and therefore everyone assumes central bankers must be the preeminent experts on the subject. In truth, they know less than you do because they rely exclusively on statistical regressions that take a decade of failure before they realize they don’t work.

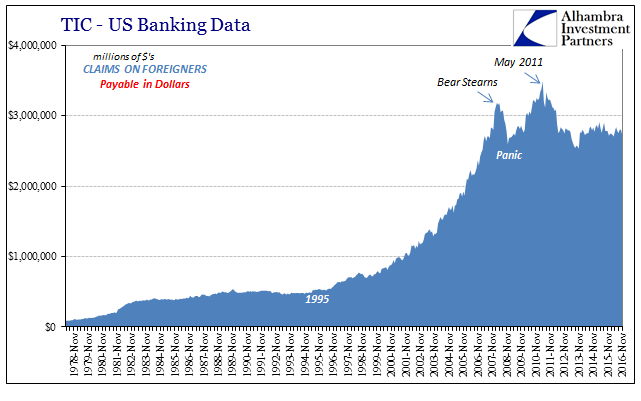

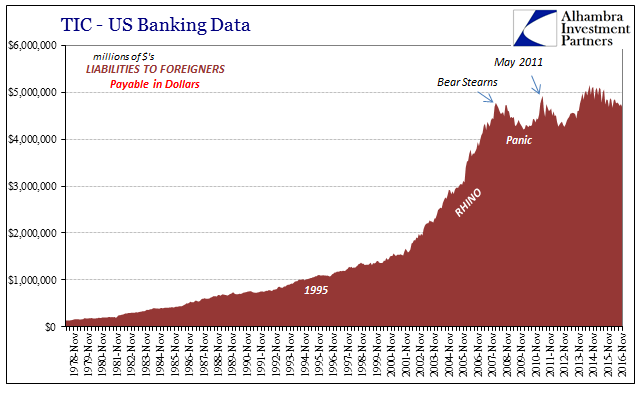

As I wrote earlier today, what’s missing from the eurodollar system is banks. This is an enormous problem for a credit-based currency regime, one that can never be solved by QE’s simply because banks perform all sorts of money dealing functions that QE could not nor will ever address. To actually get at this global money problem requires venturing into what it is that banks are supposed to do but no longer want to. We have to more fully understand how global eurodollar banks actually operate and do so in open monetary terms.

That’s a big problem because nobody really knows what goes on in them. Bank balance sheet capacity is the central pillar for the whole thing, but as difficult as it is to describe it is impossible to observe because on an individual level it is black box. Thus, we can observe the effects of balance sheet capacity as well as its further absence even though we can never see it in a primary sense. It truly is like trying to define a black hole, and working backward to do it.

What makes a black hole black is its event horizon, meaning that there is a specific point in space past which light is no longer able to escape. Beyond the event horizon nobody really knows what is going on in the black hole itself. Since it cannot be observed, math has been constructed to “see” it for us, but the laws of math and physics seem to break down. Physicists have spent their whole careers trying to figure out what is down there, convinced many of the great answers to the entire universe and the keys to it might be lurking past that point.

Bank regulations are focused on describing to the public what is and is not a “good” bank. The entire Basel regime relies upon mathematical calculations to achieve this single goal largely because the evolution of money left regulators so far behind the curve on the liability side. And yet, the flaws with Basel are never described as flaws with Basel, they are instead relayed as difficulties in executing what is otherwise a good idea. The events surrounding 2008, for example, should have put to rest any notions that regulatory regimes can ever be up to the task of describing for us what is a “good” bank; and by extension what is monetary.

The alternative to that standard is for regulations to instead allow us to decide for ourselves what constitutes a “good” bank. That would mean letting the public go past the balance sheet event horizon and right into all the places that are right now still off limits. In other words, a return to market discipline and individual analysis.

A long time ago authorities decided that the people could no longer be trusted with that task. They would be too susceptible to emotion and interference, unable to distinguish fact from rumor. The 1929 crash was used endlessly to justify this distrust of both free markets and the freedom they provide the public. Economists reasoned that there must be dispassionate experts who would stand between wild unpredictability and calamity, to perform the function of objective monetary arbiter. It didn’t exactly work out that way in 2008, where capital ratios were totally set aside because they were not just unhelpful but in many cases misleading.

The switch to Basel actually shows the illogic of it. The primary reason regulations swapped liabilities for assets was, again, because regulators couldn’t understand what was going on in bank balance sheets, the money side. Basel wasn’t a foolproof scheme to objectively sort “good” banks from bad, it was instead a copout, a poorly designed short cut. They couldn’t keep up with banks in the changing nature of money so they sold it to the public they just didn’t need to. At this point it is worth reminding that banks were overwhelmingly in favor of this.

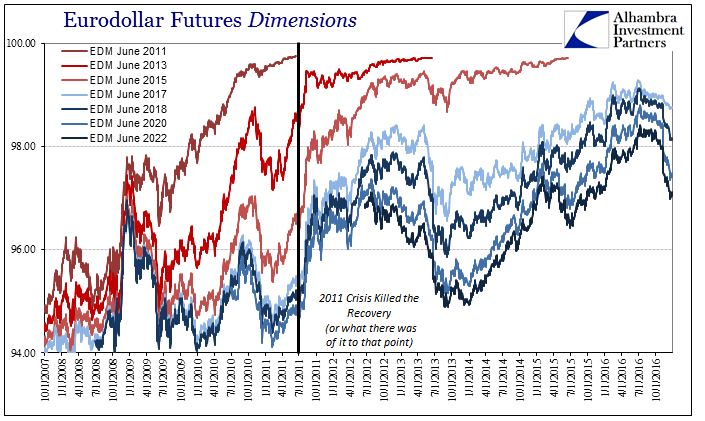

If regulations were turned around again to provide for market discipline meaning dispersed judgment, then banks would have to be far more open about what they do and why. Into that process we might then be able to pinpoint the cause, for example, of the “rising dollar” before it ever starts to rise. Money might again become more predictable rather than less so with authorities increasingly uninterested as to why that has been. We might be able to see that it has been volatility and modeled future volatility that has been behind the withdrawal of bank capacity especially since 2011; or if not, what was instead. We simply should not have to guess, no matter how reasonable and reasoned. Knowledge is power, and from power springs accountability.

Beyond the event horizon as it relates to the eurodollar decay is surely VaR, vega, and how those have affected balance sheet construction and capacity once QE was proven to be a lie.

It wasn’t Dodd-Frank or Basel III that put turmoil upon the repo and FX markets then, it was instead the combined Oh Sh## moment where banks realized they were still holding massive prior risks without the expected recovery by which to deal with them. What happens if you expect to repair your balance sheet with retained future earnings only to find that isn’t so easy and guaranteed as you thought given that money printing turns out to have been “money printing?” You shrink. Period. The faster the better. The more that condition extends, the more you shrink.

What Basel and Dodd-Frank did do is prevent the rest of the world from realizing this was happening. Banks rejected QE, but from the outside it was given legitimacy in monetary terms it never deserved. The world kept expecting recovery when one was never possible. I happen to believe that the regulatory regime in place should rather concern itself as to how that could ever happen.

All the data shows that is exactly what occurred; the recovery died in 2011 but the death was covered up by government functions that are supposed to be on our side. We need to know exactly what’s on bank balance sheets (and more than that what isn’t) and why, and that should be the focus of the next regulatory regime. Sticking with Basel is sticking with the same top-down system which continued to proclaim all banks as good and because of that recovery was certain. It helps obscure what desperately needs to be fully and completely illuminated. The only thing regulators should be doing is assuring full transparency, because not only do we really need it but also because their judgment and math has proven such an indescribably poor substitute for it.

Stay In Touch