The hedge fund industry is not quite dead yet, meaning that it can still cause a great deal of disruption before it expires. It is here where things like rehypothecation and the bastardization of prime brokerage functions were perfected, such that we might use that term in this manner. Despite so much outward attention paid in this direction, very little has been actually learned about how it all fits within the overall systemic capacity issue.

Most of the emphasis appears to be pointed on the pro-cyclicality of hedge funds, particularly with regard to stocks. In any selloff people sell, a tautology of course but in the case of hedge funds there are further liquidity dimensions that might amplify the selling. In other words, the way hedge funds are structured they end up being top-heavy during more dramatic market events, having to factor not just pricing or current liquidity but also future liquidity should the fund be hit with a run by its own investors. In addition, there is the more obvious effect of leveraged vehicles being subject to marginal and collateral calls (where the real interest should be tuned). It can all turn self-reinforcing very quickly and with no realistic “off” switch.

It is somewhat perplexing but only given that hedge funds had become a tremendous source of market liquidity (stocks) on the way up. In other words, it is reasonable to ask whether there might be some asymmetry as they pull back (and what might replace them in that role). There aren’t any good answers as yet, apart from the usual corporate repurchases as well as foreign central banks. That may be why the seemingly unstoppable stock market actually got pulled into 2015-16.

While everything appears to be going right once more in stocks, there are any number of cautionary indications underneath “reflation”; starting with how “reflation” is just an idea at this point, not one particularly well defined. In specific terms of market liquidity and hedge funds, you would think “reflation” would be a point of reversal to a healthier systemic stance. It doesn’t appear to be the case:

Using an analysis that turns mainly on how much volume is occurring in stocks favored by professional speculators, Novus says liquidity is at an all-time low.

The methodology this specific firm uses with which to make such a determination is unclear, but it is related in part to how crowded a great many stock issues have become.

As money flocks to popular names, the window of escape gets smaller. Novus, which sells products aimed at avoiding liquidity traps and managing risks, theorizes that it’s no coincidence that in each of the last three years, the low point of liquidity all came within three months of a market selloff. Last time it was as low as it is now in July 2015, the S&P 500 suffered the worst decline in four years the next month.

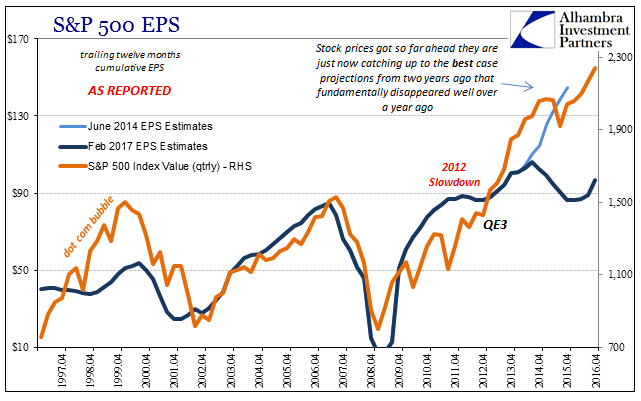

As ZeroHedge further points out, the NASDAQ 100 is now more overbought than at any time since the height of the dot-com bubble. There is an almost palpable incongruity to it all that perhaps aids in obscuring these massive imbalances; in the late 1990’s, there was at least a feeling of a real economic basis for the dot-com bubble; in the later 2010’s, what would we even call it? I noted earlier the disparity between earnings and stock prices, suggesting that at best the current bubble would be the Depression Bubble. Because that on its face sounds ridiculous and preposterous, it may not be taken seriously enough. In the late 1990’s, it was clear exuberance where good times just got out of hand; how can a bubble be exuberant during a period when almost everyone is a pessimist?

It’s another element of asymmetrical risk that “everyone” thinks is in their favor but really is not. The “reflation” after QE3 was thought to be a “can’t miss” in the market, but was proved by the “rising dollar” to be quite risky after all because it was fundamentally unfounded. Economy is not the market, of course, but even still factors and parameters like hedge fund liquidity did matter and likely still do.

Nothing has changed, including liquidity, but the market acts as if everything has and for the better. Maybe it all will at some point, but at least the risk of undercounting (again) these parameters is as high as ever.

Stay In Touch