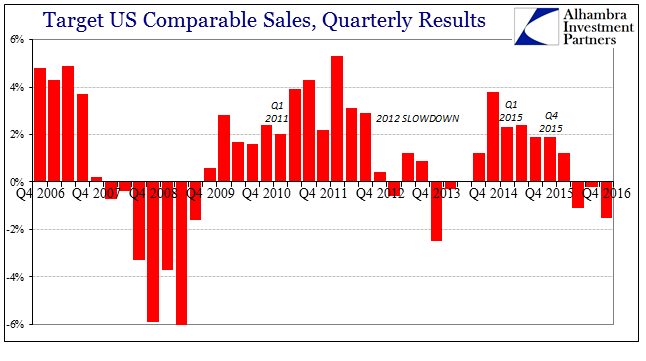

Target announced both bad results as well as distressing guidance. The retail giant has been under pressure, and its quarterly update for its Q4 only confirmed the concerns. The company first reported the worst comparable store sales numbers (-1.5%) in three years. It was the third straight quarterly contraction for its comparables. For stores open at least a year, same store sales were down a sharper 3.3%.

The outlook is for no better, where management predicts a “low to mid single digit decline” for its Q1, and then low negative single digit comps for all of 2017. These results have triggered what Target is claiming will be a transition to a new model, one that will present “headwinds” for the rest of this year and perhaps some undetermined time beyond. CEO Brian Cornell promised more details in the coming days.

It should be noted that while Target struggles its rival Wal-Mart has fared better. There could be a couple of contributing factors, including a boycott launched in the middle of last year related to Target’s bathroom policy (I am only pointing out the coincidence of it). Since the company’s sales turned negative just as that started, it is a possibility that needs to at least be considered with Target as a further anecdote.

The company’s management, however, clearly does not believe that is the case at all. Instead, Mr. Cornell cited what has become the familiar refrain of consumer transition:

Our fourth quarter results reflect the impact of rapidly-changing consumer behavior, which drove very strong digital growth but unexpected softness in our stores.

This is, of course, a trend already clearly defined in broader data such as retail sales. What is at issue, and what may be of use from Target’s data, is the possible driving factor behind “rapidly-changing” consumers. There is the possibility of simple randomness, a sort of unseen, unknowable tipping point for where online shopping almost all-at-once became the dominant trend. I find that an unlikely case.

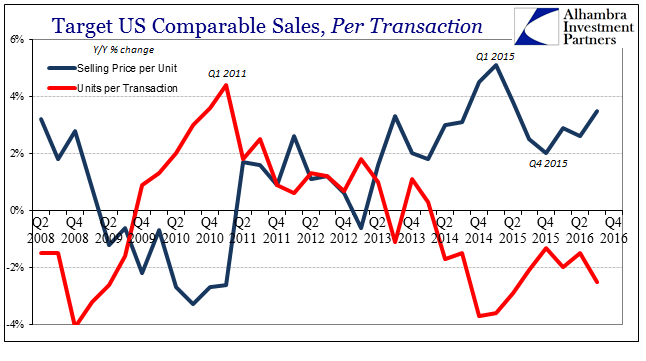

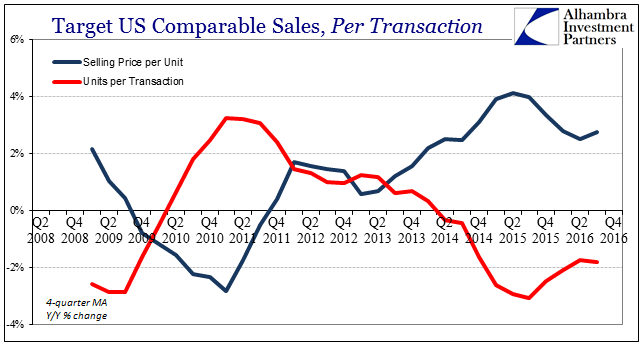

Instead, Target’s quarterly detail includes transaction level data that points in the direction of something else. Comparable sales are the product of the number of transactions in each store as well as the average amount spent on each transaction. The latter is further broken down by the average price of each transaction as well as the number of items in it.

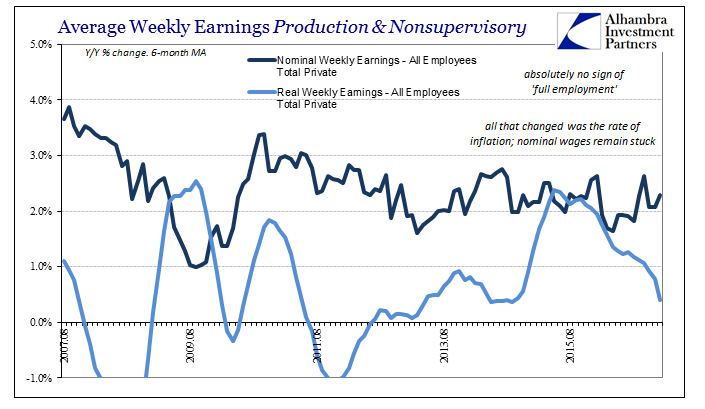

The data provided by Target shows an unmistakable inverse relationship (the 4-quarter average of these variables, below, is perfectly clear) between the average unit price and the number of items a customer will buy during a single transaction. While the relationship could be defined by several factors, it is quite reasonable to submit that lack of wage growth would be perhaps the defining variable. In other words, as the average price rises “too much” it forces consumers (at least at Target) to buy fewer items in a single purchase, a limitation that is very familiar to anyone on a discretionary budget that doesn’t expand.

What these transaction figures show is in all likelihood a high degree of price sensitivity from among Target’s wide customer base. It is not the conclusive factor always in Target’s on again/off again comparable store sales, but it appears to have been at key moments during the “recovery” period.

When average prices were at their lowest around the middle of 2010, before they would start to rise sharply, both the average number of items per transaction as well as a rise in the total number of transactions led Target comparable sales to stage what looked like an economic recovery. It ended in the middle of 2012 as prices and the number of items were more neutral, and thus leaving the number of transactions as the primary variable leading comparable sales lower again (a pure macro result for a pure macro period).

In 2014, as macro conditions improved (though not nearly as much as was heralded) price pressures began to resume. The decline of them in 2015 seems to have stabilized Target sales during that year even though macro conditions once again worsened. In 2016, by contrast, on the macro level there has been little if any improvement while price pressures have been resumed from their 2015 layoff. That appears to have left Target’s customers with the reverse condition as to 2010-11, and therefore Target sales to be declining.

This works as a proxy for not just Target’s sales and store data, as the rebound in oil and thus gasoline in tandem with the per transaction estimates would propose the same price sensitivity and budget constraints (again, absent wage and earnings growth). If you spend more on the same amount of gasoline, it makes shopping elsewhere that much more vulnerable.

Though it is just an anecdote, it is a compelling one given the structural shifts that all of a sudden accelerated sharply in 2016; the very same that Target’s management is alluding to and likely building toward with its coming change to its “financial model.” In other words, there is some detailed evidence here that consumers are fleeing “brick and mortar” retail as the combination of price sensitivity related to depressed macro factors like wages. They go to Amazon rather than Target in store even though they in all likelihood would prefer to shop in the real world, and all because they are forced to on limited discretionary budgets that are more and more limited.

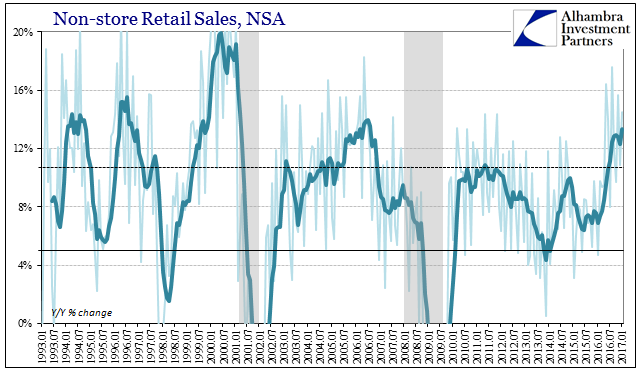

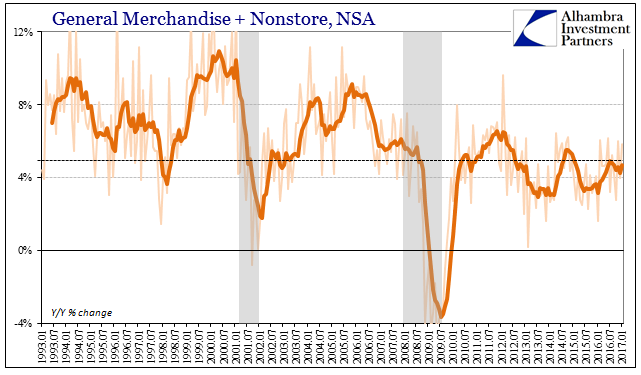

That would certainly explain why despite serious acceleration in Nonstore retail sales the combined sales of Nonstore plus General Merchandise, which includes Department Stores like Target, remain stuck at a very low level. People are very likely being driven to their smartphones by the lack of economic growth that in 2016 has combined with a partial rebound in consumer prices (especially oil).

It would further suggest, assuming this is all correct, why the whole idea of monetary policy to work through inflation expectations is simply insane (just ask Japan if more confirmation is needed). Inflation expectations are supposed to lead directly to wage gains, but even economists would concede, if forced to, that they don’t really know why they expect that to happen (Positive Economics). It’s all a matter of pure mathematics, correlations derived from very different time periods (like the 1970’s). It’s the difference between Economics and economics.

Target is, of course, far from the only retailer to be struggling right now even if its idiosyncrasies are at fault. Regardless if they are, the comparable store figures on the transaction level at least still suggest a high degree of price sensitivity, and therefore some possible (good) evidence of our ongoing predicament.

Stay In Touch