Why aren’t there more homes for sale? The lack of inventory continues to stifle the real estate market, but there aren’t any good reasons offered for what seems on the surface a bit of a paradox. The total volume of resales, according to the National Association of Realtors, was in the prior month (January 2017) the highest in more than a decade. That sounds good, but in reality it is less striking than it is made out to be and was more of an aberration than indicative of a healthy market. The volume of home sales fell sharply in February to a level more consistent with the past few years.

There is clearly something amiss, though almost every mainstream outlet is reluctant to state it. In fact, as I noted one year ago yesterday, it had become habit for the NAR’s chief economist Larry Yun to blame “unexpectedly” weak February’s on the weather rather than consider more forcefully the inventory side; he did this for February 2014, February 2015, and once more for last February. This year, their press release is thankfully devoid of snow and winter, but is instead left to incomplete lamentations about affordability.

Part of the problem in blaming winter those previous years was all the talk about wage and economic growth that was supposed to be unleashed long before now. That was the view of the unemployment rate, and one widely shared among economists and policymakers alike (who refused the clear, common sense counter interpretation of oil). By citing “affordability” rather than temperature, the NAR has apparently wised up – but not quite all the way.

A growing share of homeowners in NAR’s first quarter HOME survey said now is a good time to sell, but until an increase in listings actually occurs, home prices will continue to move hastily.

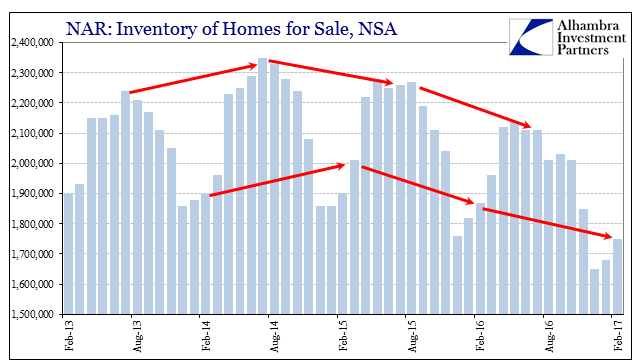

It may be too much parsing of what may actually be boilerplate sales language, but it still doesn’t actually square with the figures for inventory. People say it is a good time to sell, but the relative number of people who are actually doing so has drastically shrunk and for almost two years now.

As I wrote last year:

Two years later, inventory continues to decline. That has had the effect of squeezing prices higher and out of reach for far too many, leaving them to depend on the whims of the FOMC (and really the 10-year UST yield since monetary policy is almost irrelevant) for holding mortgage rates. This makes no sense under the conventional narrative, as rising prices and gaining economic momentum should lead to increasing inventory, or, at the very least, the level of unsold homes rising to match overall sales.

It suggests a dichotomy where so much positive feelings are very curiously unmatched by action; consumer confidence is, like the volume of resales in January, supposed to be at a high not seen in a decade and yet it doesn’t translate into activity in all the places where it really would and should (autos as well as houses).

It isn’t quite a world turned upside down but perhaps something close enough to it. We see similar divergences in places like the stock market, where at least there action meets perception but also on what amounts to a faulty premise (just look at EPS). In other words, there is a reluctance of emotion to accept that the US and global economy has followed toward Japanification, a low growth paradigm that is far different than many seem able to more completely comprehend (the Fed hiding this interpretation they now, belatedly, share and giving the public no favors by doing so).

Thus, consumers express high amounts of optimism because after a decade it just has to go right eventually, as they simply cannot believe the economy will stay down forever. And yet, they know “something” isn’t quite right, still, so while they say they are optimistic in these kinds of situations they sure don’t act on it. It’s more of a “wait and see” approach, which makes sense in contrast to something like stocks where the presumed downside of “wait and see” is minimal (shorter memories). After the general experience of the housing bubble, by contrast, many people have learned and further have retained the lessons of the downside of buying up in real estate no matter how good they really want to feel about Janet Yellen’s public take on the unemployment rate.

Despite what consumer confidence indices make out, there is a discrepancy that over the past few years is as compelling as it is consistent.

Stay In Touch