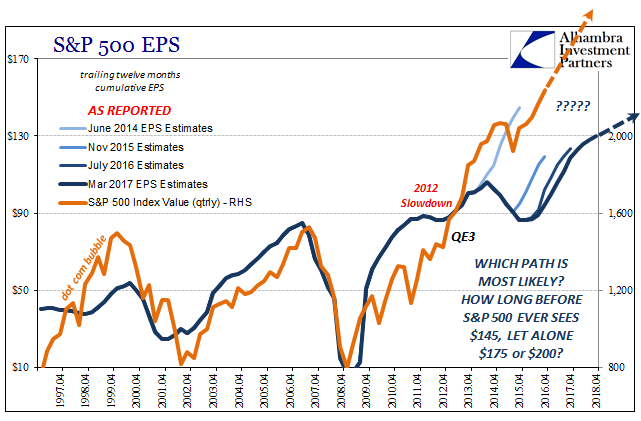

With nearly all of the S&P 500 companies having reported their Q4 numbers, we can safely claim that it was a very bad earnings season. It may seem incredulous to categorize the quarter that way given that EPS growth (as reported) was +29%, but even that rate tells us something significant about how there is, actually, a relationship between economy and at least corporate profits. Keynes famously said that we should never worry about the long run for there we will all be dead, but EPS has arrived at the long run and there is still quite a lot of living to do.

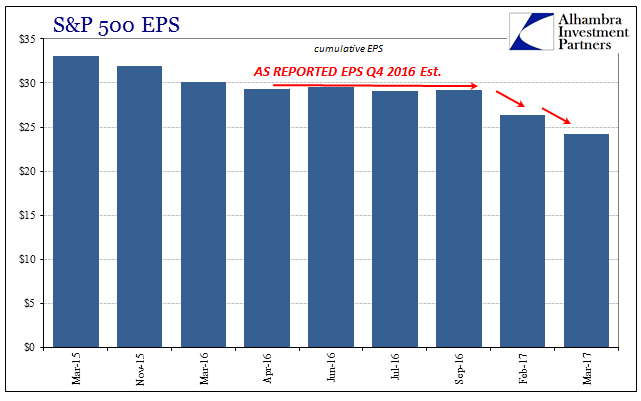

As late as October, analysts were projecting $29 in earnings for the S&P 500 in Q4 2016. As of the middle of the earnings reports last month, that estimate suddenly dropped to just $26.37. In the month since that time, with the almost all of the rest having now reported, the current figure is just $24.15 – a decline of over $2 in four weeks. Therefore, 29% growth is hugely disappointing because it wasn’t 55% growth as was projected when the quarter began.

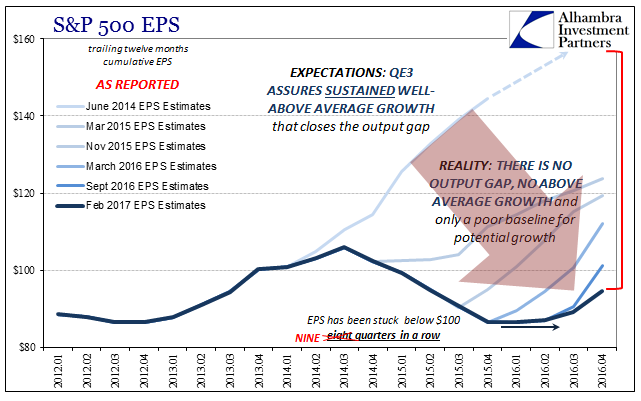

It is also the timing of the downgrades that is important as it relates to both “reflation” and the economy meant to support it. All throughout last year, in the aftermath of the near-recession to start 2016, EPS estimates for Q4 (and beyond) were very stable, unusually so given the recent past. That shows us how analysts, at least, were expecting the economy to go once it got past “global turmoil.” It was the “V” shaped rebound typical for past cyclical behavior.

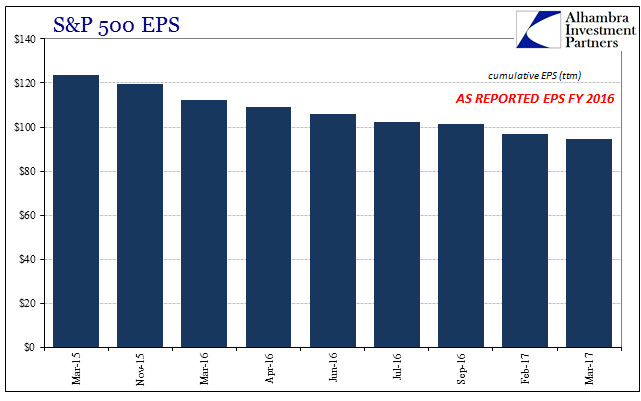

But it wasn’t until companies actually started reporting earnings that the belief was tested and then found severely lacking. With just $24.15 for Q4, total EPS was for the calendar year less than $95, the ninth straight quarter below the $100 level. More importantly, on a trailing-twelve month basis, EPS don’t appear to be in any hurry (except in future estimates) to revisit the prior peak of $106 all the way back in Q3 2014.

As noted last month, that means a great deal of consistency between earnings and economy.

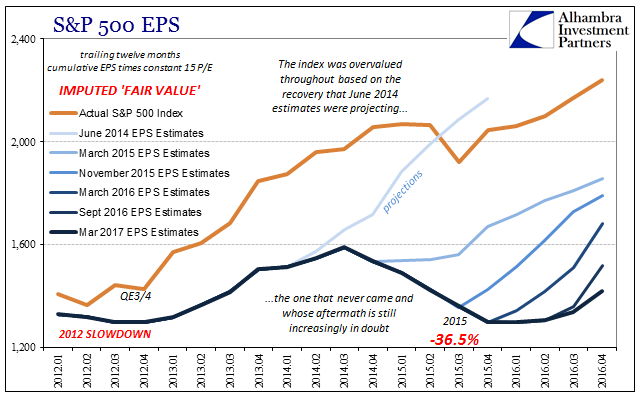

The recovery in earnings is as lackluster as the recovery in economy, a more constructed relationship where stocks are concerned. That leaves share prices, in general, operating on the far end of the probability spectrum; where everything has to go just right in the near future, including whatever may come out of Trump “stimulus” and economic policies. EPS, however, suggests, as the calculations for GDP potential, that that would be a very low probability outcome, including a high risk of “something” going wrong all over again just like it was in 2014.

For shareholders, that leaves them in a precarious position expecting something that just isn’t very likely. Worse, any objective review of economic prospects for years before suggested the very same, meaning that nothing has really changed in terms of the long run except actual reported earnings which are supposed to matter more.

Again, the primary problem was in fundamentally misreading and misinterpreting what QE was – it was not money printing no matter how many times the media repeats the assertion supposedly derived from the editorial standards for what constitutes good authority. What should have been considered to a greater degree was how these views on QE amounted to little more than confirmation bias. All the evidence to that point suggested QE wasn’t working and hadn’t worked, established strictly by the fact that there had already been a second years earlier (and then a third, and then a fourth). From this view, it was far less reasonable to expect EPS for the S&P 500 to ever get near $145.

Therein lies our stock market revisit with the dot-coms, not just in terms of valuations but more so the psychology of them. Stock investors wanted QE to work just as they wanted to believe in the late 1990’s Alan Greenspan was a genius who had engineered a “new normal” then of unparalleled, low volatility prosperity.

In a curious sort of way, overvaluation in this manner actually makes stock prices “stickier.” What I mean by that is that when stocks are so greatly and positively diverge from fundamentals it is very human to think and believe that there must be a reason they are that way, even if that reason isn’t immediately apparent or so often contradicted. From this standpoint of rationalization, why not QE3 or the maestro? Conversely, if stock prices are questionable then it must be because stocks themselves are rationally questioned.

It is the situation where “dumb” money makes all the wrong choices, selling at the bottom or near enough to it after having bought hand over fist at the top. Irrationally, when stocks are so stretched in valuation they can appear as the safest place to be.

In fundamental terms of earnings, there is only further confirmation of a lack of growth, both as a matter of the rebound from early 2016 as well as from the global slowdown in 2012. At $94.54, ttm EPS are almost exactly the same now as when QE3 started, and are only 6.8% more than Q1 2012 all those years ago! For that lack of growth, the stocks in the index are trading in the aggregate at more than 23 times posted earnings. It is the inverse of Keynes, where there is no consideration at all except for the long run and how some unknowable magic combination of policies will surely make it such a happy and prosperous place – even though none so far have come close.

Stay In Touch