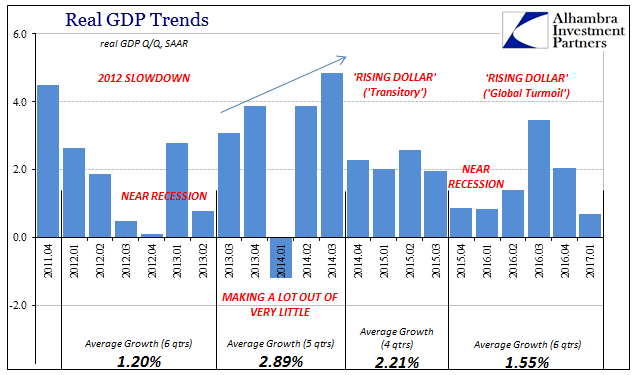

Back on March 10, the New York Fed’s attempt at real-time GDP forecasting predicted that the Q1 2017 estimate would be 3.2%. That would have qualified as another decent quarter, the second out of the past three and somewhat in keeping with “reflation.” As we know today, the advance figure calculated by the Commerce Department amounted to just 0.69% growth in Q1.

The point is not to cherry pick the highest quarterly prediction and make fun of FRBNY. At the same time in mid-March the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow competing model had already collapsed below 1%. Like the New York version, the Atlanta tracker had early on projected better than 3% growth for the quarter. It was at one time in early February just shy of 3.5%, higher than at any point for the other one.

The New York Fed’s parsimonious statement today tersely explained:

Today’s advance estimate of GDP growth for 2017:Q1 from the Commerce Department was 0.7%, substantially weaker than the latest FRBNY Staff Nowcast of 2.7%.

While that was of no value, pointing out merely the obvious, the regular weekly report gives us a clue ironically in trying to explain why we should readily trust its methods.

Extensive back-testing of the model, research, and practical experience have shown that the platform is able to approximate best practices in macroeconomic forecasts. The model produces forecasts that are as accurate as, and strongly correlated with, predictions based on best judgment.

There is a whole lot to that statement covered underneath statistical jargon and buzzwords. That they attempt to “approximate best practices” rather than the results of those practices is especially significant. The New York Fed is trying to model the economy that “should be” rather that the Atlanta Fed’s model of the economy as it actually is. Very important to the former is sentiment, one reason why monetary policy builds itself philosophically around rational expectations and the institutional expectation for successfully manipulating them.

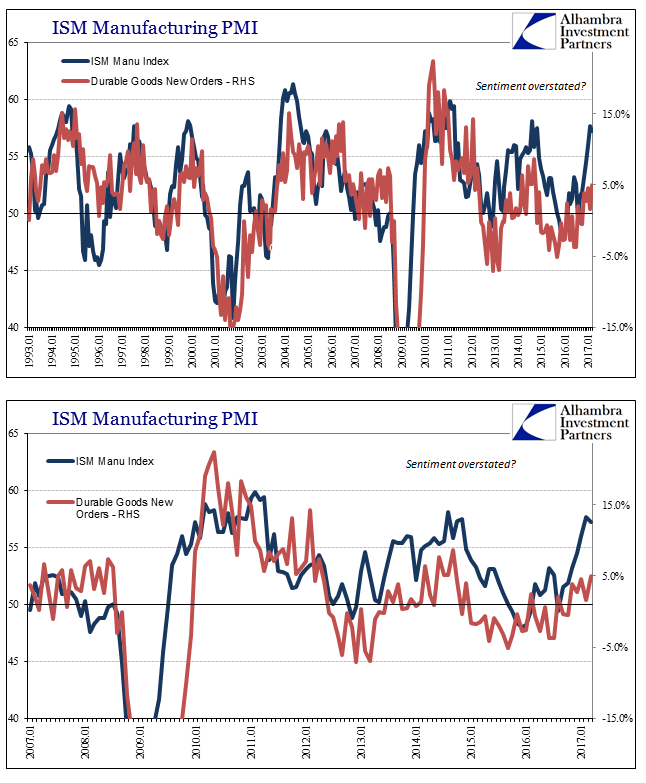

The major disconnect is in the latest quarter entirely one of that area. PMI’s and other measures of business attitudes were through the roof, as were the various indices attempting to gauge consumer confidence. Yet, neither form of sentiment or confidence translated. The difference on the consumer side was especially important given the weight of risks for the future economic trajectory as well as the majority basis for this quarter’s (repeat) disappointment.

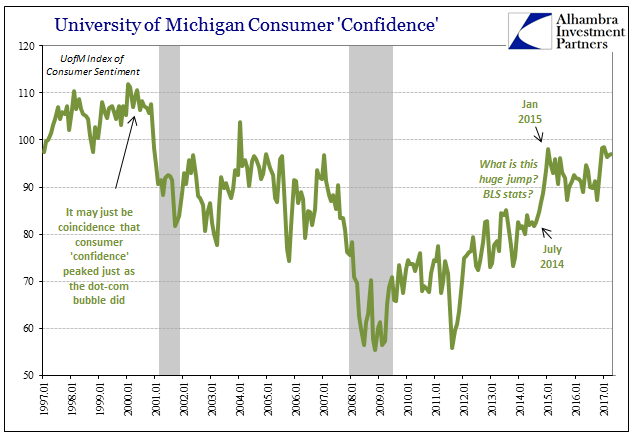

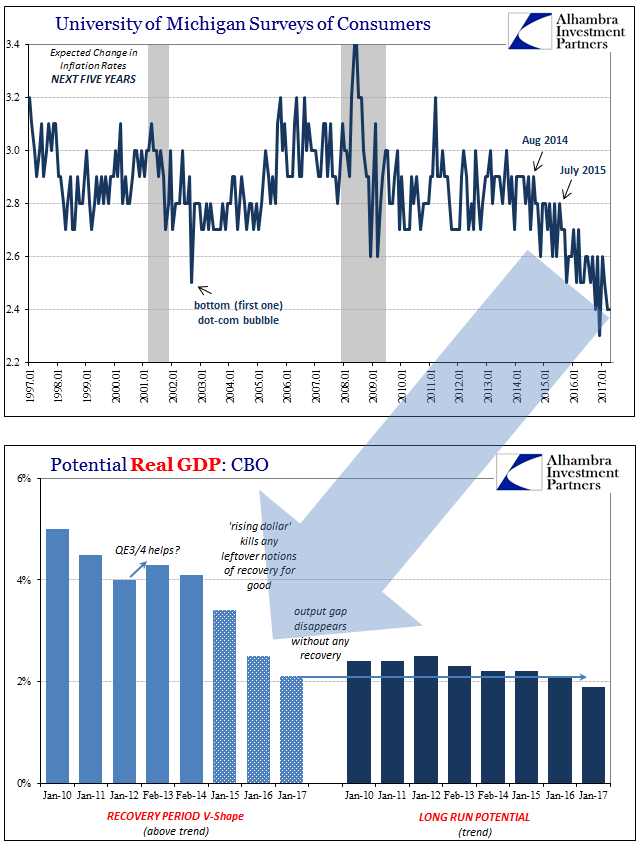

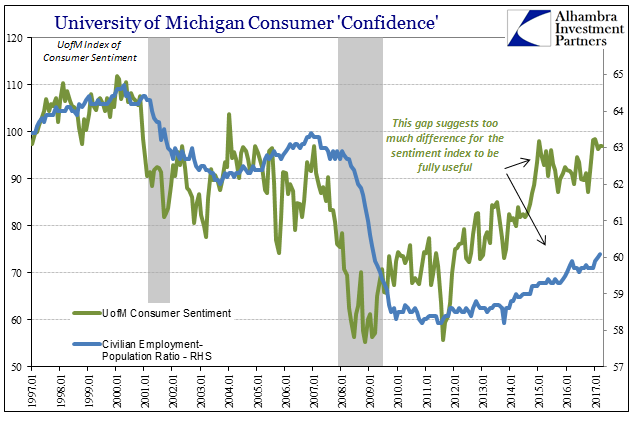

None of this is new, of course, as the discrepancy emerged as far back as 2013. But it found another level importantly in 2014, particularly with respect to consumer confidence. Just when the BLS started reporting the “best jobs market in decades”, the various indices recorded a similar surge in positive consumer emotion. The University of Michigan’s Index of Consumer Confidence was in July 2014 barely above 80, but by January 2015 it was nearly 100 and suggesting normalcy at long last. Taken together, the labor statistics as well as confidence was a powerful mix for mainstream interpretation. Is shouldn’t have been that way.

Consumer confidence relatedly did not fall much as the economy clearly did through the “rising dollar” period. As “reflation” after it has taken hold, it is right back again at multi-year highs; in the UoM format just less than 100 like the days of the housing bubble. That means confidence remained high even though consumer spending seriously decelerated (retail sales were in 2015 and early 2016 among the worst in the entire data series).

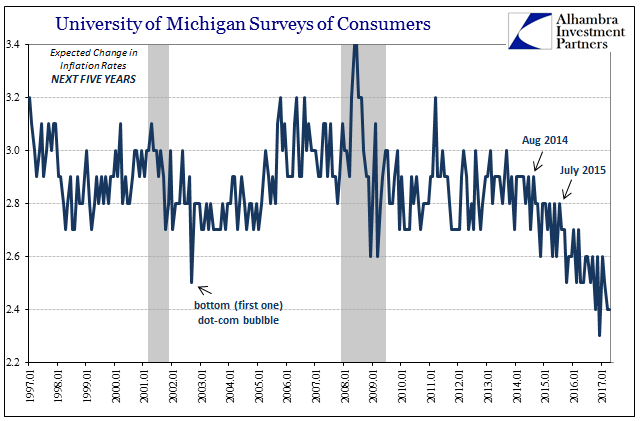

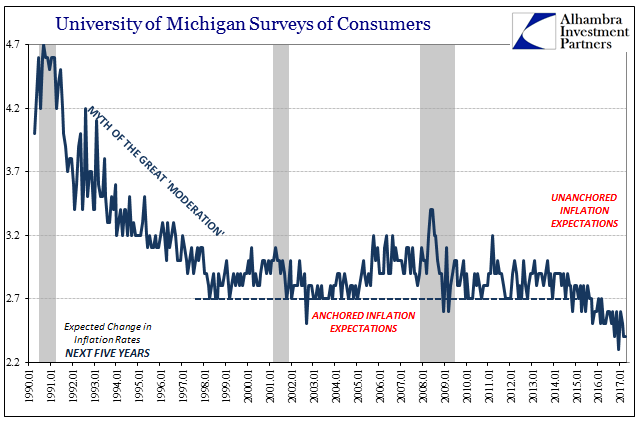

Other parts of the UofM survey did register significant pessimism that more closely matched the trajectory of consumer spending as the economy overall. Inflation expectations, longer-term expectations in particular, clearly showed a hard change and one that occurred at the exact same moment the whole survey was claiming confidence was surging.

How do we make sense of what is clearly a contradiction? I think the answer lies in the space between the New York Fed’s NowCast model and the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow alternate. Consumer confidence indices appear to be reflecting expectations for the economy that “should be” while inflation expectations might better exhibit the pessimism of how things haven’t changed, and are in further danger of remaining that way more permanently. It is reminiscent of the huge divergence between the stock market and the bond market, and surely the latter has to some degree affected consumer thoughts on the “should be” side.

The weight of evidence, such as Q1 GDP, remains all in the wrong direction. What’s left on that other side is merely unbacked mainstream rhetoric and the hollow assurances that amount to little more than agenda noise. Yet, confidence persists. It is dissonance, to be sure, but explainable.

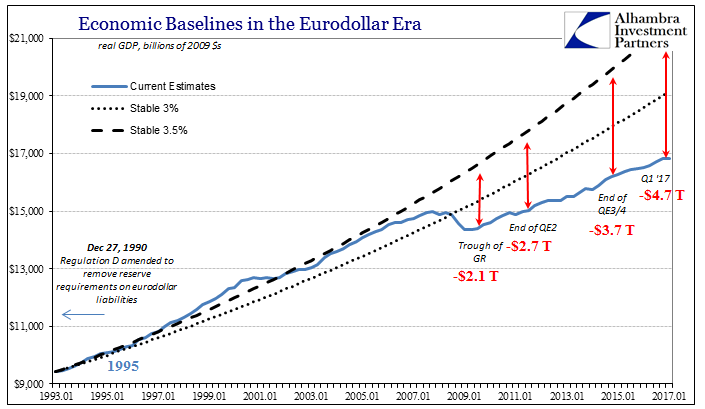

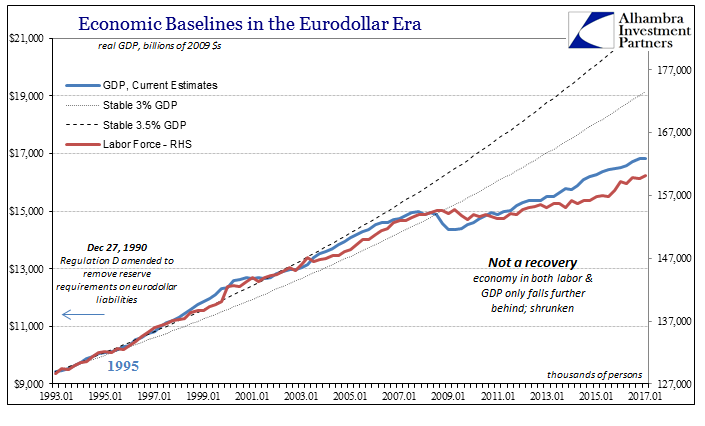

I think what we are seeing expressed is this state of disbelief over the length of depression so far, thus its mere existence. None of us has any experience with a structural dislocation on this scale. Even the Great Inflation, though it lasted for more than fifteen years, was in the opposite direction, meaning that while it was no picnic it was at least characterized by movement and action – especially in labor. This last decade is nothing more than inaction, an economy apparently frozen deeper and deeper into desperate stasis; the figurative embodiment of Dante’s Hell.

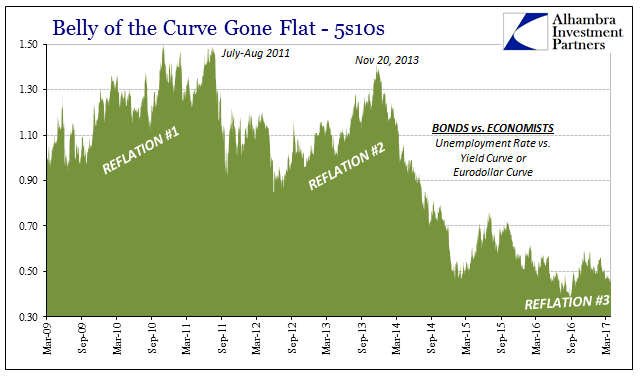

As Japan has shown time and again, the worst case is not recession or even repeated recession. It is stagnation of a kind far more sinister than that of the Great Inflation. At least in the 1970’s there was action and activity. This version is where the economy is simply frozen. In Dante’s Inferno, Hell is not hot, it is increasingly cold as each layer is further removed from God’s true warmth. Heat is passion and life; cold is where living is further stripped away toward the inanimate. The bond market is making that same journey, if not in a straight line, further into the lower reaches as the economy grows colder and colder.

For most of us, this just cannot be; it cannot be possible that there is so little growth and opportunity after ten years of none. Even if predicated on just randomness alone, blind dumb luck, the economy should start to correct at some point. It just doesn’t seem believable that in the 21st century depression of this magnitude and length could happen.

And so the longer it goes on, people seem to believe the greater the chance that something just has to go right. It is a happy a comforting thought, aided in emotional manipulation by the constant mainstream optimism. In that belief, every minor uptick is extrapolated far beyond its true significance as that thing that will surely restore positive balance and order.

Like inflation expectations, however, there are lingering doubts. We want to believe it can’t be this bad forever, but we also have to live to some degree, unlike policymakers and their regressions, in reality. In the middle of 2014, that meant not only could things be bad for such a long time, as they had been for seven years already by that point, they could actually get worse!

This is the legacy of the “maestro”, where “we” can’t make sense of where we are because it just doesn’t seem possible. There is no way that the Federal Reserve, once the standard for all technocratic excellence, could let this happen. Even the QE’s to some degree fall under this cultish existence, for trillions in money printing have to show up somewhere at some point. It can’t be that all the worst cases merge together; that the Fed could totally strike out like that, and the economy stuck without expansion for a decade and more. Who ever heard of an economy that just shrunk?

Unfortunately, we have been studying one for more than a quarter century, which only adds to the seeming impossibility of it all. We have known about Japan for all that time, so it can’t be that we are following that path being so aware of it. That might be, though, where a significant proportion of doubt has come from especially in inflation expectations unanchoring (as well as bond rates and eurodollar futures) because the Federal Reserve for all its posturing and assurances did exactly what the Bank of Japan did – and the results were exactly the same. We want to believe we aren’t Japan, and yet, we know on some level that we are.

I have no idea if denial is a stage of depression, but we have here all the evidence for it in economic terms.

Stay In Touch