Wholesale sales were up 8.3% in March 2017 unadjusted year-over-year. Like other accounts, however, the seasonally adjusted series was not impressed. On an adjusted basis, sales were flat month-over-month, just $50 million more in March than February. It isn’t clear what the problem might be, as the only calendar aberration is Easter that fell in March 2016 but not March 2017.

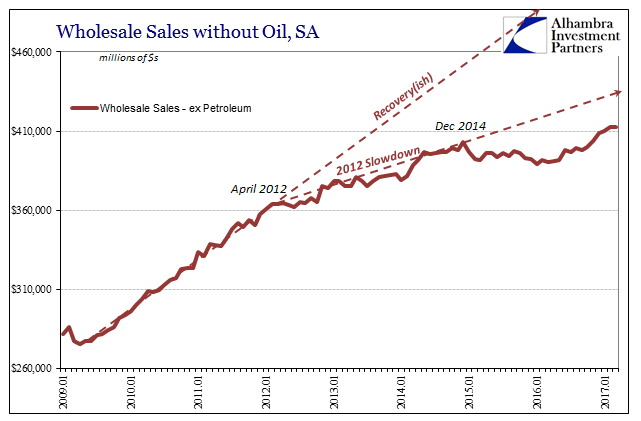

Whatever the case, there are indications of price effects dropping off. Much like inflation rates or Chinese imports (raw material going into China, not finished goods moving from China to the United States), the commodity rebound from the lows of 2016 have been contributing to annual comparisons. The question for analysis is by how much, meaning what is moving these accounts in 2017 beyond price momentum.

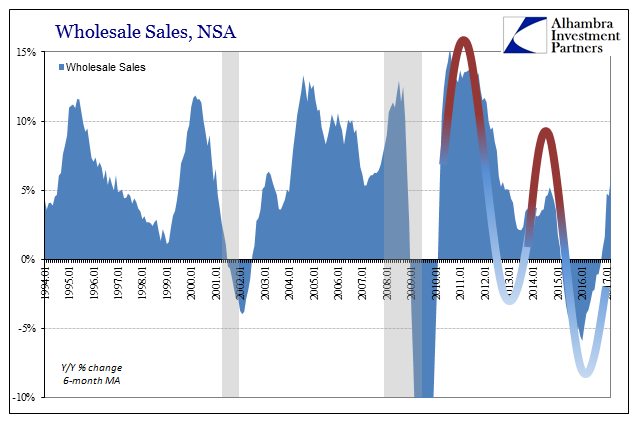

That is the key problem because by almost every account there isn’t much outside of these base effect considerations. Momentum remains conspicuously absent, a result that maybe shouldn’t be surprising in the wholesale level of the supply chain given the low amplitude, elongated trajectory of the contraction that preceded this “rebound.” It is in (almost) every way reminiscent of 2014 (apart from oil/commodity prices).

The 6-month average for wholesale sales growth (unadjusted) is now 5.9%, the highest since the summer of 2012 just before QE3 when Mario Draghi was last making his (apparently still relevant) euro promise. But it isn’t all that much more than the peak of the wholesale sales average in September 2014 (5.2%) just before it all fell apart under the “rising dollar.” Considering the price boost from commodities, the similarities are too familiar.

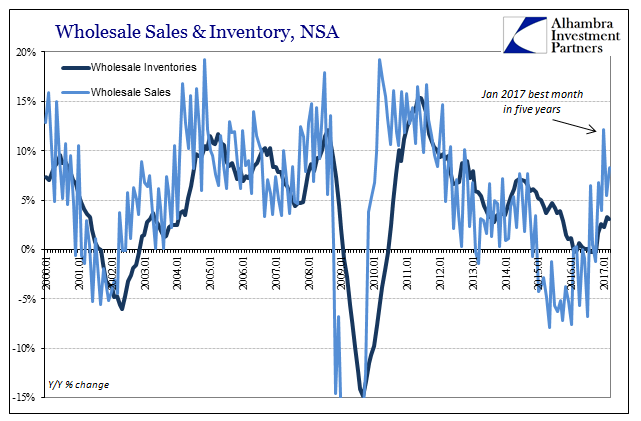

That may be why wholesale inventories have consistently underperformed despite the clear shift in at least sentiment. Wholesale inventories (unadjusted) rose just 3% in March, much less than the 6-7% growth during the 2014 “rebound.” Despite positive sentiment, inventory levels remain elevated simply because they never really declined throughout all that happened over the past few years. At most, inventory growth stalled for much of last year while sales marginally improved, but apparently not enough (so far) to ignite another restocking cycle.

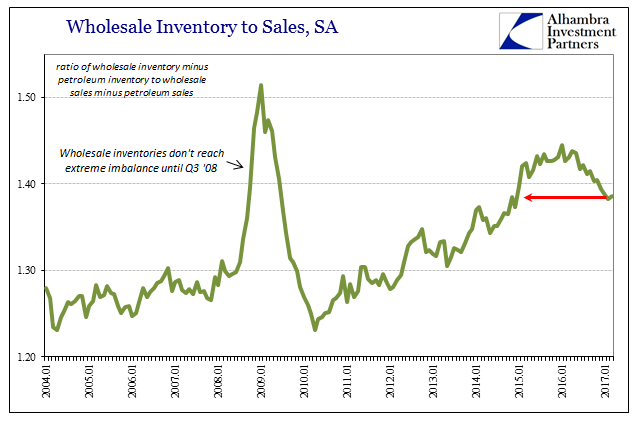

The inventory-to-sales ratio remains far too close to 1.40, a level usually associated with recession. The decline in the ratio last year as inventories stayed even only brought the number down to early 2015 levels, hardly the platform from which to launch widespread, broad-based manufacturing growth that is sorely needed.

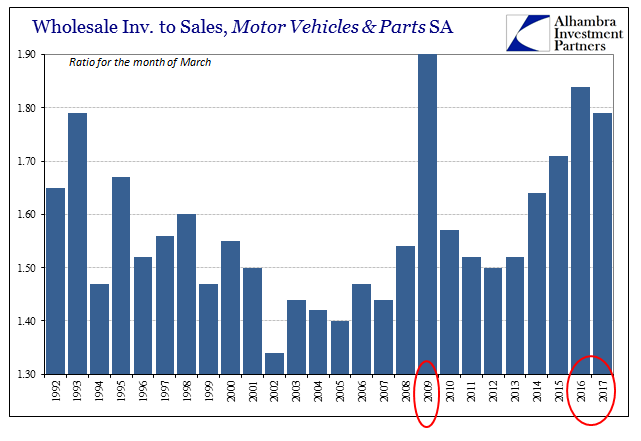

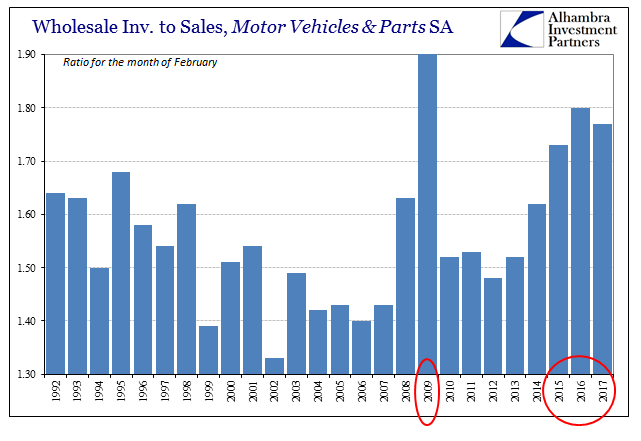

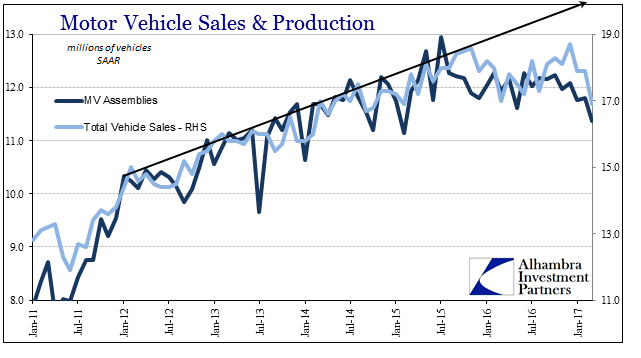

Nowhere is that more evident than in the automobile sector. Inventory levels remain stubbornly high, not much changed at all from 2008-09 type conditions that have prevailed for much of the past two plus years. The ratio for March 2017 was just less than 1.80, an altitude first reached back in October 2015. Other than an anomalous decline to 1.67 in January 2017, the metric hasn’t strayed much at all, meaning that for what minor adjustments have been made to auto production they have not been close to enough to align with slacking sales volume.

On the wholesale level, that is attributable primarily to fleet sales which have been under enormous pressure, but not entirely due to that factor. Flagging retail auto sales are a contributing element to persistently lopsided inventories, despite huge incentives being offered up and down dealer networks.

It is one big reason why there is no economic momentum coming from the manufacturing sector when this is the area where it should be originating. Though these circumstances are unique, as had been the case since 2007, unlike in a business cycle everything is out of alignment acting in almost chaotic fashion. In a recession, or even a near-recession, as have occurred occasionally, economic correlations all move toward 1.0 as everything gets hit and then everything gets better.

In the current case, which has been this way since the summer of 2011, sectors and industries are all disjointed in what almost amounts to noise; the net result of which is persistent weakness where even if there is improvement from one month or year to the next it is always curtailed by “headwinds.” Right now inventories and inventories of autos are the most pressing “headwind” on the manufacturing side.

As usual, though, it all begins with US consumers who despite all the surveyed confidence and optimistic rhetoric aren’t willing or able to indulge. And beyond the next few months, as of right now commodity prices won’t be able to, either.

Stay In Touch