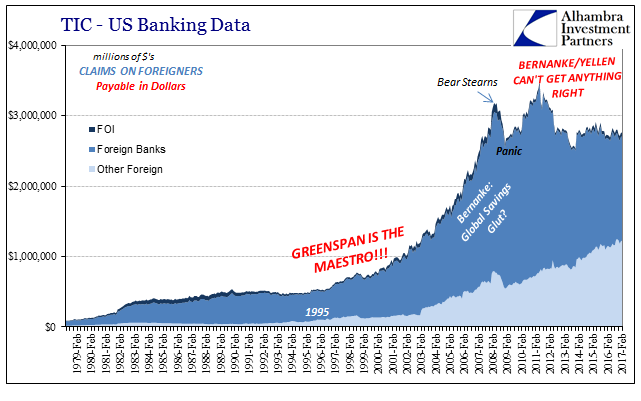

The Federal Reserve defines price stability in terms of consumer prices rather than a stable currency. Up until 2012, any inflation target was implicit in monetary policy behavior rather than explicitly stated as an incorporated aspect. Everyone knew, of course, that the Fed had throughout the 1990’s sought a stable regime of around 2% growth in the PCE Deflator. Furthermore, it was widely believed that it was monetary policy under Greenspan that had achieved it (the Great “Moderation”).

In 2004, Frederic Mishkin argued for an explicit target as a way to transfer Greenspan’s legacy into permanence, realizing his time at the Fed was up in the then near future:

Although inflation targeting in the United States would probably have provided small benefits in recent years because of the superb performance of the Greenspan Fed and the tremendous credibility that Alan Greenspan has achieved, now is not the time to be complacent. It is time to make sure that the legacy of the Greenspan Fed of low and stable inflation is maintained. Adopting an inflation target is the best way for the Fed to do this.

For proponents, a stated inflation target enhances the credibility of the central bank because it makes monetary policy somewhat more inflexible. The Fed will have to do everything in its power to achieve that target, and therefore if you believe the Fed holds considerable power an explicit target actually makes it much more likely to achieve.

Fed Chairman Paul Volcker in 1983 explained it this way:

A workable definition of reasonable “price stability” would seem to me to be a situation in which expectations of generally rising (or falling) prices over a considerable period are not a pervasive influence on economic and financial behavior. Stated more positively, “stability” would imply that decisionmaking should be able to proceed on the basis that “real” and “nominal” values are substantially the same over the planning horizon–and that planning horizons should be suitably long.

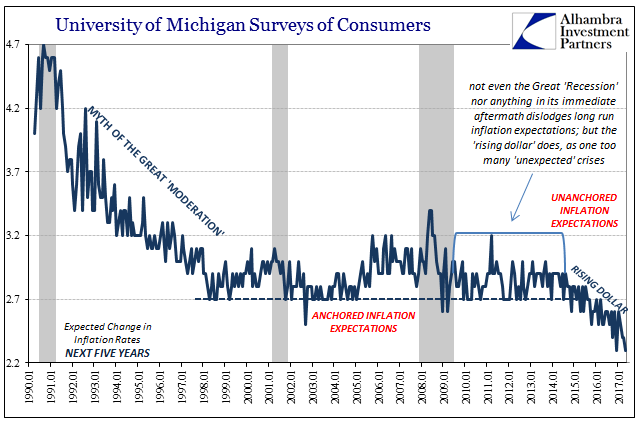

An inflation target means that the Fed is committed and therefore so long as people believe in monetary policy consumer prices and business behavior should act as Volcker describes – taking little note of monetary policy at all, comfortable in bliss believing the best and brightest monetary minds have it all under control. This is why central bankers obsess about the long run “anchor” of inflation expectations, because in those expectations are contained much more than future views on consumer prices.

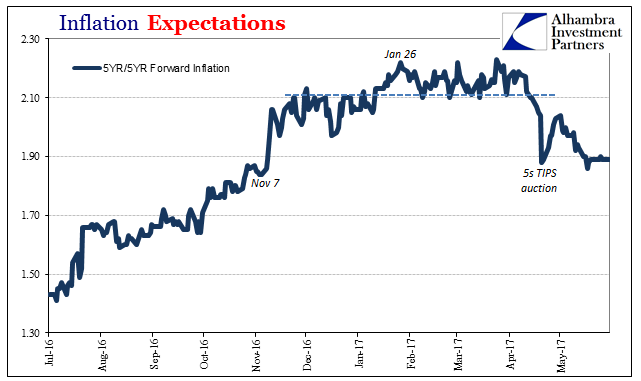

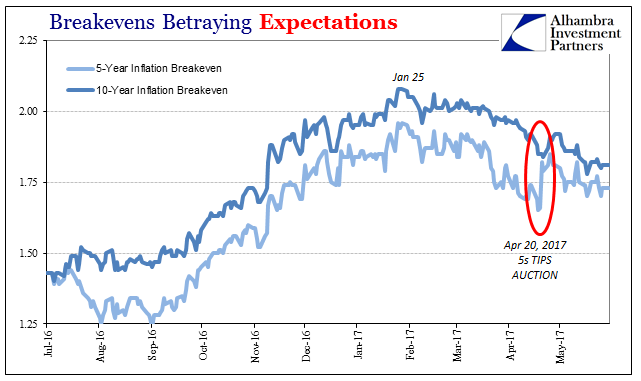

The 5-year/5-year forward inflation rate, a calculation derived from the inflation breakevens of TIPS securities, is one prominent means for demonstrating this monetary stability. By measuring the differences of inflation expectations in a second five-year period above the first, it essentially captures market expectations for whether short- and intermediate-term concerns or trends embedded in breakevens are believed to have an effect on the long run. Prior to late 2008, no matter which direction the PCE Deflator went, the 5-year/5-year forward rate was remarkably stable, indicating that no matter what bond market investors largely believed the Fed had it covered in the short run so as to maintain the same stable long-term economic prospects.

It was simply never much considered a situation where the inflation target could not be met for an extremely long period of time, though the crisis period was a clear dose of real negative potential in that regard.

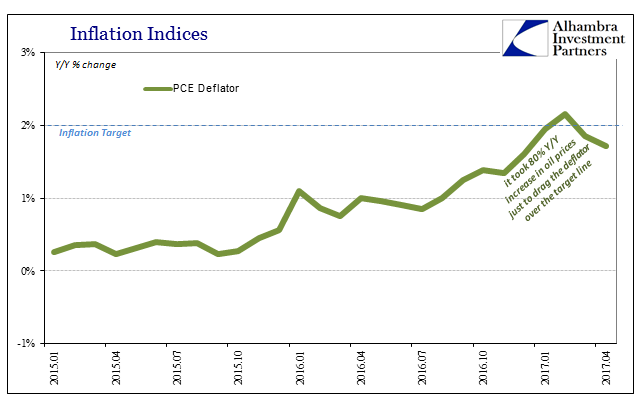

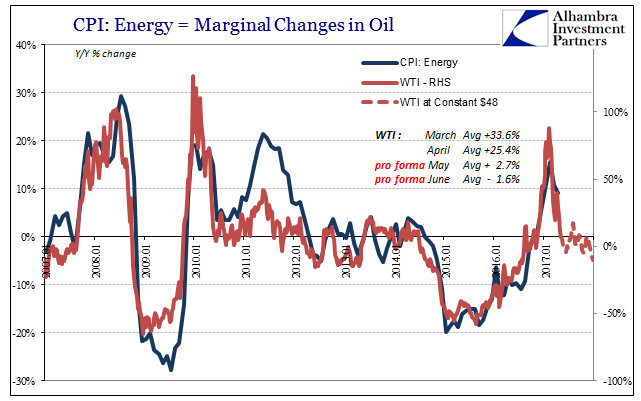

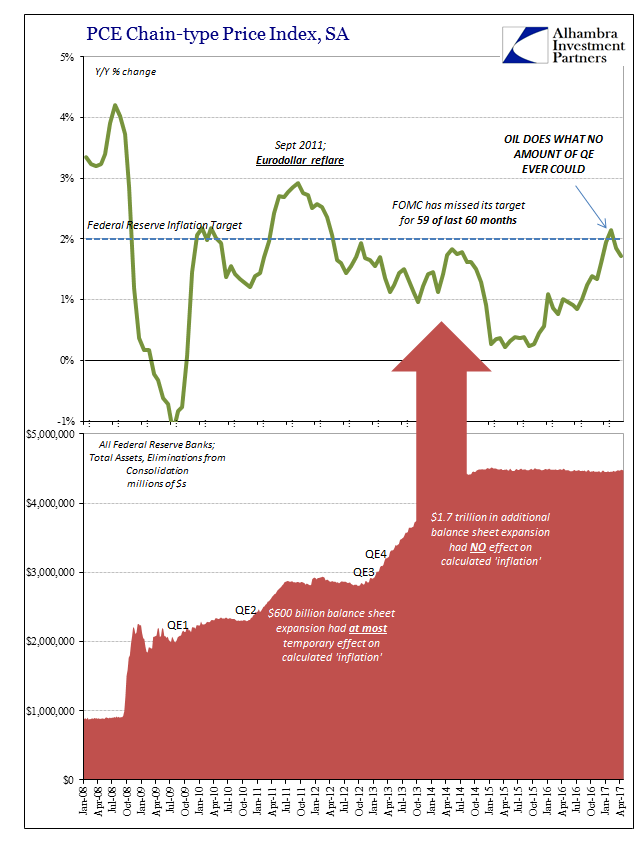

No one who deals in such things will simply ignore a record of such futility. In the 60 months since April 2012, the PCE Deflator has been above the now-explicit 2% target exactly once, just a few months ago for February 2017. That it took an 80% year-over-year change in oil prices to achieve is not lost on the bond market, either.

The Fed speaks in a language where these words have no meaning. Despite it being a full five years now, they still describe inflation using the language of “transitory.” While that may provide some public comfort for policymakers who clearly think people stupid or at least inattentive, the bond market, which is what really counts, long ago stopped listening (rather than being distracted, consumers did too; see below). The 5-year/5-year forward rate broke down starting in August 2014 and has not come close to becoming normal ever since.

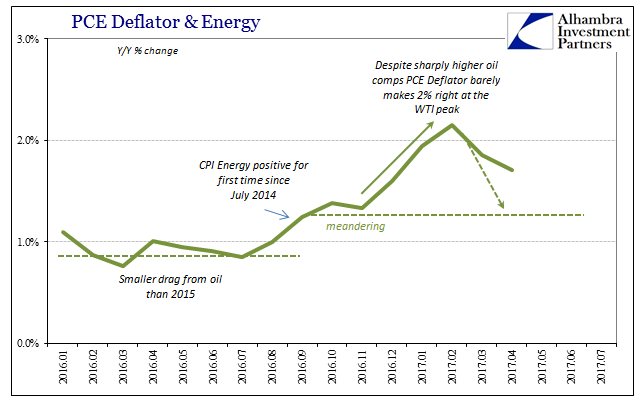

The PCE Deflator for April 2017, the latest data, was just 1.71% above April 2016. April represents the last month by which oil price effects will be of any use to the Federal Reserve. US officials are aware of this process, of course, and were likely content for a few months of reprieve. What is more interesting is why so many in the mainstream were making so much out of so little.

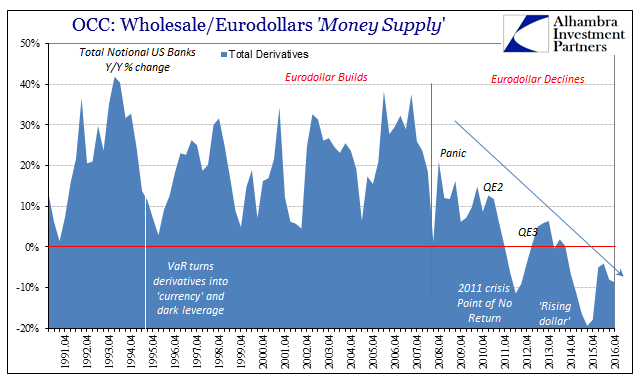

No matter what the Fed had done in terms of interest rate targets or QE, inflation rates bore no correlation to those programs. Even at a balance sheet of $4.5 trillion, there was no resemblance in either the PCE Deflator or the CPI. It was instead the price of oil that clearly and directly decided these measures, leaving the Federal Reserve to reconsider the depths of a real credibility problem that not only discredits recent monetary policy but really the whole paradigm going back to Greenspan.

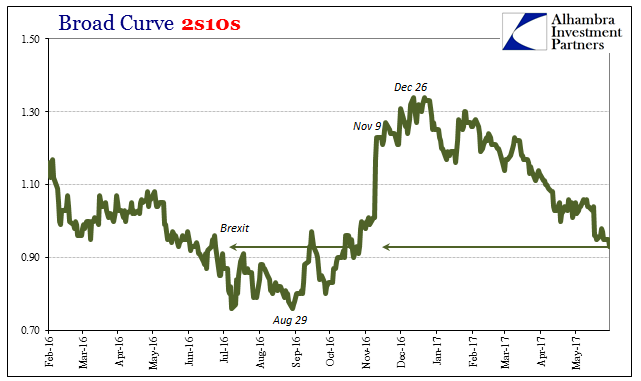

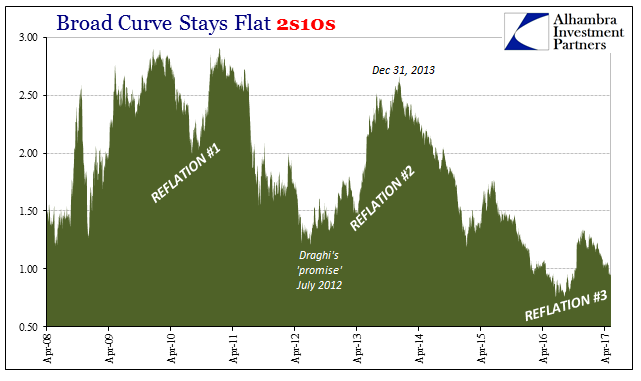

In terms of the 5-year/5-year forward rate, it did appear in very narrow terms at least that the bond market was rewarming to upswing in the PCE Deflator and the CPI, as if the rendezvous with 2% could possibly be meaningful. The forward rate rose sharply especially in the bond selloff in November concurrent with “reflation” and therefore as if inflation would be a part of making it a durable if not permanent economic transition – out of perpetual weakness and back toward something more like normal. It was considered the inflation equivalent of “interest rates have nowhere to go but up.”

In truth, however, the forward rate was like the PCE Deflator, being made of more than what was truly there. It certainly turned higher at the end of last year in tandem with oil price base effects, but it never really came close to suggesting normal. Missing an explicit inflation target for 59 out of 60 months will in any rational system produce such skepticism as perfectly warranted. At best, the forward rate retraced back to where it was in January 2015 just after the first part of the oil crash – in almost perfect reflection of oil prices.

What that means is also perfectly clear once you move past the mainstream’s unshakable preoccupation with the Greenspan legend even today. The market no longer believes that monetary policy has any effect on the long run whatsoever. Forget “reflation”, as the bond market is right now rapidly considering, the Fed no longer rates as much if any consideration. That is why the last “rate hike” produced the opposite effects in almost every place; the bond market “wanted” the Fed to justify its hike by raising significantly at least its inflation outlook. Not wanting to play the fool for the nth time again, the central bank wisely refused in a nod to reality for once.

And so we are back to Volcker’s definition of price stability with a major but necessary revision. Real and nominal values are essentially the same over the horizon but no longer anything to do with the small circle of economists who move an irrelevant interest rate a quarter of a point at a time, and occasionally increase their balance sheet by hundreds of billions without any detectable effect whatsoever. Whereas he had hoped policy would be so successful that people wouldn’t even think about, it has over the last decade been revealed as so unsuccessful that people and markets treat it as immaterial. Monetary policy is just that ridiculous, and markets (and consumers) have finally realized it on a more intuitive level.

The “rising dollar” didn’t so much kill the legend of Greenspan as empirically prove once and for all that it was always a lie. That is why both consumer surveys of inflation expectations as well as the 5-year/5-year forward rate “unanchored” at that very moment. The Fed Chairman was revealed as less than the monetary emperor running around naked, for everyone finally saw that he/she wasn’t even the emperor to begin with; just some unclothed, disheveled guy, now girl, claiming to be the supreme economic ruler ensconced in moneyed splendor.

The fact that oil prices delivered what the Fed never could and now take away 2% inflation is just more evidence that for a very long time there wasn’t any money in monetary policy at all. So long as the eurodollar system was at their backs, it didn’t seem to matter and policymakers were thrilled at receiving so much credit and unearned tribute (Mishkin’s commentary has aged very poorly, to put it mildly). Without it, it’s as if monetary policy isn’t even there because for all that really matters it isn’t.

Stay In Touch