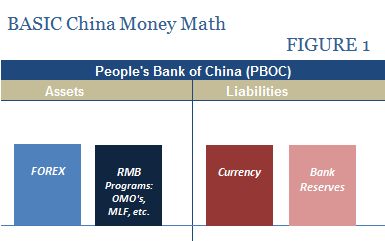

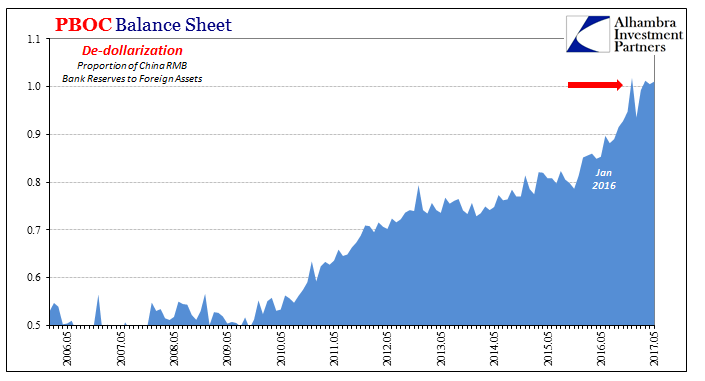

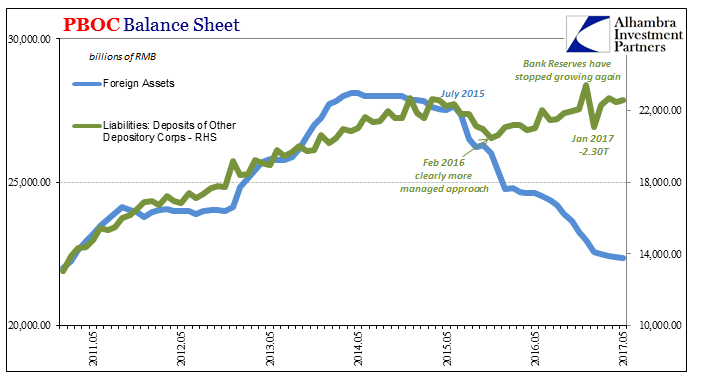

There are four basic categories to the PBOC’s balance sheet, two each on the asset and liability sides of the ledger. The latter is the money side, composed mainly of actual, physical currency and the ledger balances of bank reserves. Opposing them is forex assets in possession of the central bank and everything else denominated in RMB.

Because liabilities need to equal assets, in order for there to be money growth there has to be asset growth. This is, of course, the premise behind QE where other central banks buy largely bonds in order to increase their assets so that the level primarily of bank reserves rise as a direct byproduct. In China’s case, the PBOC spent decades “buying” foreign currency balances first to keep CNY pegged to the dollar and then thereafter its limited daily float.

That meant, as an accounting definition, China’s monetary system was “backed” by these forex reserves first and foremost. There was and remains no legal requirement for the PBOC to act in this manner. The reason for this framework was, to be blunt, legitimacy. China’s monetary system was dollarized because without it RMB wouldn’t have been so stable for global participants, meaning China’s economic “miracle” would have been diminished if not impossible in the first place.

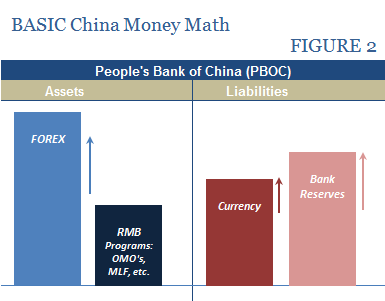

Because of all this, the PBOC needed to do very little apart from manage the price and level of “dollars” inbound. As they accumulated on the central bank’s balance sheet on the asset side, as a matter of basic mathematics the liability or money side could expand even rapidly to meet the needs of rapid economic growth (pre-2008).

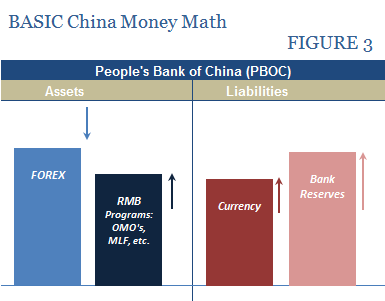

The problem is the reverse situation, that which China has actually experienced since early 2014. If the level of forex assets actually declines, a possibility judged not that long ago to be impossible or at least extremely unlikely for more than a few months at a time, then the offset on the asset side seems an easy decision. As “dollar” balances decline, they in theory can be replaced by RMB liquidity measures of all sorts; from OMO’s and SLF window placements to the MLF and other “targeted” means.

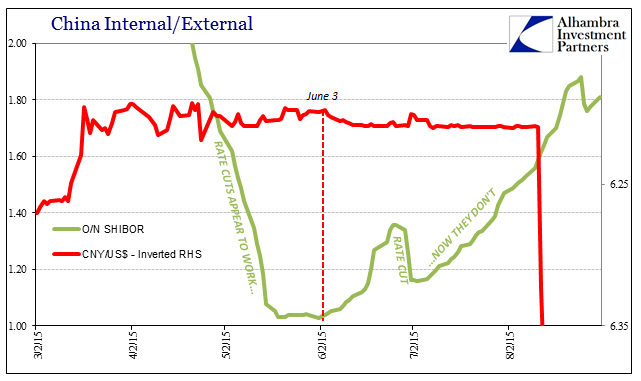

Creating RMB to replace “dollars” allows both currency and bank reserves to rise as might be necessary (even in a slowing economy). The PBOC in 2015 clearly refused to do that, however, instead waiting until February 2016 to activate the vast majority of RMB infusions that have taken place to date.

The complication arises mostly because the issue is CNY meaning “dollar.” The weaker CNY becomes, the more “dollar” “outflows” could take place leaving more for the PBOC to do in RMB offsetting. If the goal is stabilizing CNY, then rapidly increasing RMB as forex assets fall is self-defeating in a very real way.

Again, the PBOC is under no international obligation to restrain its RMB response. The only issue would by CNY stability, a condition into which we really don’t have much insight in terms of official views. It seems reasonable given trading over the past six months that China’s central bank has viewed 7.0 to the dollar as a line in the sand that they don’t want the currency to cross – and have taken increasingly desperate measures to assure that outcome.

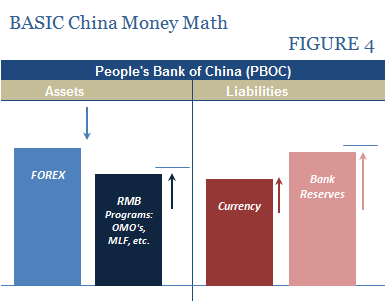

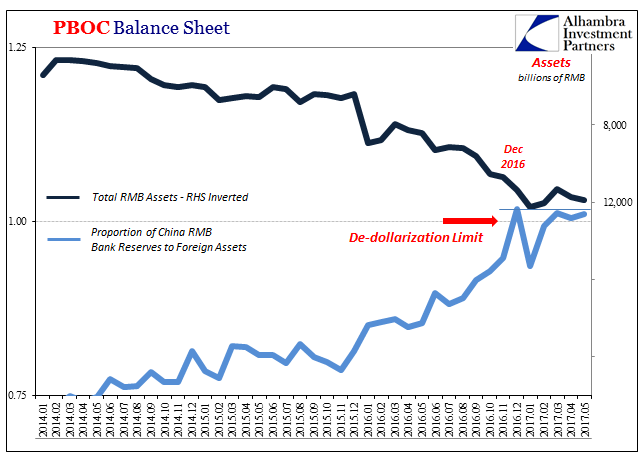

One of those is abruptly halting this de-dollarization process (RMB easing) as a matter of basic China money math. As the level of forex on the asset side of the PBOC declines and RMB balances rise to offset them, it leaves the liability or money side “backed” by a smaller and smaller margin. Thus, Chinese officials have to make a choice: prioritize CNY and allow RMB to be restrained especially in bank reserves, or inject a lot more RMB to equalize monetary demand but then push past de-dollarization and risk further CNY instability.

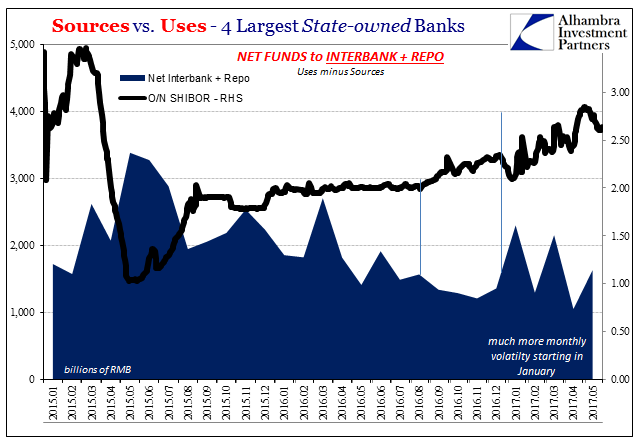

You can argue with the logic, but it is increasingly clear that is the choice the PBOC has made. In December 2016, the level of RMB bank reserves reached parity with forex assets. There was in that month a little more than 1 RMB in bank reserves for every RMB in forex. Since then, through the latest update for May 2017, China’s central bank has gone no further. The consequence of sticking to that constraint is a ceiling on bank reserves which has created all the illiquidity issues running through China’s Big 4 banks.

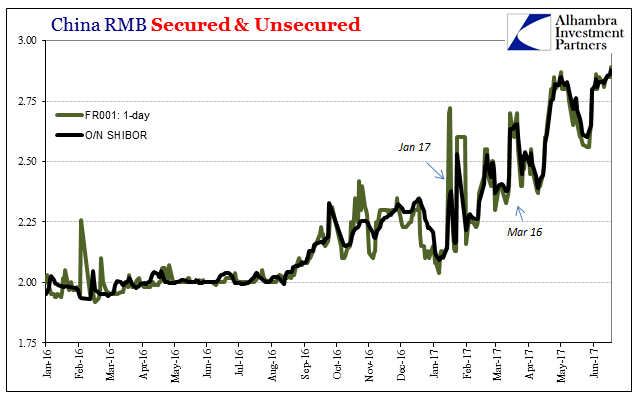

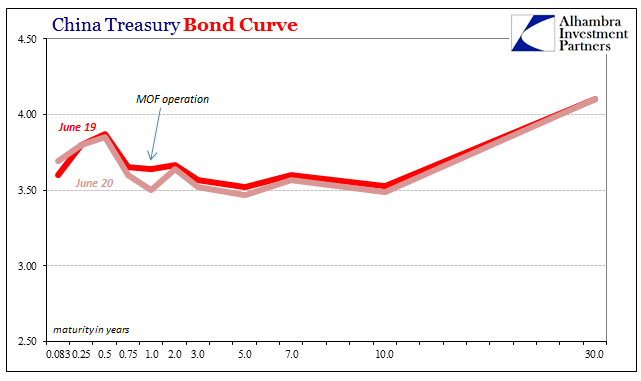

The result is rising nominal money rates as well as more prominently the volatility in which they have done so:

China’s money markets really shifted to what is almost open disorder right in January when the PBOC put in place this RMB limitation. They appear to fear CNY destabilization more than internal liquidity conditions, even as that approaches new and concerning unintended outbreaks.

China’s “tight” conditions therefore are a direct consequence of the “dollar” in (at least) two ways. The first is the direct implications of the PBOC’s asset side, where despite SAFE estimates of “buying UST’s” these balance sheet figures still show a persistent (if shallower) decline. The second is what amounts to fear over de-dollarization, exploring too far the limits of what is essentially moving toward a full fiat regime unconstrained by the monetary characteristics upon which modern China was built.

These often contradictory goals are on a collision course, a possibility the PBOC is surely aware. The intent is very likely as it always is, meaning that the central bank will do its best and hope that the problem will just go away. Most monetary programs of this nature are meant to be temporary because of the tradeoffs and costs involved.

The question is how long the PBOC can hold this stance before something really breaks; one of either the currency, the RMB system, or itself. Though “reflation” has captured the global imagination, including, I have to believe, that of Chinese authorities, it isn’t real and certainly hasn’t proven as much even a year and a quarter after February 2016. “Dollar” pressure and issues remain today, if only to some degree less than in 2015 and 2016.

What has to be frustrating for the PBOC is that they have been through this before, back in the middle of 2015. Their monetary response was entirely different, of course, as they instead allowed bank reserves to contract overall hoping to offset that by unlocking private reserves with several RRR cuts. The timing and overriding conditions were also similar, though at that time it wasn’t “reflation” so much as the “transitory” period between the first part of the “rising dollar” and the more globally violent second.

In other words, China’s central bank keeps attempting various and more extreme measures to alleviate itself from a “dollar” problem that just won’t go away. In that light, the Chinese are at the very least not alone.

Stay In Touch