In late 1999, the Federal Reserve established what was ostensibly an emergency credit facility. On October 1 that year, this offshoot of the Discount Window went live. Its main feature was that it was to be a primary program, meaning that banks didn’t have to prove they could access funds elsewhere first. They could go there freely without fear of regulatory recourse.

The reason for this care was Y2K. The Fed was taking all precautions even though by October 1999 it had become clear any related computer glitches would be minor. For those not old enough to remember, Y2K is synonymous with computer programming. In the early days of computers where processer power was at an enormous premium, dates embedded within important software were coded in two rather than four digits; 79 instead of 1979.

As the new millennium approached, people began to wonder how that might affect these programs that were still in use in vital areas. Stories began to spread, as these things often do, attaining by the end apocalyptic visions of nuclear missiles being launched all on their own (how that might be related to the number of digits in a date was never, of course, actually explained). In the financial arena, the viral story of ATM’s becoming locked up by software confusion seemed to many quite plausible.

The Fed, then, was acting in anticipation of what could be a minor bank run of the 1930’s variety. Spooked depositors might begin to withdraw cash from banks before the change to 2000, leaving those banks vulnerable to perhaps far more than normal liquidity constraints.

Whether or not the US central bank actually believed that the Millennium Bug, as it was also called, was likely or even possible wasn’t the point. The Discount Window extension was more a commentary about people and how economists view them – as emotional children falling prey to ridiculous stories floating about in the breeze. The Fed was preparing for popular stupidity, not the systemic crash of the nation’s monetary infrastructure.

It never happened, of course, as there were very few and minor issues globally, though not for many people predicting otherwise. One of them was former Chicago investment banker Dennis Grabow. He left Morgan Stanley in the throes of the dot-com bubble in order to buy into a West Coast tech company. It was there where he was purportedly exposed to the seriousness of Y2K. The fact that so many firms were working diligently years in advance instead of proving how serious it was being taken to Mr. Grabow fomented visions of The End.

So he started a hedge fund appropriately named Millennium Investment Group, and began soliciting and advising investors on how to prepare for Armageddon. As he told the Chicago Tribune in March 1998:

I got into this issue, and `Oh, my God.’ This is the event that bursts the bubble. This will lead to the greatest transfer of wealth in the 20th Century.

On January 7, 2000, however, his premonition was already dead. He said then, “Those of us who have been following this issue are quite shocked that we’ve had this seamless transition.”

Grabow was wrong, very wrong, but something, however, did change around Y2K. In hindsight, the dot-com bubble was very long in the tooth, but it was more than that. It had nothing to do with the computer programming guts of global systems, but instead may have been related to the spread of global systems especially in the financial, thus monetary, space.

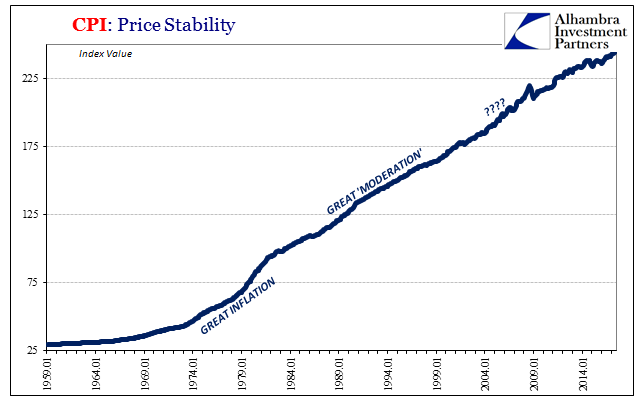

If we examine just a very basic chart of the CPI index, three great periods immediately stand out. The first, the Great Inflation, matches perfectly our perception of the late 1960’s and the decade of the 1970’s. The second, the Great “Moderation” is highly debatable, but in the context of the CPI it was a prolonged period of low and stable consumer price inflation.

The third, however, isn’t marked in any economics textbook. Many if not most of them declare the Great “Moderation” all the way until 2007. But the Great “Recession” and its aftermath did not, as economists would have you believe, just spring up out of nowhere. There were precursor warnings embedded throughout the decade of the 2000’s starting with (not precisely) its first days.

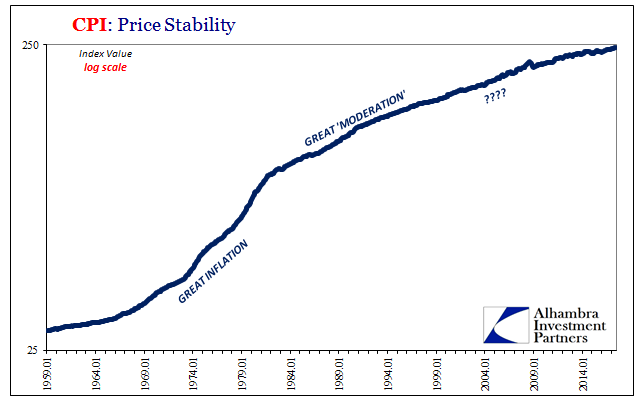

Even on a log-scale chart of the CPI, this third age of inflation conditions is perfectly clear. We focus so much on the year-over-year change to deliver the verdict about monetary conditions that maybe we don’t notice other dimensions. In this case, the CPI though still relatively low year-over-year became far more volatile month-to-month in how it stayed that way. It is still like that now, suggesting perhaps a single “Great” for the whole of the 21st century. An unbroken Great Uncertainty?

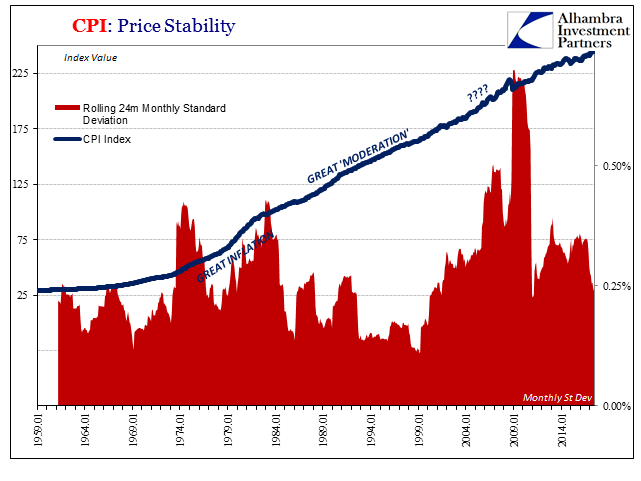

A quick run of standard deviations shows this to be the case, with monthly volatility rising right around the year 2000. The fact that a 2-year standard deviation in 2004 was as much as it was during the Great Inflation suggests something was indeed different; we would expect a high rate of (upward) variability when inflation is running at near and above a double digit annual pace. But at around 3% and less?

Volatility in consumer prices reflect monetary uncertainty, even if not directly related to monetary policy and the effective global dollar (really “dollar”) situation. This should not be all that surprising given what transpired; a “New Economy” promise that looked to be like a permanent plateau of new prosperity in the 1990’s was turning out to be very different in the 2000’s; an asset bubble bust that punctured a lot more than just ridiculous stock valuations related to those promises; and a radical economic transformation that was as downplayed as it was misunderstood.

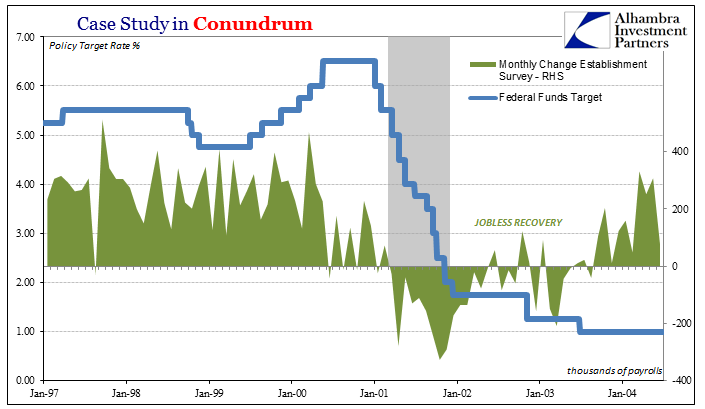

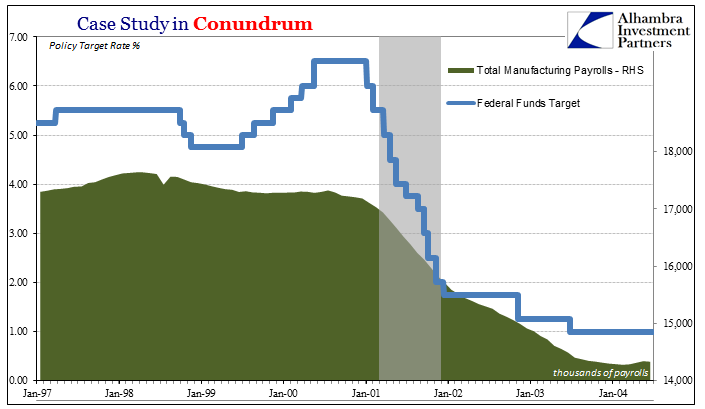

That last one related to the central problem of the 21st century – the departure of so much of the American manufacturing base for foreign shores. There was no apparent reason why the dot-com recession and its predicate conditions in 2000 would lead to such a massive and still unappreciated productive shift. The contraction was the mildest on record, yet the manufacturing sector in the US responded as if Dennis Grabow had been correct.

Monetary conditions had changed, unbeknownst to the Fed or many people around the world. The fully mature eurodollar suddenly made it practical to finally fulfill Ross Perot’s warning. There was ample global money, to an extreme, to finally realize labor savings in the offshoring of primarily manufacturing capacity.

The effect on the US economy, however, from that monetary evolution was drastic and mostly negative; a burst of consumer debt, primarily mortgages, financing largely consumption of goods that at rather wide margins this economy no longer produced. It’s no wonder consumer price behavior became so uneven, as the US economy’s experience in the late eurodollar period was being radically redrawn.

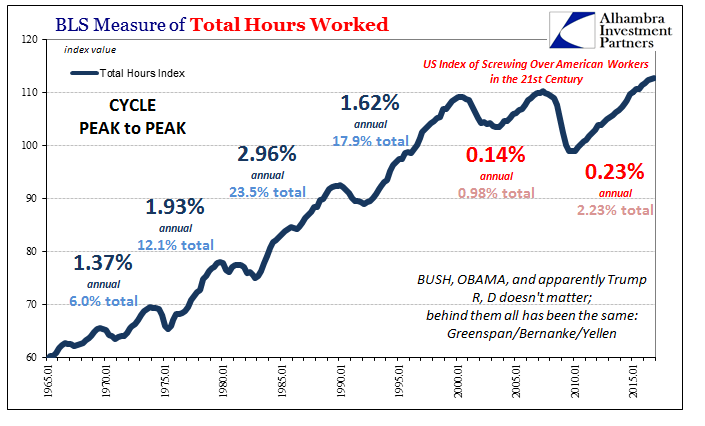

How is it possible that Americans in 2017 work in the aggregate barely more hours than when the meek Y2K switch occurred? Janet Yellen would like you to believe that it is post-2008 opioid users and retiring Baby Boomers. That’s just not the case, however, as the US’s labor problems began much earlier, coincident to what was a monetary inflection. Before 2000, the eurodollar buildup, which appears to be smooth and uninterrupted from what little quantity measures we have, benefited greatly if artificially the US economy. After 2000, it benefited far more the global economy (particularly EM’s) outside the US (“weak” dollar).

And as has to be stated repeatedly, starting with the events that became the Great “Recession”, it now benefits nobody.

The Fed almost two decades ago acted upon silliness in order to from their view protect us from ourselves. Nobody, however, was acting to protect us all from the Fed’s utter monetary dereliction. Keynes said the long run doesn’t matter, but he was so clearly wrong on that count. Y2K wasn’t really a computer problem; it was the demarcation line for the long run, the arrival of the Great Uncertainty.

Stay In Touch