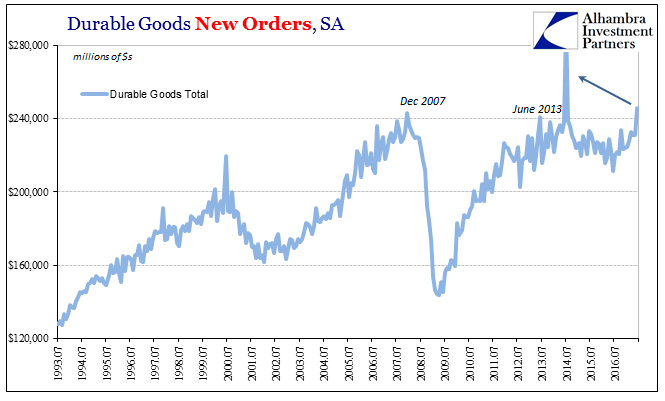

Durable goods orders were up a seasonally-adjusted 6.5% in the month of June 2017. Nearly all of that gain, however, was due to a jump (131%) in new orders for civilian aircraft. That meant demand for transportation equipment, a highly volatile segment, rose 19% in the month. Excluding all that, durable goods were up just 0.2% month-over-month.

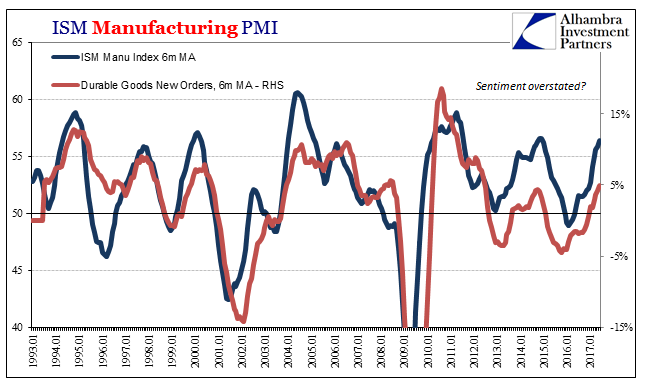

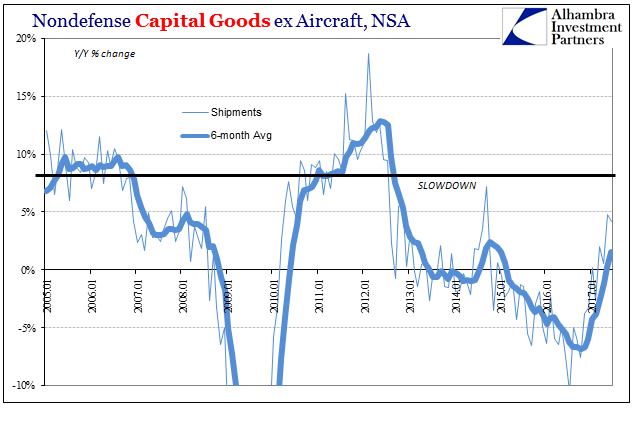

Sentiment indicators like the ISM Manufacturing PMI suggest ebullient conditions that just aren’t matched by activity levels. Halfway through 2017, that shouldn’t any longer be the case. You can understand some lingering problems especially given the nature of the downturn/manufacturing recession, but long before June those should have fully disappeared.

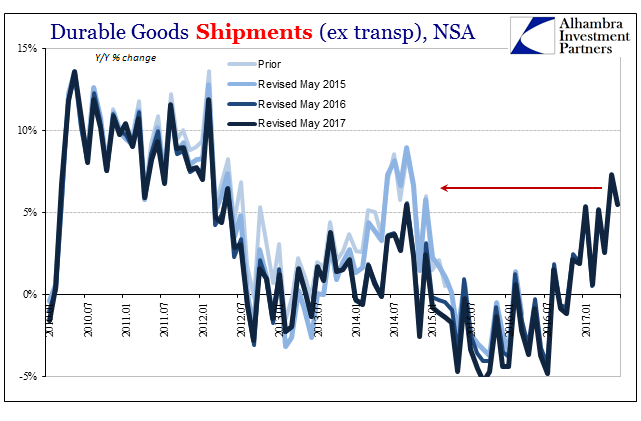

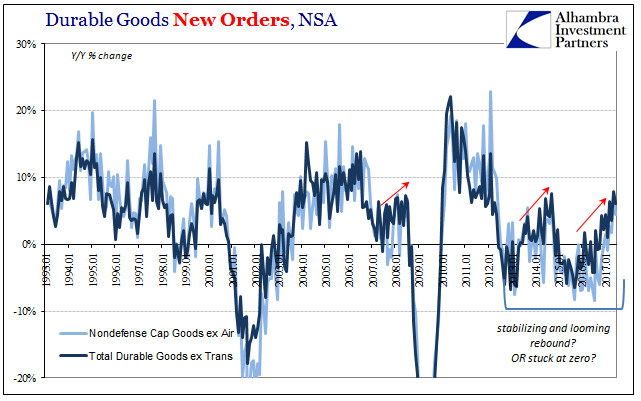

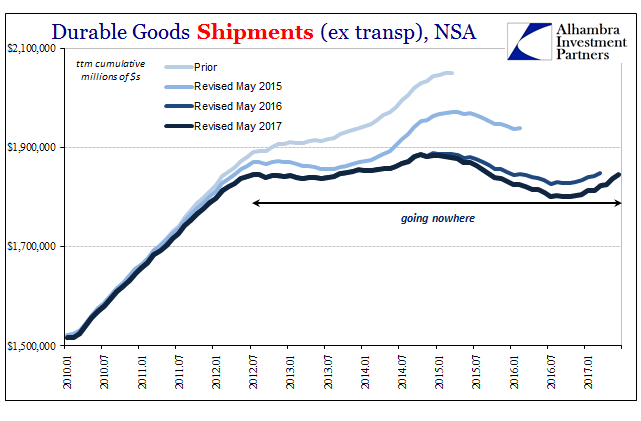

Unadjusted, new orders for durable goods in June 2017 were up only 6% from June 2016. According to both the adjusted as well as unadjusted figures, last June was the bottom or trough in terms of durable goods. Shipments a year later are up only 5.5%.

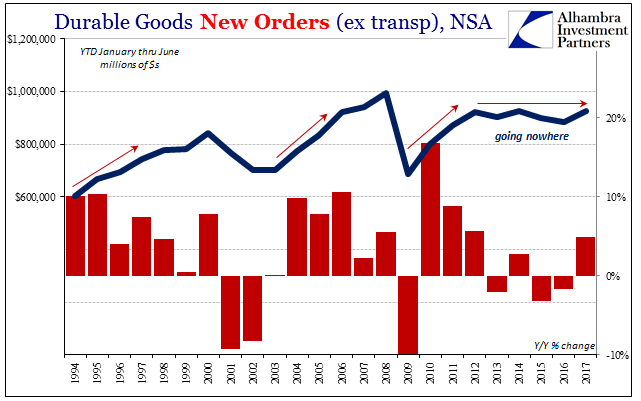

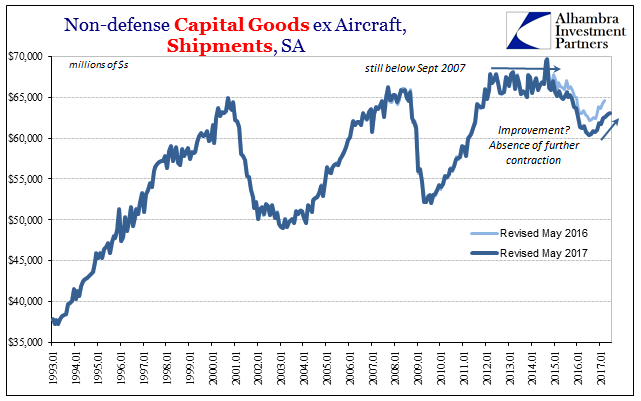

These growth rates are consistent with levels last seen in 2014, even more so when compared to those before the last two benchmark revisions reduced dramatically these manufacturing sector estimates. It was also in the summer of 2014 when a jump in civilian aircraft orders (for Boeing) distorted durable goods figures that ended up being the peak before the downturn.

Year-to-date, durable goods orders are up just less than 5%. That is about half the growth rate historically expected during an upturn or cyclical change. In 2004, for example, durable goods orders were in the first half up 10% from the beginning six months of 2003. Likewise, in 1994 (and again in 1995) during the bond market massacre and the supposed Greenspan-engineered soft landing durable goods demand rose by the same 10%.

Over the last five years, ever since the 2012 slowdown, the manufacturing sector has gone nowhere. Alternating between only shallow contraction and its absence, there is no indicated momentum that would suggest breaking out of an alarming historical aberration. You just aren’t going to find any economic account where year after year the net result is no expansion. Even recessions have always been followed by swift recovery, leaving the contraction as but a temporary interruption an otherwise the clear upward trajectory.

It is the same for capital goods, too. This clear longer-term deficiency is usually downplayed in the mainstream as a small segment of an otherwise service-oriented economy. That may be technically true, but much of that service economy is dedicated to the sale and transportation of goods, so second order effects are substantial. In addition, manufacturing conditions here as well as overseas have been far better indicators of the overall marginal economic direction than other measures like the unemployment rate.

Having experienced that downturn in 2015-16, some in the media are starting to get it:

Spending on durable goods accounts for a small part of American economic output. But changes in durable goods orders often signal where the economy is headed; so forecasters and investors watch the report closely.

They didn’t really before, especially in 2015, often dismissing weak numbers outright (even before the downward benchmark revisions that never get reported), but maybe they do now. The reasons they give:

U.S. industry has rebounded from a slump in late 2015 and early 2016, which was caused by cutbacks in the energy business and a strong dollar that makes U.S. goods costlier in foreign markets.

Oh well; one step at a time, I suppose. It could be interpreted as a sign progress that at least these growth rates estimated for June were for once not widely characterized as “strong” or “robust.” This particular article even went so far as to explicitly qualify the reported estimates, explaining, “the June numbers aren’t as impressive as they first appear.” That could be, however, nothing more than the difference between who is now, and was then, occupying the White House.

By contrast, three years ago Tuesday the same Associated Press reported on what were really similar durable goods numbers in very different terms:

The strength last month came from solid gains in demand for commercial aircraft and machinery. Analysts expect economic activity will strengthen in the second half of the year, helped by stronger factory production.

The 0.7 percent overall increase was in line with economists’ expectations and pushed total orders to $239.9 billion. So far this year, orders are up 3.5 percent over the same period last year.

Analysts were encouraged by the solid rebound in June, saying it should set the stage for further growth in coming months.

It didn’t set the stage for anything in 2014 because nothing about 2014, especially in manufacturing, was actually strong and encouraging. Instead, as I wrote on the same day three years ago:

There has been little change in the pace of growth, as these segments are clearly stuck in the rut that seemingly captured everything in the middle of 2012. While there is growth, it is nothing like what we should see in a true recovery or sustainable growth environment. In June, once more, same story.

I can sympathize to some small degree with the media. Classifying what wasn’t strong as strong all that time for whatever reasons up to and including politics was just as tedious and dull as it is for me to now basically rewrite the same things from 2014. For five years now, the manufacturing sector, which truly matters, has suggested what should be totally impossible, but in a way that, as I wrote then, “The durable goods report has become one of the most boring and uninteresting of all the major data series.”

It still is, though by all convention it shouldn’t be. In only that way is it interesting.

Stay In Touch