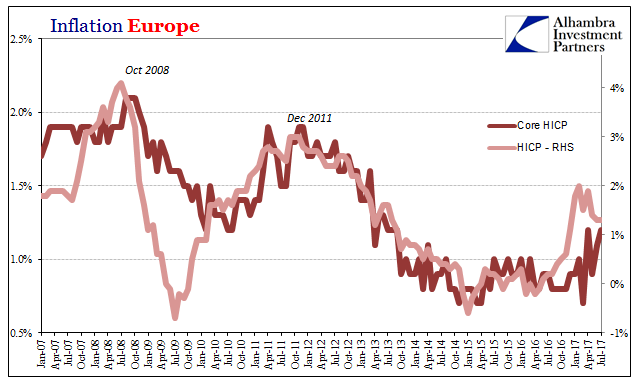

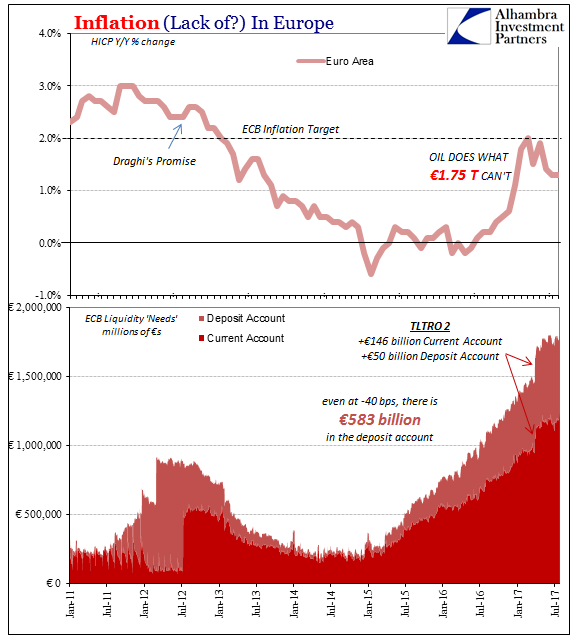

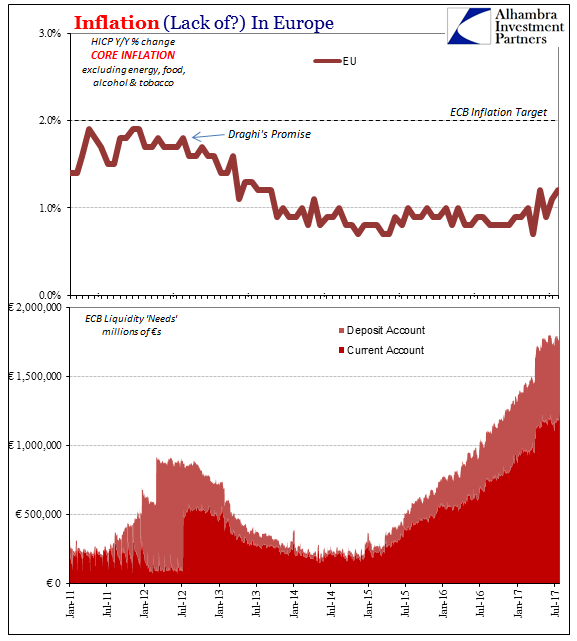

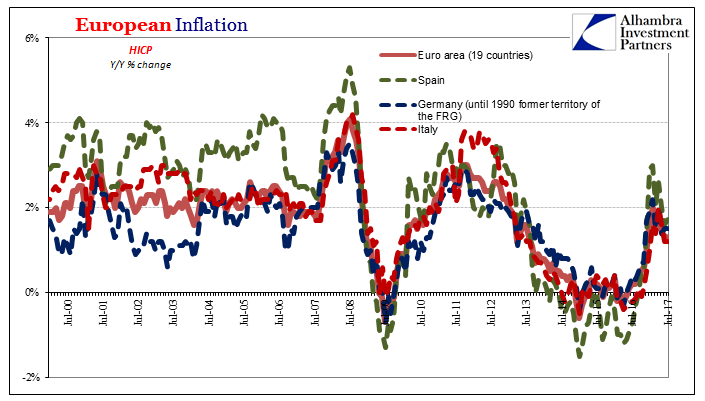

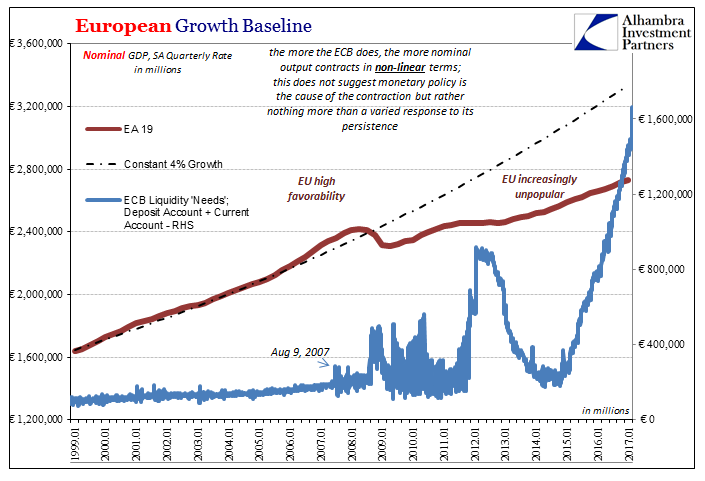

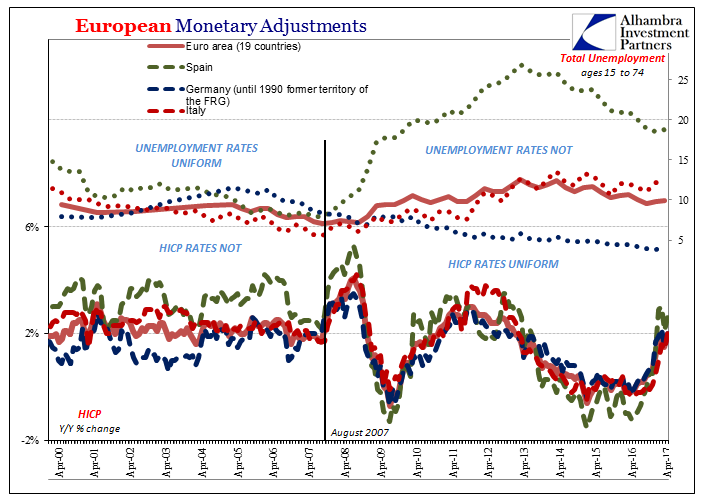

Inflation in Europe was in July 2017 once again underwhelming. Eurostat’s HICP inflation index grew at a 1.3% annual rate for the second straight month. Other than for February 2017, the inflation rate has been less than the ECB’s 2% target for four and a half years. During that time, Europe’s central bank has vastly expanded its liquidity facilities (twice) and its balance sheet (PSPP, or QE).

Core inflation, or HICP less energy, food, tobacco, and alcohol prices, rose at a 1.2% rate for the second time this year. That level of price change is the highest since 2013, which has for many economists confirmed the first part (“hawkish”) of Mario Draghi’s apparent flip flop. But the core rate hasn’t been 2% since November 2008, and hasn’t been close to the target since, unsurprisingly, December 2011.

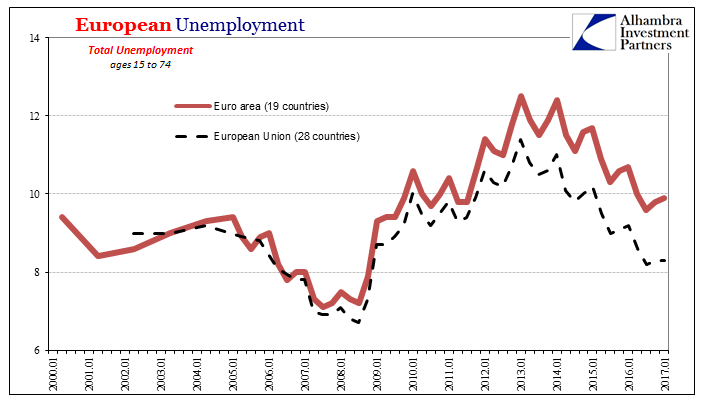

A good part of the reason economists are encouraged by at least the direction of these inflation estimates is unemployment. As in the United States, the unemployment rate is falling, which gives them a sense of a moving recovery. The further expected reduction in labor market slack should therefore increase competition for workers, raise wages, and then finally push up inflation rates in the near future to successful policy completion. The ECB will then be vindicated and everything goes back to normal, even if a decade afterward.

Examining unemployment data, however, one actually comes away with the opposite sense. The rate is falling, to be sure, but the manner in which it is indicates instead why Europe’s economy remains far from healing, and ends up adding to the negative impression left by inflation estimates.

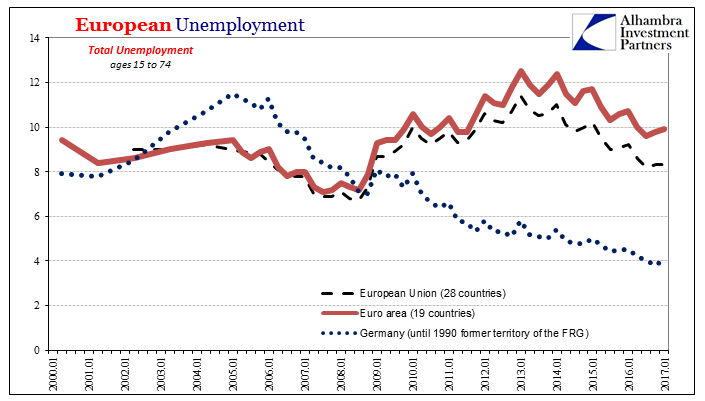

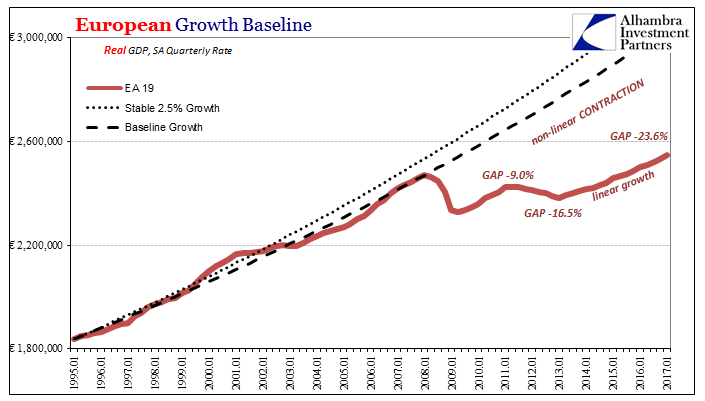

As of Q1 2017 (Eurostat’s Q2 estimates are not yet available), the official unemployment rate for the EA19 countries was 9.9%. That’s down from a high of 12.5% reached during Q1 2013 in the thick of re-recession. This reduction in level corresponds with positive GDP results, clearly suggesting that at the very least Europe’s economy is not still contracting.

But that improvement even after four years (sixteen quarters of GDP positives) has only brought the unemployment rate down to where it was in 2010 and 2011 before re-recession. The rate remains considerably higher than the 7.2% unemployment in Q3 2008 when the worst of the global Great “Recession” truly began.

The reason for that is the scattering of national unemployment rates, often drastic. In other words, each of those 19 countries has experienced very different economic conditions since the great global monetary event. For Germany, it’s as if there wasn’t either much of a contraction in 2008-09, from the perspective of the unemployment rate, or any re-recession in 2012-13 at all.

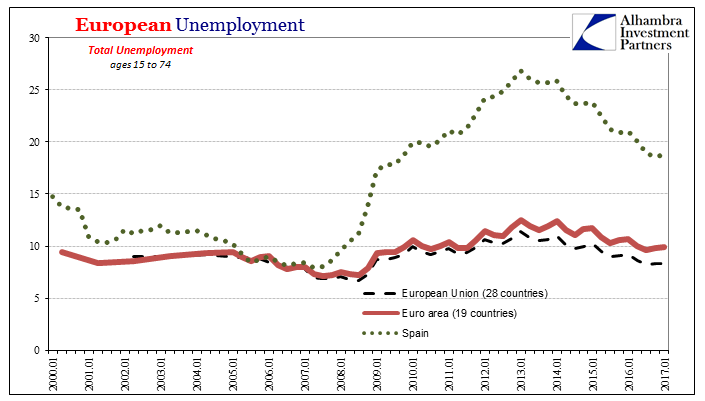

But while German unemployment has been declining particularly since 2010, in Spain it has done the opposite. The unemployment rate there was 7% in Q3 2007, then exploded higher to almost 18% by the official end of the Great “Recession.” The initial aftermath was for Spain almost worse than the event itself. By Q1 2013, Spanish unemployment was an unthinkable 26.9%. Like the rest of Europe, it has since come down as the economy stopped (linear) shrinking, but even in Q1 2017 Spain’s unemployment rate was just about 19%.

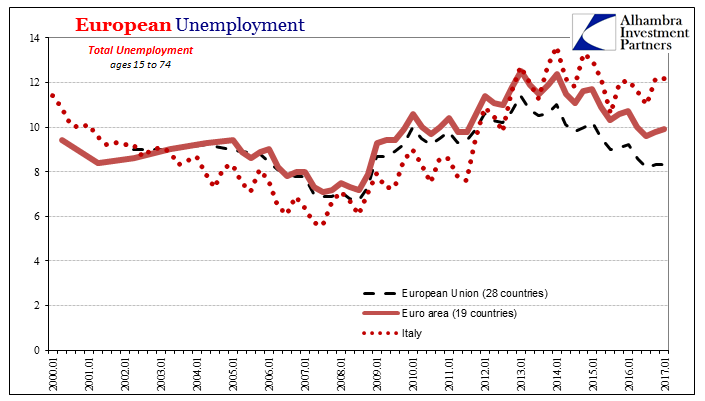

In between Spain and Germany is Italy. The Italian unemployment rate has behaved more like the overall total for the EA19 group, if with a slightly higher beta. From a low of 5.6% in Q3 2007, Italian unemployment peaked at 14.1% in Q1 2014, fell to less than 11% in the third quarter of 2015, and is now higher again at 12.2% in Q1 2017.

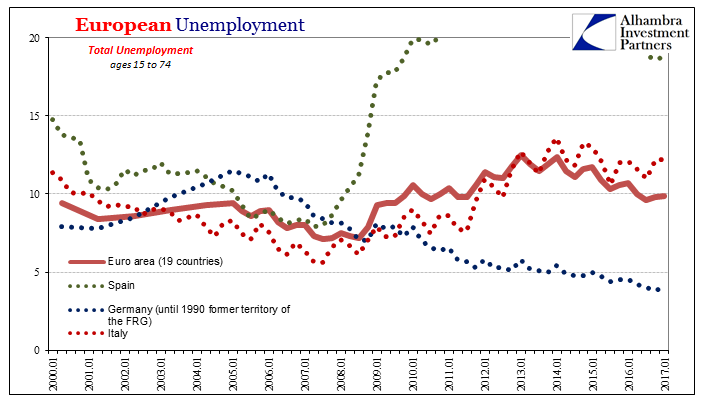

What makes these differences truly notable is that this dispersion of unemployment rates is entirely a post-crisis phenomenon. Prior to the Great “Recession”, unemployment in Europe was far more harmonized (as it should be).

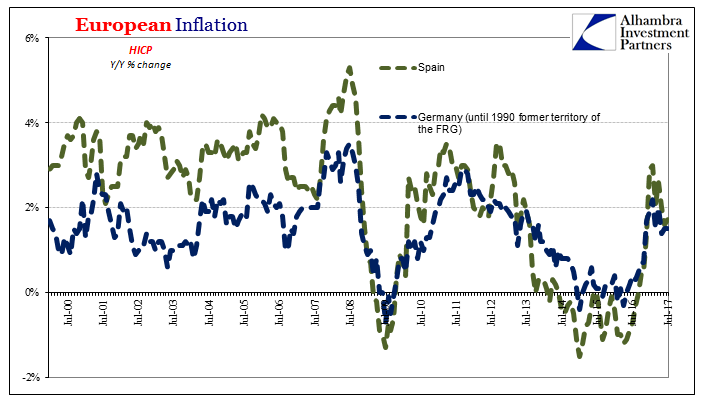

This is the opposite for how national inflation rates have behaved. Before the middle of 2008, really the outbreak of global monetary panic that July, HICP rates in each of these countries was non-uniform. Then, as if attracted by some great unifying element, inflation rates post-crisis have acted in almost lockstep.

Consumer prices even in the two polar opposites, Germany and Spain, have after 2008 become almost completely alike.

What all this shows is an economic (small “e”) phenomenon as old as economics. Various European countries are forced to undertake the burden of monetary restriction through unemployment. But it is not a uniform pain, however, as countries like Germany and the Netherlands have fared far better than those in the PIIGS. Why?

It is as I wrote last week chastising Mario Draghi for not keeping his so-called promise:

What we find instead is that the biggest threat to the euro was not the North/South divide, but that the entire European economy was malfunctioning. In that way the focus on the PIIGS in the early aftermath of the Great “Recession” was actually misleading. The peripheral bond spreads weren’t suggesting that the PIIGS were at risk that Germany and the Netherlands weren’t. They were the leading indication of where this problem would be exposed first (the weakest links).

In monetary terms, Germany and the Netherlands are much safer places and therefore they have been on the receiving end of the great unresolved imbalance. The far more uniform behavior of inflation given such disparate unemployment rates merely confirms the monetary nature of Europe’s economic problem, which is still enormous.

So instead of a European economy acting as a complete and healthy enough whole (pre-crisis) where production proceeds based on production concerns alone, it has become separated into islands of function and dysfunction by turn (post-crisis). The increase in liquidity or ECB balance sheet capacity has not changed these essential elements, because the output of central bank monetary policy is not functional economic money no matter how many textbooks write that it is. The monetary drag (represented by uniform inflation rates) is still too great of one overall so that in the south even sixteen straight quarters of linear “growth” hasn’t really improved the situation by all that much.

That means Mario Draghi and the ECB, encouraged by the media and mainstream, may well be preparing to end QE and perhaps like the Fed even “raise rates.” But they do so not on successful completion of monetary policy objectives, but more so on the grossly illegitimate and imaginary standard of “jobs saved.” In other words, Europe’s economy is not recovering, it just isn’t at the moment contracting (at least in linear terms, non-linear is another story).

Even if you wish to be charitable and give Europe’s central bank the benefit of the doubt in arresting the linear recession, it is still nothing like an end to the issue. What’s more, policymakers at least in Europe know it! Their focus on inflation (and bond rates) is not really about inflation, it is instead one means for checking monetary assumptions because in the real world we don’t really know what goes on for money. The media can talk about the end of slack and falling unemployment rates, but the real issue remains unresolved. Like everywhere else, Europe fails in this test. The problem remains even ten years later.

Stay In Touch