When the Mario Draghi as head of the ECB first introduced negative rates in early June 2014, his reasoning was very clear. As he said in the opening of his statement imposing NIRP on Europe, “Today, we decided on a combination of measures to provide additional monetary policy accommodation and to support lending to the real economy.” The way in which NIRP (the only policy rate which was and has been negative is the ECB deposit account, the so-called floor of the euro money corridor) is thought to support loan creation is by penalizing banks for holding idle reserves.

It’s a tough sell to banks, for sure, but even more in terms of common sense. Broadly speaking, it’s very difficult to encourage a positive financial outcome with only a stick. Conventional wisdom suggests that low funding rates are the carrot, the incentive to make money on the curve. But that’s not how banking works, as the real issue is always risk-adjusted return. If returns are low and risks perceived to be high, then funding costs almost don’t matter.

The imposition of NIRP was to try to make it matter, if in the wrong way. It’s a difficulty that Mario Draghi acknowledged almost two years after doing it. In March 2016, the ECB imposed a third addition to NIRP, bringing the deposit account rate down to -40 bps. Two months later, in a speech delivered in Frankfurt, the ECB chief said:

They [low interest rates] put pressure on the business model of financial institutions – banks, pension funds and insurance companies – by squeezing interest income. And this comes at a time when profitability is already weak, when the sector has to adjust to post-crisis deleveraging in the economy, and when rapid changes are taking place in regulation.

But why are interest rates (non-policy) so low in the first place? If NIRP isn’t working as sufficient penalty to get banks to overcome grave reservations in light of risk-adjusted returns, someone needs to answer for that. Draghi blamed a familiar central bank standby, resurrecting a middle 2000’s staple of Federal Reserve ideology.

There is a temptation to conclude that since very low rates generate these challenges, they are the problem. But they are not the problem. They are the symptom of an underlying problem, which is insufficient investment demand, across the world, to absorb all the savings available in the economy.

Mario Draghi actually said that Europe, as the rest of the world, is once more captured by a global savings glut or something like it. There is, in his view, insufficient “demand” so that investment might rise as all these savings are put finally to good use. Therefore, monetary policy must increase “aggregate demand” in whatever ways possible so as to normalize this harmful imbalance.

As is typical of central bankers, they have monetary factors all backward. In Draghi’s view, he starts with too much money in the form of savings. He even, like Ben Bernanke in 2006, references Baby Boomers saving for retirement as one possible cause! So what good is it, then, to create more “money”, as central bankers believe QE does, when there is already way too much savings?

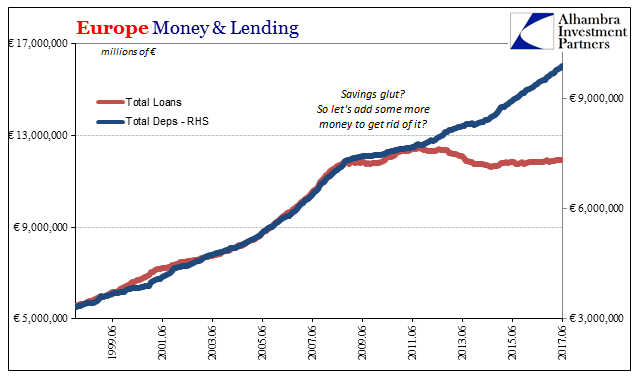

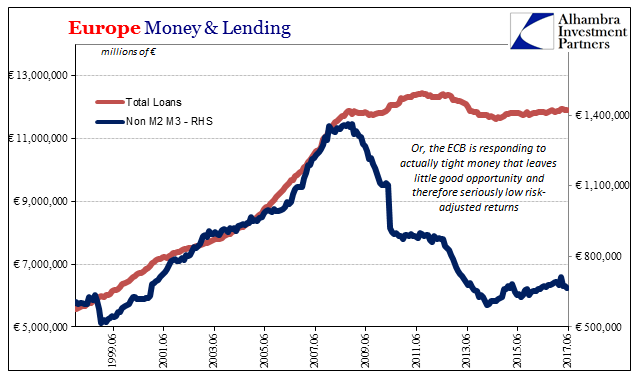

NIRP was created partly as an answer to that problem, to at least motivate bankers (through penalties) to do something productive (lending) with further excess “money.” It hasn’t worked at all, as lending in Europe is as low today as it was when NIRP first began, still considerably less than the peak reached more than five years ago now.

As is usual in these cases, Draghi starts with some piece of the truth. He is absolutely right to point out that low interest rates are a symptom, but of what? He says a savings glut whereas in all historical occurrences low rates always, always coincide with “tight money.” Milton Friedman’s interest fallacy is as Draghi describes.

Orthodox economics demands that we recognize what central banks do especially under LSAP’s (large scale asset purchases, commonly known as QE) as money. It is here where the confusion begins.

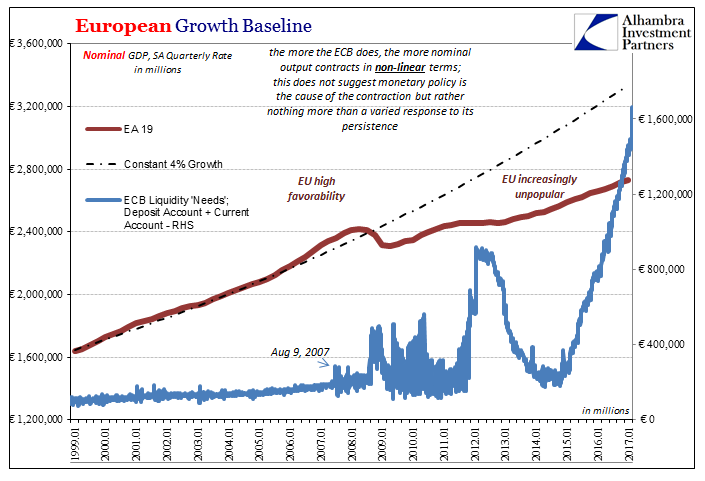

The modern monetary system isn’t so straightforward, depending instead on bank balance sheet factors for functional monetary conditions. The ECB can create all the reserves it wants, and it has, more than €1.75 trillion and counting since 2014, and even penalize institutions who hold them, but if banks still refuse to do anything with them are they really money? The answer is a straightforward no. They are just one input on the liability side among many (and not even an important one, as Europe’s track of total loans demonstrates).

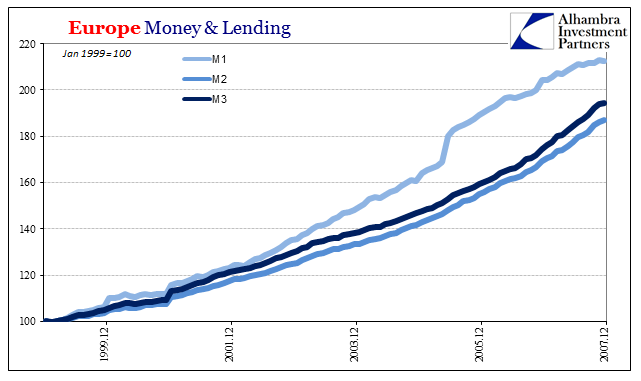

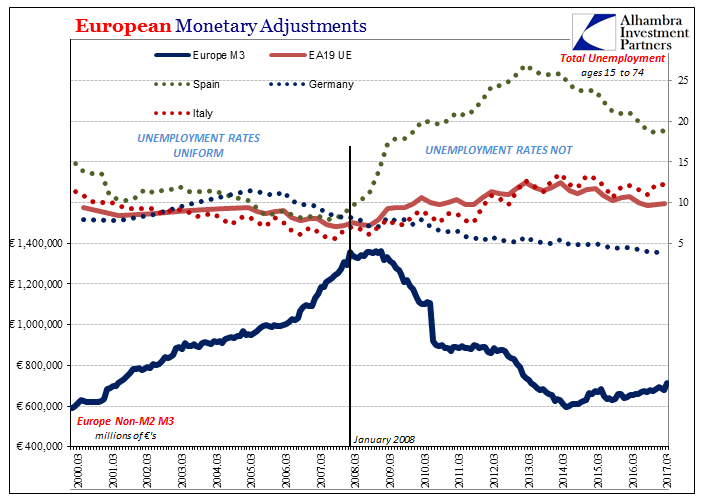

The more esoteric monetary statistics and aggregates bear that out. As in both the United States as well as Japan, the more balance sheet intensive, interbank forms of money (M3; though I caution to look upon M3 in Europe as a complete picture of these other monetary forms; for our purposes here, it’s close enough) have in the post-crisis period grown far more slowly than the traditional definitions which include everything that the central bank does in the form of reserves.

Europe may be the exception in that M1 expanded much faster in the pre-crisis period (euro adoption), but after 2008 it doesn’t matter what happens in deposit forms since the more modern definitions grow unenthusiastically no matter what the ECB does. In relation to lending, which is what much of this is supposed to be about, there is a clear one with the non-M2 M3 components far more than with M1 and the ECB’s bank reserves (NIRP or not).

In the broadest terms (which still aren’t broad enough), there is no glut in savings or otherwise. Monetary constraint has contributed in unseen ways in the real economy to lack of opportunity, and therefore the hoarding (liquidity preferences) of what money is available. That is why even at -40 bps in “yield” through NIRP, banks in Europe are today holding nearly €600 billion in that deposit account. The balance has grown steadily ever since the first negative rate was imposed in 2014.

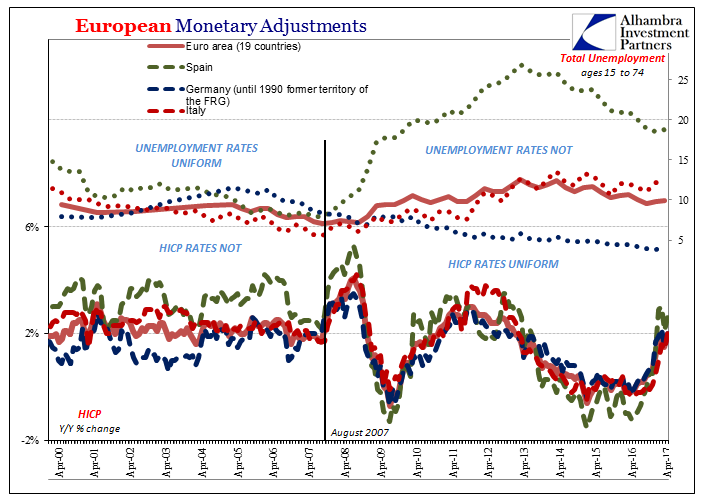

Furthermore, we know monetary conditions are “tight” in the real economy through bond rates but also inflation. No matter what the ECB has done, inflation has remained below its official, explicit inflation target for 53 out of the past 54 months – and the one month where Europe’s HICP rate actually registered 2% (barely in February after a 90% year-over-year gain in Brent) was due to oil prices not bank reserves, NIRP, or monetary policy.

As noted this morning, there is also one more economic check of these assumptions. In the case of unemployment rates throughout the Continent, the sudden appearance of dramatically different employment conditions in each of the Euro Area’s constituent countries further confirms this tight money condition and the liquidity preferences that accompany it. The same thing has happened in the United States, only not broken down by geography. The participation problem is the US economy’s similar answer to dealing with the same monetary deficiency.

Tighter money favors in the real economy as in the bond market lower (perceived) risks by location, standing, or whatever possible economic parameter. Germany can expand output relative to Spain, when in reality both are being constrained only one vastly more than the other.

Mario Draghi, as Ben Bernanke before him, created the global savings glut as a way to try to explain what is really a direct contradiction. In truth, there is no need to resort to circular reasoning and ridiculous convolution to understand what is instead straightforward and historically established. Once you set aside the idea that bank reserves are money and NIRP is a “stimulus” to use it, then all the “tight money” signals gathered and remaining throughout Europe and the rest of the world can be appreciated for what they are.

Stay In Touch