In April 2011, the European Central Bank’s staff and Governing Council were all optimistic. They had suffered through the panic and Great “Recession” and then the relapse in 2010 that birthed the term PIIGS. Despite all that and with considerable effort on their part (especially the purchasing of bonds), they thought there was reason to be quite optimistic.

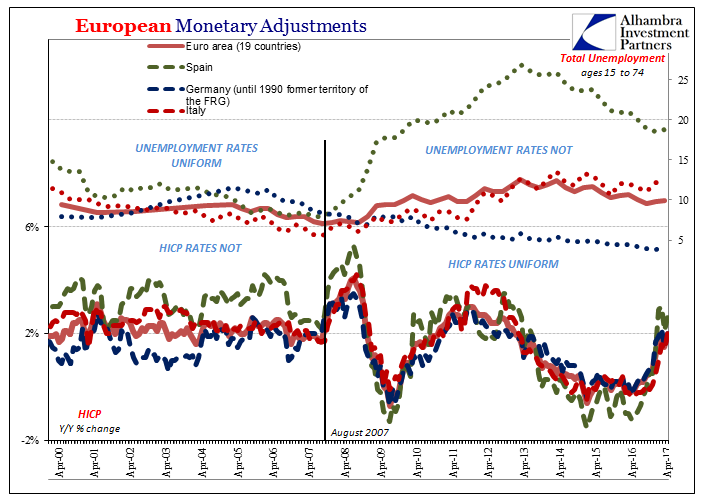

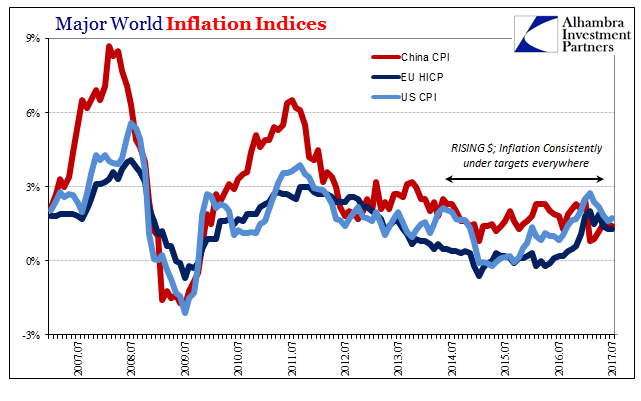

Inflation by early 2011 had returned with a roar. In March 2011, the EU’s HICP (inflation) rate had moved back above 3% after being negative for several months in the summer and autumn of 2009. To policymakers, it was exactly what they were waiting for.

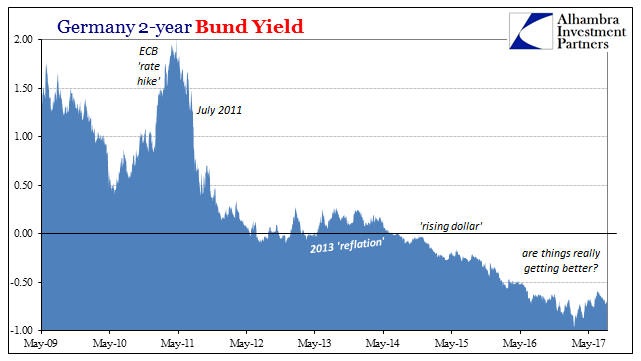

With that inflation tailwind and all their econometric models assessing the economy in the most positive terms, the ECB on April 6, 2011, voted for a “rate hike.” The monetary corridor would be raised by 25 bps, taking the MRO midpoint from 1% to 1.25%. It was widely expected that it would be just the first in a series to begin the process of normalization.

Europe’s central bank did follow it up with a second “rate hike” in early July 2011. At the press conference announcing the latter policy adjustment, ECB President Jean-Claude Trichet was practically gushing:

The further adjustment of the current accommodative monetary policy stance is warranted in the light of upside risks to price stability. The underlying pace of monetary expansion is continuing to gradually recover, while monetary liquidity remains ample with the potential to accommodate price pressures in the euro area.

He only noted in passing that “recent economic data indicate some deceleration in the pace of economic growth in the second quarter of 2011.” It was the same downside risks over financial uncertainty that Europe’s policymakers had been combatting since 2007. They were very confident that they had been fully successful dealt with.

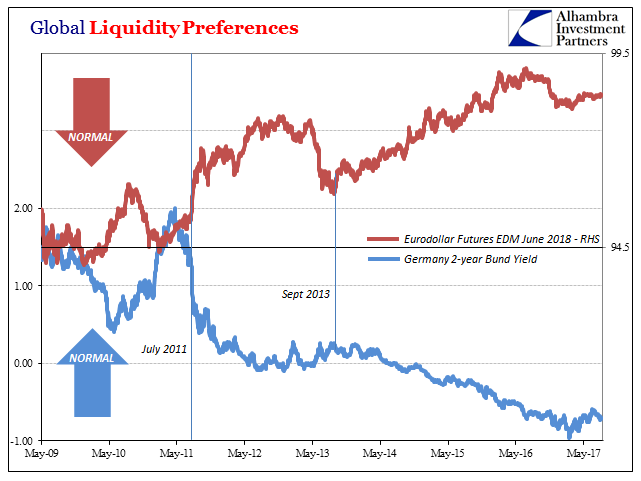

Of course, none of that was true. In a matter of just weeks, Europe and the rest of the global monetary system would be embroiled in a second irregularity almost equal in scale and intensity to the first. There was no ample liquidity, for the defining characteristic of this next crisis was the same as the earlier one that brought on full-scale (interbank) panic.

Europe’s economy would very shortly suffer, too. While the entire global economy fell into a downturn, in Europe it would experience another outright contraction. This re-recession was devastating especially to the most vulnerable nations within the euro bloc. None of them have yet to recover; many if not all of them remain so very far from even thinking that way.

And yet, this was not the first time the ECB had done this!

In July 2008, Europe’s central bank had also raised its corridor rates by 25 bps, right into the teeth of that first worldwide monetary event. At the press conference held accompanying this earlier policy “tightening”, Trichet again got it all wrong:

Moreover, continued very vigorous money and credit growth and the absence thus far of significant constraints on bank loan supply in a context of ongoing financial market tensions confirm our assessment of upside risks to price stability over the medium term.

How in the world does a central bank do this twice in three years? The answer to that question is the same that must be kept in mind when listening to Mario Draghi, Trichet’s successor, talk about Europe in the same terms in 2017. They really don’t know what they are doing.

It might be tempting to credit or blame the global crisis in 2008 or the reflaring of it in 2011 on the ECB’s “tightening.” It is the orthodox instinct, after all, to infer monetary policy in causing almost anything that happens after it. But that is assigning far too much consideration to what is almost entirely irrelevant.

What is instructive about both episodes is not what the ECB was doing, but rather what its policy direction was in contrast to others, especially the Federal Reserve. By July 2008, the Fed was fully engaged with all sorts of liquidity issues and new programs designed (badly) to meet them. Likewise, in 2011, the US central bank was still conducting its second round of QE when the ECB voted that first corridor rise.

And yet, despite completely opposite monetary policies, the condition of the monetary system in both as well as the economic responses to them was the same each time – some degree of permanent downturn. Monetary policy in either place didn’t matter, as the unifying factor was global money that neither official regime officially acknowledged (or acknowledges now). We are full circle again not because monetary policies work but because they don’t.

This time, the US Fed is already “tightening” while in Europe QE is ongoing. And still in each the results are the same. Unlike either early 2008 or middle 2011, neither can find inflation this time.

Mario Draghi is very likely about to unleash his inner Trichet, and the media in particular cannot wait for that to happen. The anticipation of it is entirely palpable because of what they think it means for this whole slow-motion political rebellion. Populist angst and outbreak is in response to these “elites” constantly being wrong not about the finer policy details but the big things that matter. The “establishment” badly wishes to find proof of populism’s illegitimacy, to go back to a time when the people took officials’ words at face value.

As I wrote earlier today (subscription required):

Even if that does trigger the next BOND ROUT!!! it doesn’t change this situation. Mario Draghi is always optimistic about Europe, and always has the best things to say about QE. Like the Fed, however, he wants to get out of QE because nothing has changed and nothing will. The pause or end of the “rising dollar” didn’t lead to recovery in Europe, just like it didn’t here; it only has calmed the global economy sufficiently for him to plausibly justify QE’s removal.

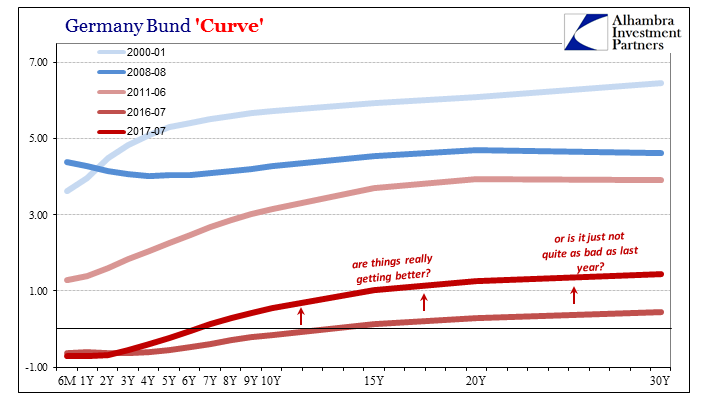

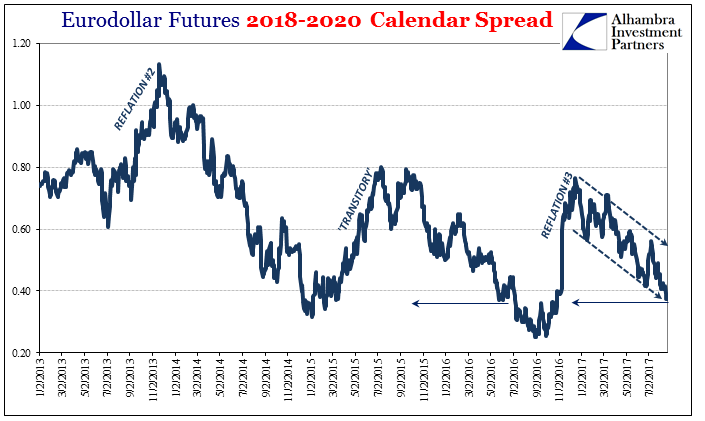

One need only review curves to see this in evidence. Many (there as well as here) are as low and flat as they were last summer when the world seemed headed only for very ugly things. And unlike either 2008 or 2011, the world’s central banks have only the promise of future inflation this time to justify the same outlook.

To say there is a lot of skepticism would be an understatement. That such doubt is warranted can no longer be questioned, at least not rationally.

Stay In Touch