In 1871, W. Stanley Jevons in the preface to his book The Theory of Political Economy writes of a fundamental human issue with Economics. He makes a distinction between it and other sciences which do not suffer, as he said a century and a half ago, “the weight of authority.” Finding such words from so long ago from when Economics was a relatively new endeavor is as illuminating as it is frightening.

From then to now, how can we call this is a science when its tendencies from almost the beginning seek to quell further investigation?

I believe it is generally supposed that Adam Smith laid the foundations of this science; that Malthus, Anderson, and Senior added important doctrines; that Ricardo systematised the whole; and, finally, that Mr. J. S. Mill filled in the details and completely expounded this branch of knowledge. Mr. Mill appears to have had a similar notion; for he distinctly asserts that there was nothing in the Laws of Value which remained for himself or any future writer to clear up. Doubtless it is difficult to help feeling that opinions adopted and confirmed by such eminent men have much weight of probability in their favour. Yet, in the other sciences this weight of authority has not been allowed to restrict the free examination of new opinions and theories; and it has often been ultimately proved that authority was on the wrong side. [emphasis added]

In Economics, authority trumps all else. The issue for science is supposed to be one of evidence, primarily. Unlike other sciences, what in Economics passes for observation or might fit within Karl Popper’s definitions? We have at best incomplete statistics augmented by imperfect market prices, where the relation between the economy reported on by the statistics and those prices remains mostly a hidden mystery.

Under these circumstances, why not just revert to authority? If Keynes said the world was supposed to do X when given Y, and instead does Z, the default position for many if not the vast majority of Economists is to go back to Y rather than X. Keynes has to be right, it is assumed, not because of any recent evidence but because we are still talking about Keynes.

The point is not to get into doctrinaire argument about which brand of Economics is less useful than another, but to follow the general theme to its furthest conclusions. None of these Economists who have filled all the official jobs from one end of the Earth to the other have been able to solve the lost decade. Not one. And in so failing they have often been reduced to redefining the standard for success.

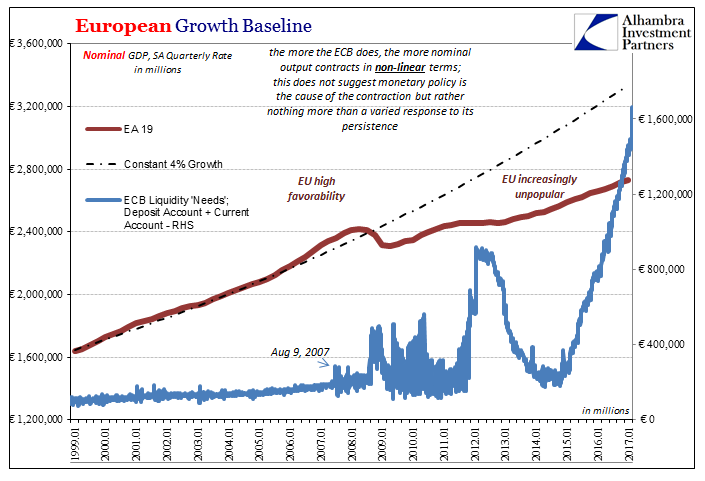

They all started out promising recovery under terms that would have been generally accepted. In the ten years since the first eruption of (monetary) crisis, the word has undergone a gradual but gigantic shift. It has led to growing discontent and really mistrust.

This will in some ways reach another crescendo this week in Wyoming. Central bankers are gathering at Jackson Hole on the invitation of the Kansas City Federal Reserve branch to discuss reframing recovery. Last year’s gathering was perhaps more auspicious (and less breathless media coverage) for what it was lacking – clarity and understanding. This year, Economists are going to say recovery has been reached without defining what they truly mean. They seek to avoid that part at all costs.

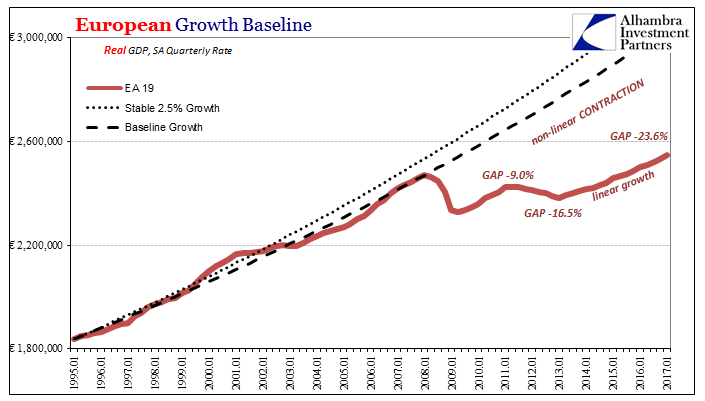

Most people don’t follow the economic statistics all that closely. They may be aware on a quarterly basis that GDP has been positive for some time, no further negative numbers to put in bright typeface what they experience. In Europe, it has been seventeen quarters since the last linear contraction, so recovery must be the condition – so says the weight of authority.

Mario Draghi is right now expected to be the main event. All the hype has been built up and managed on a “will he” or “won’t he” say that Europe has recovered, that QE has worked if belatedly (two and a half years already has alarm bells ringing).

But it is a lie, and most people know it. “They” keep telling us things are getting better, their grand schemes bearing righteous fruit, but most do not see it and certainly can’t find it. We know the extent of the dissonance in these raw terms by politics, the primal cousin to economics (small “e”) that has been intertwined within it from Day 1.

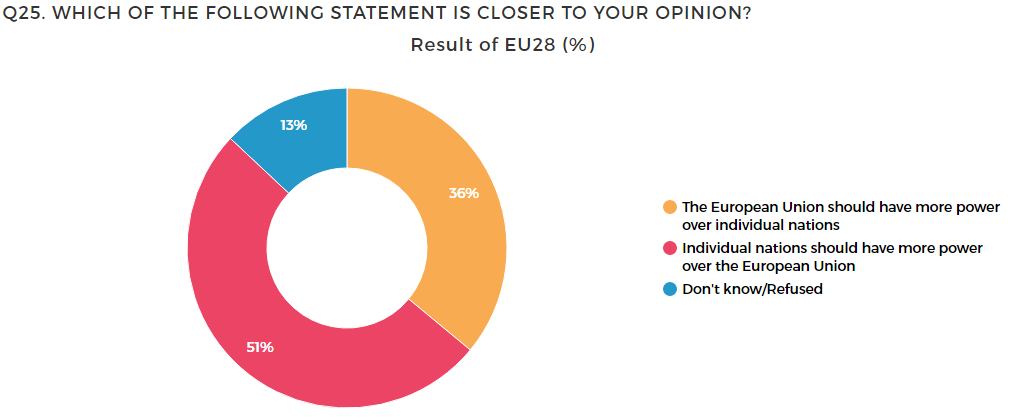

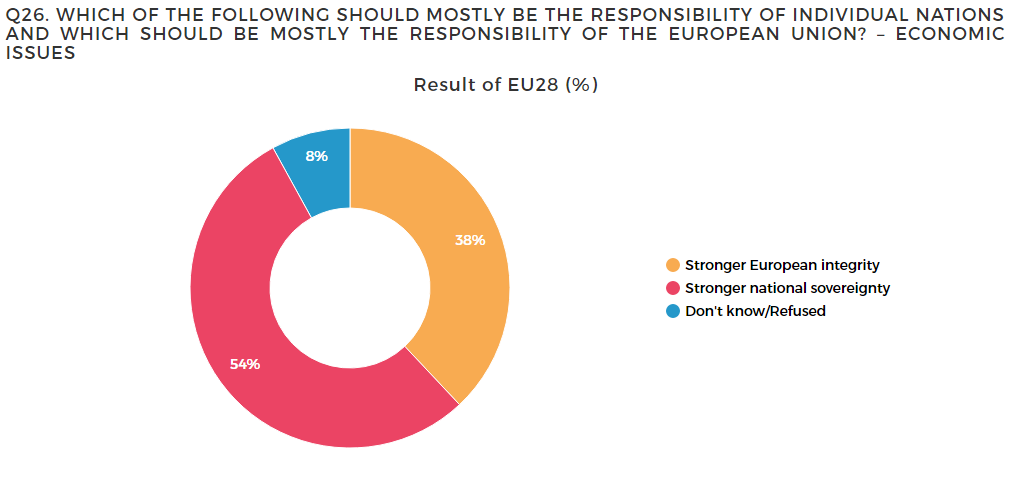

Hungary’s Századvég Foundation, a conservative think tank, has been conducting extensive surveys in the EU’s twenty-eight member states. Its Project28 has for the last two years surveyed 1,000 adults in every country (for a yearly sample of 28,000). The results for the 2017 survey were released early last month.

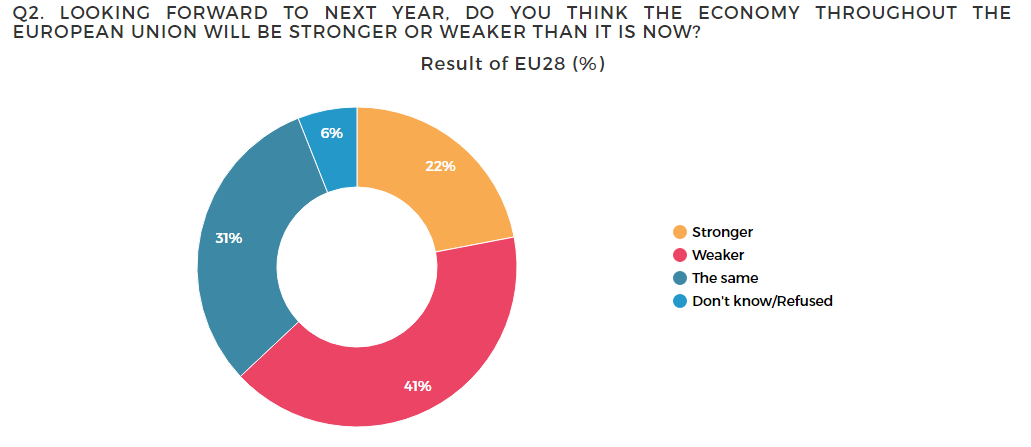

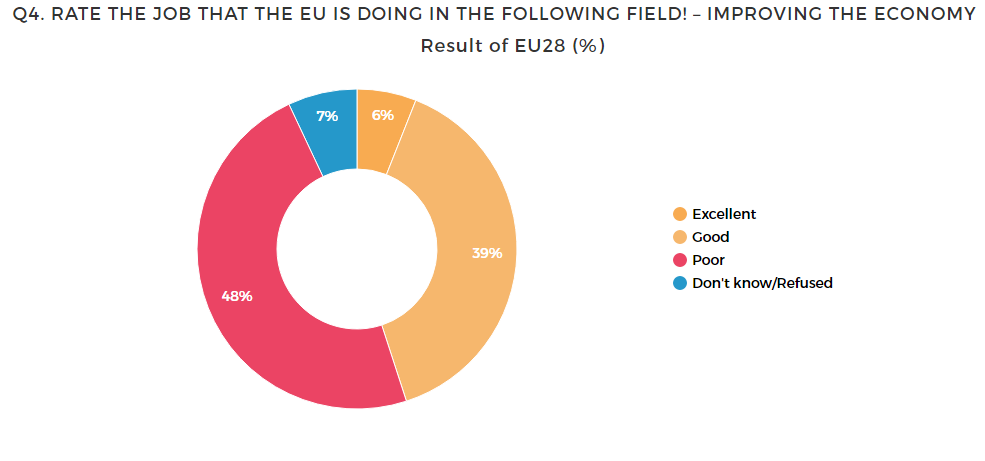

A large plurality (41%) of Europeans thinks the economy will be weaker next year no matter what Mario Draghi says this week (only 22% might be willing to agree with him). The results obviously differ by country, but break down along predictable lines. In Greece, 81% believe the EU is doing a poor job improving the economy, while 74% in Italy agree. In Poland and Hungary, by contrast, majorities believe the EU is doing a good or excellent job.

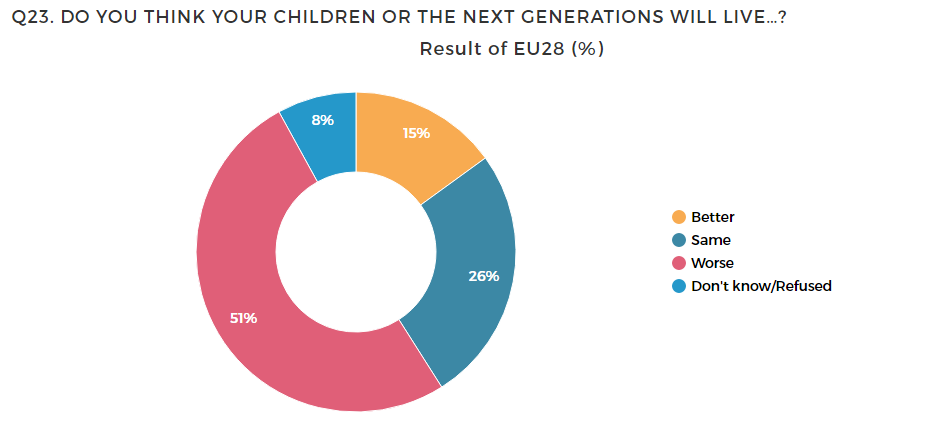

This pessimism is deeply entrenched, where a majority of Europeans (according to the survey) believe things will be worse for their children or grandchildren. Only 15% said it would be better, far less than those who either didn’t know or refused to answer the question. This is where the failure of economy because of Economics meets with politics. Hopelessness to this indicated degree is destabilizing.

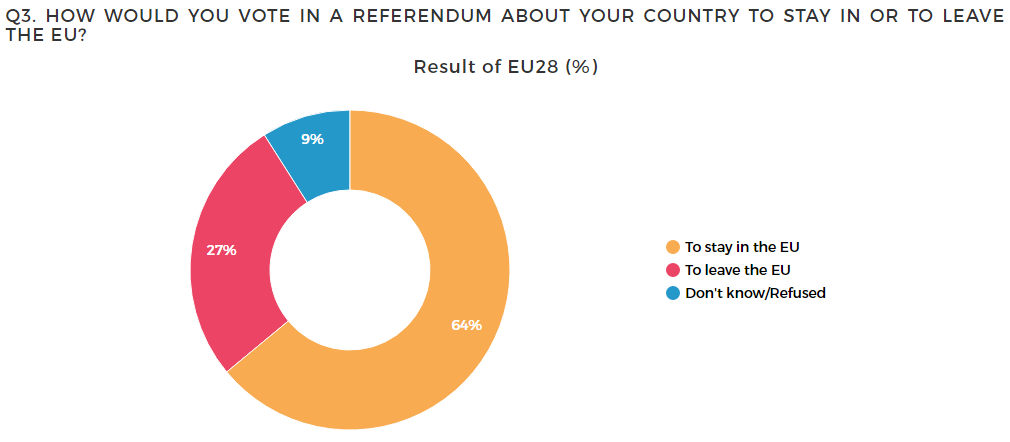

Despite all this, however, the survey finds surprising support for the EU project. A larger majority would in a referendum vote to stay in the EU as leave it. These results are found for the individual nations as well as in the aggregate.

Even though 81% of the Greeks surveyed thought the EU was doing a poor job on the economy, they still voiced support for it by 54% (stay) to 39% (leave). Only in the Czech Republic was there a larger proportion for leaving as staying (47% to 43%).

I think this dichotomy of opinion is interesting in a helpful sense of understanding something like Japanification. People are dissatisfied and increasingly distrust institutions and the “elites” who staff and run them. But they are not so dissatisfied so as to blindly wish to blow it all up and opt for truly radical changes; better the devil you know.

That’s ultimately what Japan’s trajectory was, where the people knew it was wrong but it periodically seemed to get better, or at least conditions were plausibly supportive of the possibility. Nothing ever goes in a straight line, and the same is true of depression. We too often think of economic depression only as the crash, which in reality is just the beginning.

The world economy grows just enough (at times) for people to want to give it one more chance, to perhaps tinker with the framework instead of starting from scratch. And it never really grows enough for that desire to stop and for politics to go back to whatever might count as normal. It is the worst case, numbness and acclimation to what truly is further and further from recovery or growth.

Mario Draghi will provide the weight of authority for some definition of recovery at Jackson Hole, and most Europeans will not believe him. They shouldn’t. But it’s also not bad enough right now for them to call for radical change. It is eurodollar-driven political paralysis, the emphasis for one lost decade to bleed already into a second.

Even the QE’s to some degree fall under this cultish existence, for trillions in money printing have to show up somewhere at some point. It can’t be that all the worst cases merge together; that the Fed [or ECB] could totally strike out like that, and the economy stuck without expansion for a decade and more. Who ever heard of an economy that just shrunk?

Unfortunately, we have been studying one for more than a quarter century, which only adds to the seeming impossibility of it all. We have known about Japan for all that time, so it can’t be that we are following that path being so aware of it. That might be, though, where a significant proportion of doubt has come from especially in inflation expectations unanchoring (as well as bond rates and eurodollar futures) because the Federal Reserve [and ECB] for all its posturing and assurances did exactly what the Bank of Japan did – and the results were exactly the same. We want to believe we aren’t Japan, and yet, we know on some level that we are.

Japanification was not banks or monetary policy, but a slow, methodical strangulation, the proverbial boiling frog who realizes the water’s temperature long before it’s too late but rationalizes it as a manageable if increasingly uncomfortable circumstance. There’s an abstract sense of the problem but not enough to motivate what might seem more drastic solutions to solve it; a sort of anxious apathy.

I think we depart the Japanese model in one important way, however. It leaves the future as increasingly binary; it will go on this way until it can’t because the weight of authority will deny there is any problem at all up until the very point that simmering discontent just blows up. Japanese authorities, apparently, can do that in Japan. The rest of the world is not Japan, merely following their economic trajectory. The political trajectory may end up being something very different.

Stay In Touch