The American banking system had been primarily a domestic one throughout its early development. Despite, or because of, the rapid growth in the later 19th century, banking was orientated almost entirely inward to finance the needs of that growth. But as a growing national as well as industrial power, the US adopted several measures early in the 20th century to entice domestic institutions into the foreign money trade.

The American banking system had been primarily a domestic one throughout its early development. Despite, or because of, the rapid growth in the later 19th century, banking was orientated almost entirely inward to finance the needs of that growth. But as a growing national as well as industrial power, the US adopted several measures early in the 20th century to entice domestic institutions into the foreign money trade.

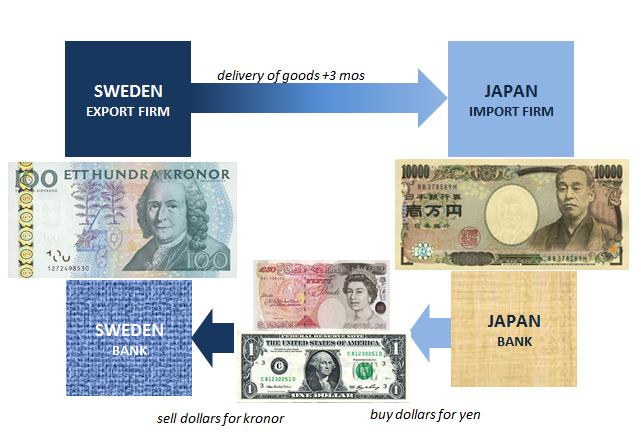

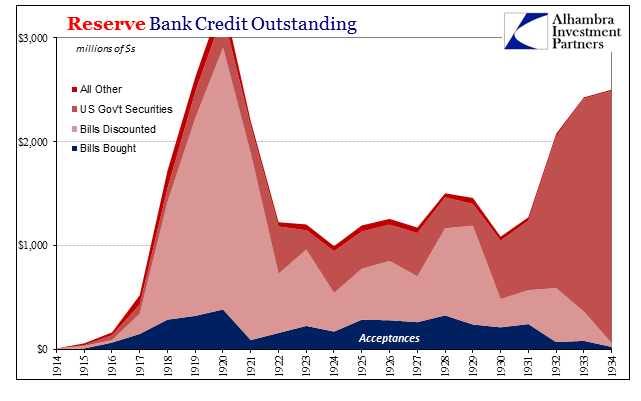

One of the first tasks of the new Federal Reserve central bank was to encourage a US dollar bankers’ acceptance market. Acceptances were a form of international money instrument, sort of a cashier’s check denominated in a common currency (primarily sterling given the UK’s dominion over much of the world and the British navy’s role in protecting commerce and trade). American authorities sought to compliment sterling acceptances with dollar acceptances so as to boost the trading power of US firms doing business abroad.

In the early days of the Fed, the institution would make a market in acceptances to such a degree that it was using them to manage total system seasonal flow (sort of like open market operations would later use UST’s to add or drain liquidity). Dollar acceptances flourished especially in the wake of gold inflows due to the WWI powers abandoning the gold standard that bolstered our currency’s international position.

Apart from those, the Fed also relaxed and removed restrictions so that US banks could begin to conduct more foreign business directly. In 1913, System regulations were changed so that National banks with $1 million in capital and surplus could establish foreign branches, subject to further approval by the Board in Washington. Only one bank chose to do so, however.

In 1916, the Federal Reserve Act was modified so that banks participating in syndicate could aggregate together the $1 million capital requirement (that was a lot of capital in those days), so long as the sole purpose of this agreement corporation, as it came to be called, was exclusively foreign banking. Only three were chartered by 1919.

In that year, Senator Walter Edge (R-NJ) sponsored a further amendment to the Federal Reserve Act that allowed for charter corporations to engage in international banking. These were called Edge Act corporations, or Edges, and for most of the next few decades they did very little and played a small role in further financial developments.

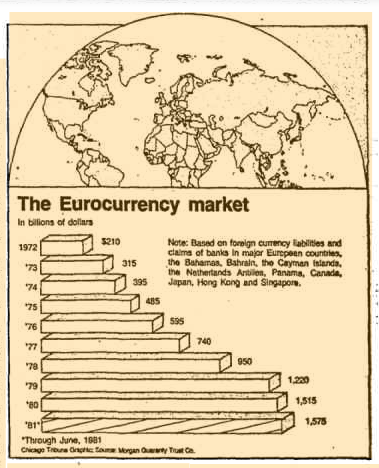

For anyone following the development of the eurodollar, it will come as no surprise that Edges suddenly became more popular in the 1960’s. Having been dormant or nearly so for forty years, there was a growing international money business where the Edge Act could finally be applied to great benefit. There were, according to the Federal Reserve Board, 38 Edges and agreement corporations in existence in 1964 (many chartered during the 1950’s) and 122 by 1976 (with $12 billion in total assets).

The benefit of any domestic bank sponsoring an Edge Act or agreement corporation was that it could conduct overseas bank business (largely) free of domestic regulations. So long as any transaction was identifiable as being international, any deposit liabilities that might be incurred would not be subject to US reserve requirements. It fit the eurodollar system’s evolving nature as giving domestic institutions an entry into it.

Having developed a window into this offshore monetary regime, several developments in the early 1980’s were crucial to opening the door for more comprehensive progression. In December 1981, eurodollar futures were introduced in Chicago at the old Mercantile Exchange. Also in December 1981, International Banking Facilities (IBF) were created in domestic law.

Taking the latter first, IBF’s allowed banks to conduct their foreign business in consolidated fashion, if not via consolidated books. In other words, banks using Edges before 1981 had to have separate offshore quarters for their subsidiary. They had to be true foreign banks with only domestic ownership. It had led to the “brassplate” offices in the Caymans, where New York or Chicago banks would have to “operate” their foreign subsidiaries in those foreign locations using nothing more than a brassplate name on an office door and a single employee with a phone connection to the home trading/funding desk.

The IBF eliminated the cumbersome nature of the farce by allowing the domestic bank to quarter its foreign sub in its domestic offices; so long as the IBF kept separate books and maintained its solely offshore business nature. The operational efficiency as well as an added tax incentive (IBF income would be excluded from federal as well as some state taxes) meant US banks could more completely build out their dollar-eurodollar connections.

As FRBNY describes them:

IBFs enable institutions operating in the U.S. to compete more effectively for foreign-source deposit and loan business in the Eurocurrency markets abroad.

It was one of those cosmic coincidences that the tax and banking codes were changed at the same time eurodollar futures began trading. To say that there was enormous demand for them risks dramatic understatement. There are stories of traders camping out the night before the market was to open as if a scene at an Apple Store in 2007 during the iPhone introduction. It was quickly the largest trading floor at the CME for a reason.

Eurodollar futures are not money, instead an obligation related to hypothetical delivery of money. They were the first cash settled contract. Before then, futures positions were settled at maturity by physical delivery. It was the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, after all, where physical commodities had dominated its history (think Midwest agriculture and livestock moving eastward from the interior). But financial contracts like Treasury futures had by the 1970’s begun to outshine these traditional markets.

Cash settlement simply means that at expiration the two parties exchange only the difference in value of the contract from either when it was first bought or when it was last marked to market; there is no delivery of the underlying obligation. It makes for an incredibly efficient hedging vehicle.

For eurodollar futures, that’s a pretty big deal even for banks, companies, and funds in Chicago. The contract states it is for delivery of a 3-month, $1 million eurodollar interbank deposit to pay 3-month LIBOR. The price of the contract is settled as 100 points minus the LIBOR rate. That is why the futures price is quoted as some number less than 100.

The purpose of this market was from the start to hedge funding obligations obtained elsewhere, including but certainly not limited to eurodollar deposits. Thus, the coincidence with IBF’s was fortuitous from the introverted perspective of the eurodollar system. Because it was a deep and liquid market, the deepest in the world, banks would be able to hedge their growing appetite for participation in global offshore “dollars” of all other kinds. It is essentially a barometer for the cost of comprehensive funding in this global money.

The price itself does not give us the exact market expectation for what that cost might be in the future. There are, as always, formulas that have been developed if you so desire to calculate what X price today measures for Y LIBOR tomorrow. I think that misses the point in the same way a lot of academic finance tries to pinpoint the color of bark on individual trees so as to often miss the forest. It’s a faux precision that becomes too often the exclusive focus of inquiry.

What eurodollar futures tell us is today’s market’s expectation for money conditions in the future. They don’t tell us exactly what the 3-month LIBOR rate will be when the June 2018 contract is settled on the third Wednesday of next June.

And they don’t tell us what most people seem to think they do (of those who have ever heard of eurodollars or eurodollar futures). Conventionally speaking, a high eurodollar futures price (meaning closer to 100, further meaning current expectations for a relatively low LIBOR rate at contract expiration) is not suggestive of “stimulus.” As a deep and liquid pool, eurodollar futures are a suggestion of liquidity preferences.

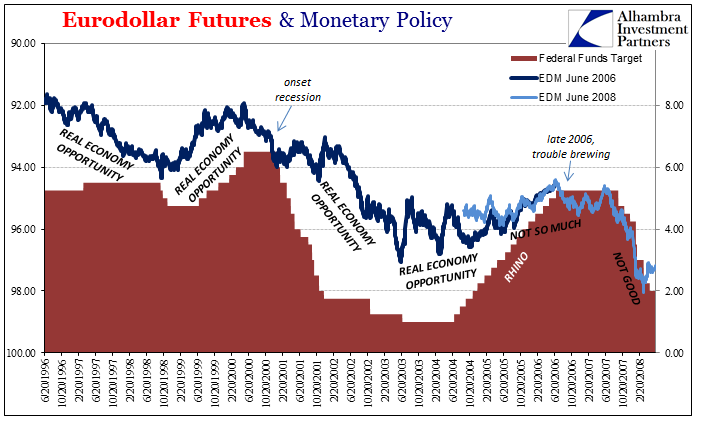

I’ve written in the past the FOMC’s tortured history with eurodollar futures, especially over the last ten years. The reason for that is simple; policymakers have it backward. They believe eurodollar futures are nothing more than what they say they are. In reality, eurodollar futures are not obligated to follow the script policymakers would prefer, and often demand. Starting in late 2006, eurodollar futures began to suggest what was wrong when instead the FOMC debated all the ways that couldn’t possibly be true (obviously, it was).

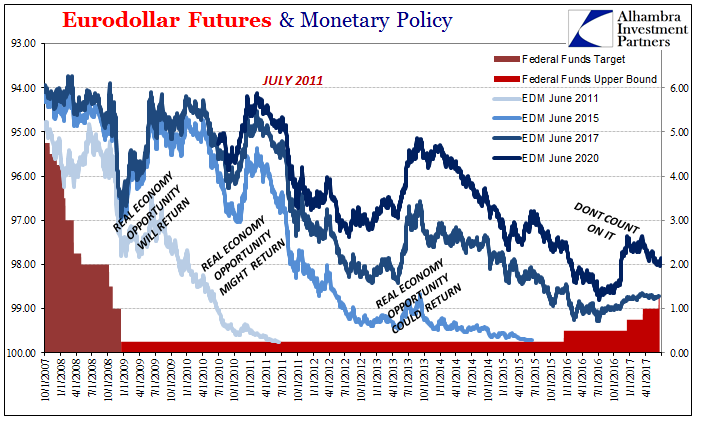

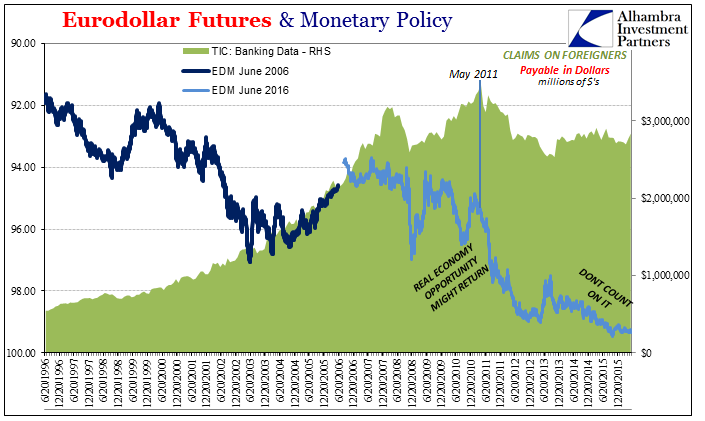

What eurodollar futures have indicated since 2007 is the state of the world in which monetary policy would have no choice but to react to. The final break in 2011 is the dominant feature, when at that time policymakers were modeling their exit. Eurodollar futures instead traded into what the massive (“unexpected”) illiquidity of that year might mean for global money and economy (nothing good, which is why prices apart from the brief 2013 and 2016 “reflations” have tended to rise).

It is akin to Milton Friedman’s interest rate fallacy, but in eurodollar funding. We often think of illiquidity in terms of money rates as being what LIBOR did in 2008 – to surge upward. Eurodollar futures, even though tied to LIBOR, did not do that during the panic, nor in the follow-up near-panic of 2011. They traded as what illiquidity would mean for the future – the results of panic rather than the panic itself. Prices relate to opportunity in the real economy

That is ultimately what eurodollar futures have been hedging for going on forty years now. It is barometer not of the cost of economic money, but the cost of interbank money as a consequence of economic monetary circumstances. If the economy is bad, opportunity is costly (adjusted for risk), meaning that the easy and riskless is the only option. It is easy to find money to do nothing rather than being demanded by firms in competition for funding to do real economy stuff.

We have been told that money rates are tied to the supply of funds when in fact it is almost always the demand for them. Eurodollar futures in “normal” times were often lower (in price), even when the eurodollar system was growing geometrically. Now that the funding system is not growing or much at all, futures prices are high/curves are low. This is the interest rate fallacy carried out here.

If you obtain eurodollar funding in whatever format on a short-term basis and are worried that rates will rise, you can effectively and efficiently hedge with eurodollar futures. If everyone believes the same thing at the same time, eurodollar futures will fall in price. Thus, if eurodollar futures do not fall in price and instead rise, what is the market hedging for/against? At or near ZIRP it can’t be for negative nominal rates, thus it is for fewer who believe that rates will actually rise or by a significant amount during the course of the contract.

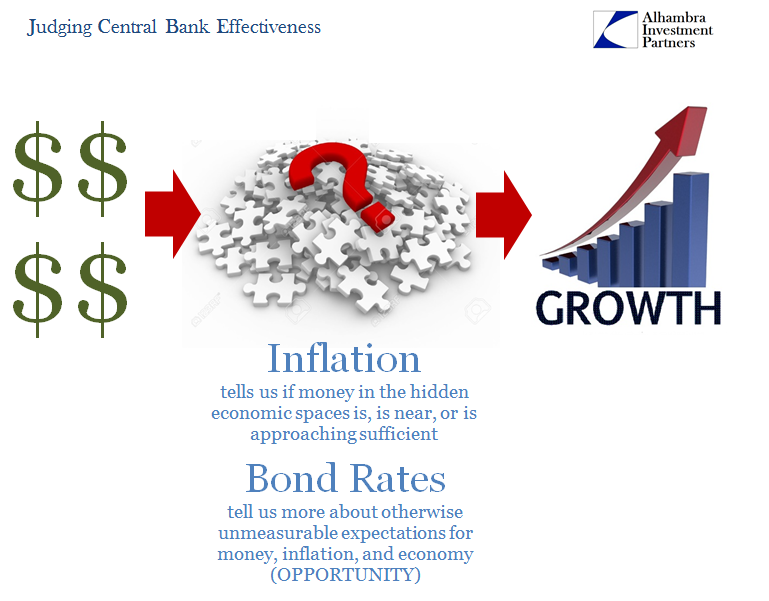

It describes where we are now and also how we got here. Like bond rates and inflation, eurodollar futures are a window into the hidden spaces where money and economy mix. Tight money conditions in the real economy are eurodollar positive (price) just as bond market positive (price).

This most crucial market has been indicating, for the most part, since 2006 money conditions in the real economy have been tightening. Federal Reserve officials in all that time refused to believe it, even though we have seen a full-scale global panic (not “unexpected”), nearly a second one not long after, then further distress more recently that though it was pointed toward offshore places was severe enough to nearly knock the US economy into recession.

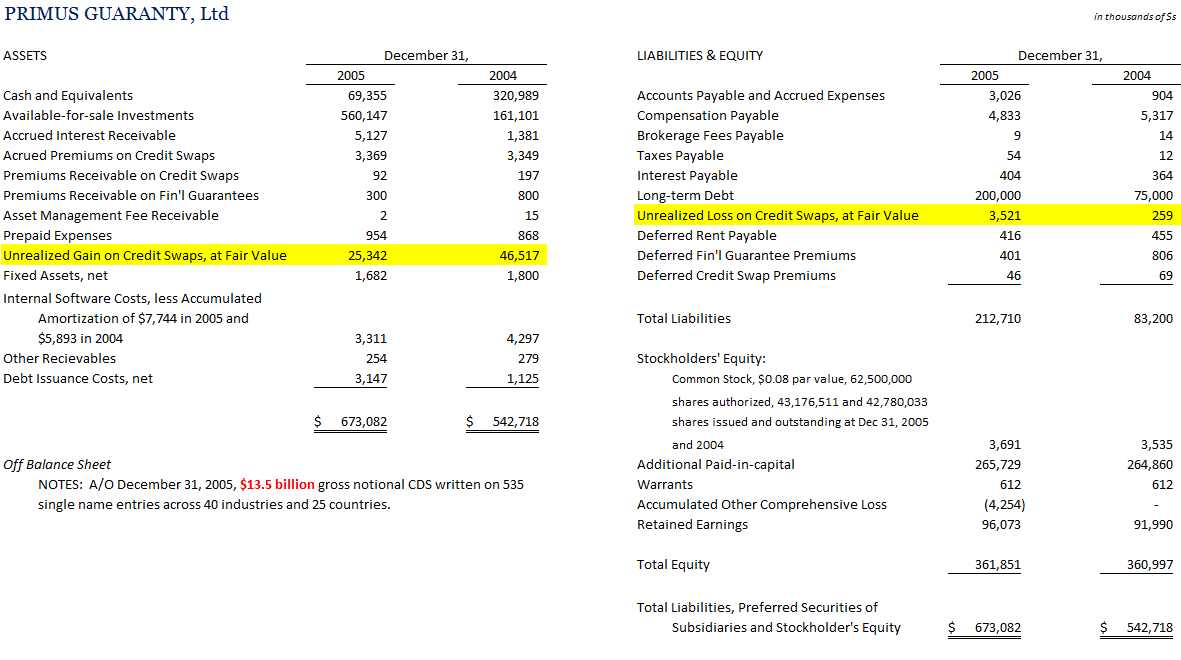

The downside of a “dollar” as a opposed to a dollar is that so much is now unobservable in the form of bank activities that never see the light of day (again, the bank at the center). Since we cannot even define a wholesale “dollar” we cannot think to even attempt its measure as it amounts to chasing a phantom.

A Brief History of Money, Part 1; Part 2; Part 3

We Know How This Ends, Part 1; Part 2

Understanding Eurodollars, Part 1, Part 2, Part 3

There were two major evolutions in money and banking that seem to fall outside the orthodox narrative. The first was a shift of reserves and bank limitations from the liability side to the asset side. The second was the rise of interbank markets, ledger money, as a source of funding rather than required reserve balancing; replacing the old deposit/loan multiplier model.

Far More Important What Is Not There Than What Is

For the most part, the concept of leverage is straightforward and intuitive. In physics, a lever is something that multiplies force to gain mechanical advantage. That is why the word was transported to finance as it means to multiply the effort of a small capital base. The “mechanical” force applied in the form of financial leverage used to be borrowed money or currency, but in the modern wholesale format the multiplication attains not only different forms but also added dimensions.

Of Modern Money And Multipliers

My purpose here is not to get too far down the rabbit hole, but hopefully far enough that you get a sense or at least a taste for this stuff and more so why it all exists to the degree it does. From that, the issue of truly modern money can be revealed. It all starts with accounting.

It’s the antithesis of the pre-crisis eurodollar system, where then these institutions believed no risk was too great because there would only be reward, but today global banking has been turned totally around to all risk with no reward.

If You Believe There Was Too Much Money During The Monetary Panic, Then Why Not Heroin

As I point out all far too frequently still, September – December 2008 was not the first period in which the federal funds rate had fallen below target in serious fashion for an extended length of time. The very first instance was August 10, 2007, which in many ways was a complete precursor of all these systemic discrepancies.

Currency Elasticity Only Applies Where There Is Currency

And that is the relevant point to our conditions right now. The money markets seem to follow policy decision only under benign conditions. Past some unknowable threshold, money markets become money market(S) with the Fed strictly powerless to enforce any kind of order and restorative measures to bring them all back into singular and seamless function. That makes its primary job of lender of last resort fully indefensible and untenable, which explains a great deal as to why we are where we are.

You can appreciate the willingness of Chinese monetary authorities to incorporate this odd arrangement; before the 1990’s, China’s economy was a basket case of authoritarianism as well as unevenness. That uncertainty was the dominant view of the currency, as well. Thus, to peg CNY meant to do so credibly, and what better short cut than to “back” CNY by “dollars?”

Rough End of a Collateral Century (Added July 28, 2017)

What finally became perfectly clear (to those observing) in the 2008 crisis was that under extreme duress particularly related to collateral quality, such a shortage that may arise turns all collateral from tangible financial instruments used in obscure funding transactions into actual currency. In many vital ways, during the worst moments (highest fails), the practical situation of a theoretical repo was reversed; cash became the collateral for collateral as the currency.

Eurodollar Futures, The Verdict (added August 22, 2017)

Stay In Touch