Liquidity and more so liquidity preferences are vastly misunderstood for a whole host of reasons. A lot of it has to do with the dominant strains of Economics battling each other (saltwater vs. freshwater) over which statistical model fails less frequently. In shifting to mathematics and statistics, something great has been lost.

Economists don’t understand how an economy works; and that’s OK with them. Ever since Milton Friedman wrote of Positive Economics in the 1950’s, Economics has trended away from economy.

It’s understandable to some degree, though not entirely sympathetic. The real economy is an impenetrable mess. You simply cannot observe what goes on all day every day every year. Nor can you really, truly understand why things happen the way they do all over a dynamic system that doesn’t ever stand still.

Some aspects are easier to consider and close enough to observation so as to be able to make reasonable inferences. These are most often activities connected to markets and published prices. Market prices are observations after all, no matter how imperfect, as is what happens in terms of liquidity.

When we often think on the word, it is usually in a purely financial context. Companies like banks need it, however, for any number of reasons. The most profitable industrial behemoths sell commercial paper on a daily basis to fund receivables or any other working capital requirements, as do the otherwise most boring names in the S&P 500.

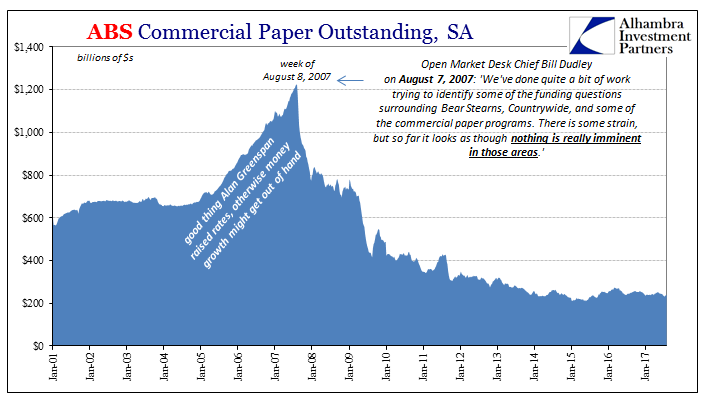

On October 7, 2008, the Federal Reserve created what was really a Special Purpose Vehicle, an off-balance sheet (sort of) entity funded by a loan from FRBNY (collateralized by the entity’s assets). The Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF) did what the name suggests; it bought commercial paper that the private liquidity market was avoiding during a systemic “dollar” run (commercial paper being one of those parts of modern eurodollar liquidity that doesn’t show up as traditional money in traditional money statistics).

We would expect to find out that firms like Bank of America or even Bank of Montreal were using it at that time for some measure of liquidity derived from the Federal Reserve. But the CPFF was providing monetary resources also to businesses like McDonald’s, Verizon, and Georgia Transmission Corp. When real economy companies like these are placed in such a position it could only be bad.

What do you do if you are the CFO of any of these firms who are placed in such a desperate situation that your company is at the mercy of the Federal Reserve’s demonstrably limited understanding and ability? ServiceMaster’s CFO Mark Peterson in 2008 contemporarily described the experience:

Ah, I don’t know, for those of you who have experienced an earthquake? You know some people say it’s a soul wrenching experience. Because you realize there’s a power out there that’s doing something that you have no control over whatsoever. And it’s massively moving everything. And that’s last week. Last week there was a monster that was unleashed.

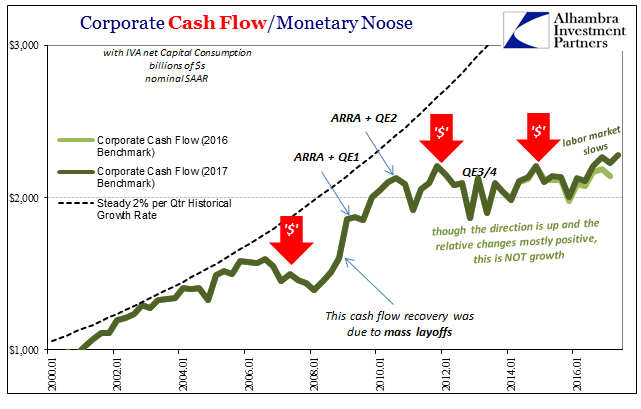

What you do is never put your business in any such situation ever again. You stress endlessly all the ways such micro failure might never be repeated. If you can’t trust banks for them having yanked away emergency credit lines (as so many businesses found out at the worst possible moments), commercial paper markets for reasons nobody could fathom (and most still can’t), or really any other typical standby approach (because they were always connected in some ways to banking, meaning eurodollar), then you hoard liquidity yourself. You self-write your own liquidity needs so that you won’t ever again be put into a situation facing the prospects of having to layoff workers not just because of a downturn but because there is no cash and no way to get it. No more monsters and no more lack of control.

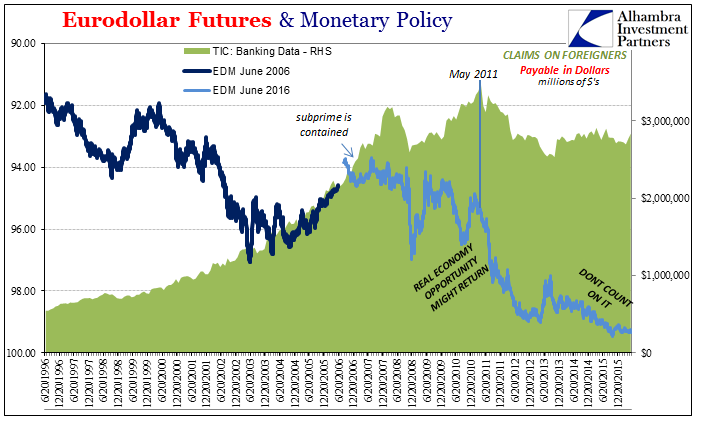

Those who could, which was almost all of them, went to the bond market after the panic was over to supplement what has otherwise been an internal liquidity movement. The monetary panic of 2008 was devastating in more than just cyclical fashion, as liquidity preferences are now structural; having been made all the more potent by the events in 2011 (as well as the “rising dollar”) that simply proved the mistrust as the correct approach.

The economic conditions of the slowdown thereafter are of this nature on both sides, both self-reinforcing; the more businesses hoard liquidity, the less they do in the real economy (do not expand labor and facilities, buy back shares instead); the less they do in the real economy, the less revenue and cash flow growth, therefore more pressure on liquidity preferences, and round and round it goes.

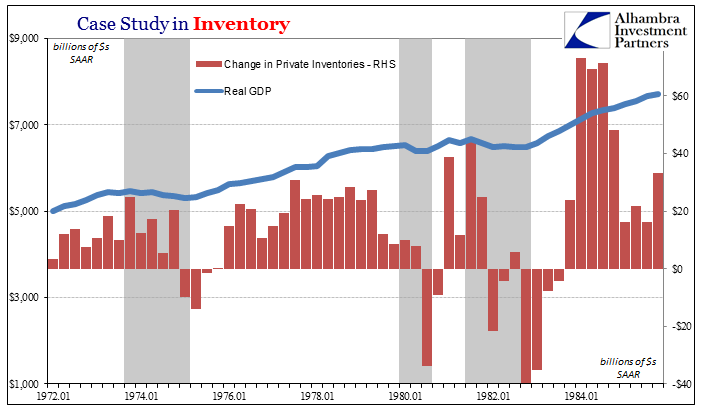

What may be a curious outgrowth of all this is the case of aggregate inventory especially in the near-recession of 2015-16. Along with layoffs, a downturn plus liquidity problems means inventory liquidation. One way to raise funds and lower cash needs surrounding a recession is to selloff whatever product you may have in hand at whatever realistic price you can achieve. It’s what has throughout history made recession recession.

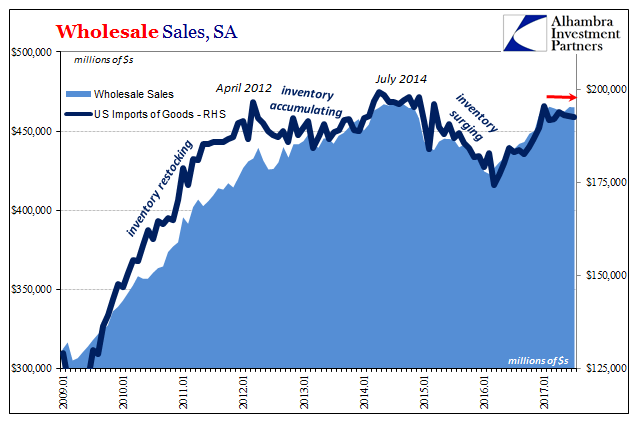

And it makes recovery. The truly desperate can only sell too much inventory, so that after the emergency has passed they have to restock even to get to minimum acceptable levels. It kickstarts one of the most basic cyclical upturn processes as producers are flooded with orders to rebuild that stock.

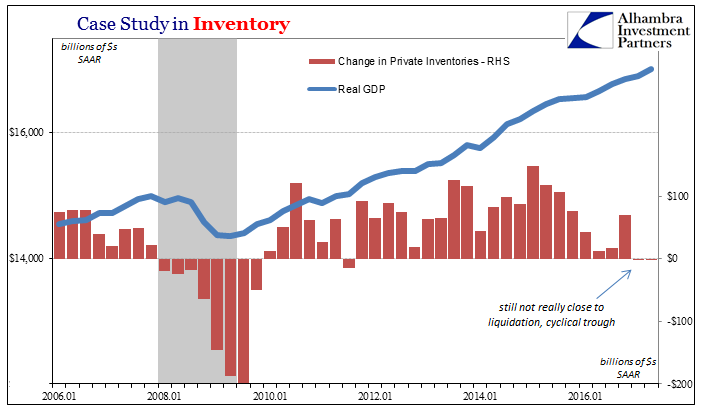

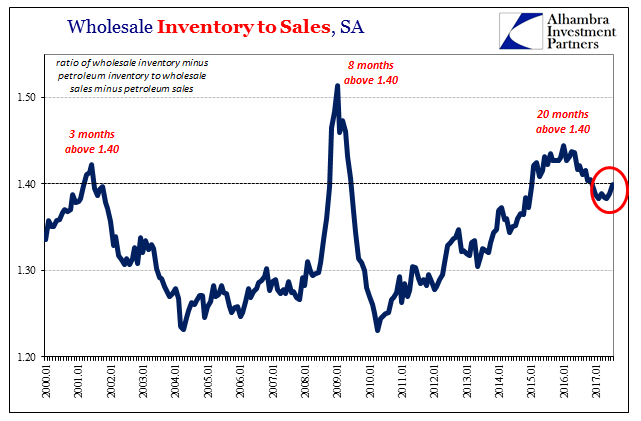

Faced with such a serious downturn starting in late 2014, however, US businesses never really came close to a liquidation (which in terms of GDP would have in all likelihood made Q4 2015 and Q1 2016 clearly negative). Inventory levels have instead remained historically elevated, especially on the wholesale level where US demand often meets foreign production (meaning global economic flow).

Going all the way back to 2015, I’ve often written that one potential explanation is Janet Yellen. By that I mean businesses use things like the Blue Chip Economic Survey of mainstream economists, who all get their data from the same place and look at it in the same way as Chairman Yellen, or whoever might be Fed Chairman at any given time, to forecast their business parameters. In the case of inventory, these surveys and really any talking head on TV or the internet pointed consistently to the positive case of the unemployment rate for why nothing would go wrong.

Very little was said about more negative prospects (such as why bonds were trading that way). Firms, though, were not immune to the real world as it turned in that direction. Thus, they started paring back inventory growth and ordering less across the whole supply chain out of prudence; if economists were right then there was little to be lost at perhaps just less than fully stocked; if they were wrong, then better to be hedged for what sales growth was suggesting.

Almost three years later, and a very serious downturn that did emerge in between, still no inventory liquidation. The same is true for the labor market; there was no wave or waves of mass layoffs. Could it be that liquidity preferences in the post-crisis period being self-written removed the recessionary liquidity pressures that might otherwise have pushed both inventory liquidation as well as mass layoffs? Like inventory, labor market data shows significantly slowed growth rather than the more dramatic.

It’s near impossible to say for sure. The evidence to this point suggests at least something like that for why inventory remains so high and also why there is so very little momentum in the real economy. If these further downside cyclical amplifiers were absent, cushioning somewhat the blow in 2015-16, so, too, the upside cyclical gravities are likewise missing. There is no need to rush production to restock since in the aggregate businesses remain overly stocked.

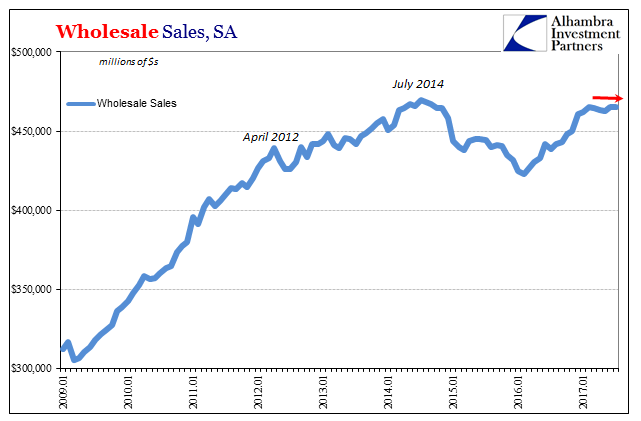

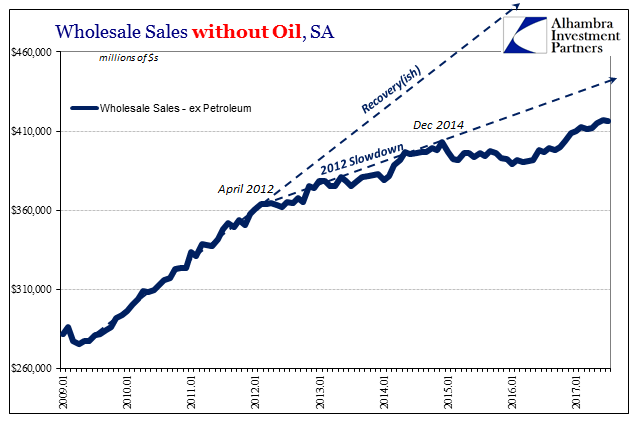

Wholesale sales and inventory data released today (for July 2017) add to the evidence for this theory. Sales growth has turned sluggish after a brief upturn more related to the price of oil than actual cyclical forces. The inventory-to-sales ratio (excluding petroleum) turned upward again, just the tiniest fraction shy of 1.40 and what is still a very extreme reading.

It might sound like progress, firms not subjected to inventory and liquidity pressure, but in truth if that is what has happened then it merely moves liquidity preferences in different directions. There are feedbacks to consider, such as how any firm caught holding so much inventory (which has to be financed even internally) might respond in other ways. In terms of the business cycle, inventory liquidation might actually be the least harmful reaction to a downturn especially in terms of time.

What we can say with reasonable certainty is that the inventory problem has been strung out over an especially long period for reasons that aren’t the usual cyclical matters. As with all things, it is certainly a product of a combination of uncommon factors. Liquidity preferences are, I believe, one of the more prominent among them. Tight money matters on timescales short and long.

Stay In Touch