The FOMC is widely expected to vote in favor of reducing the system’s balance sheet this week. The possibility has been called historic and momentous, though it may be for reasons that aren’t very kind to these central bankers. Having started to swell almost ten years ago, it’s a big deal only in that after so much time here they still are having these kinds of discussions.

My own view on the topic is the same as always; who cares? It’s certainly not the popular view but I believe it is the one that the evidence establishes as correct. The Fed is irrelevant; QE and balance sheet expansion had more to do with playing with people’s minds, and on their prejudices, than actual monetary anything. Therefore unwinding QE will very likely be more of the same – nothing.

Though it is of the minority opinion, it is a growing minority because again that’s what all the evidence shows. Even economists working at the Fed are starting to “get it.” It’s incredibly sad and perhaps somehow criminal it has taken so long, but how else can anyone reasonably explain $4.5 trillion and nothing to show for it? If the best you got is IOER, the intended and theorized floor that magically became a ceiling, you got nothing.

One such recent study was written and conceived by economist Stephen Williamson, the Vice President of Research at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (thanks to M. Simmons appropriately of Canada for finding it). To spoil the paper, he doesn’t believe QE made much positive contribution, either.

What’s encouraging, in that same frustrating way, is that Williamson is forced to look at QE from an outside perspective questioning the most basic monetary assumptions. By and large economists simply take bank reserves at face value, meaning an increase of them is treated as “money printing” or an increase in base money. It is that assumption more than any other that ruins everything thereafter.

Given the Fed’s monopoly on the supply of currency, and since private-sector bank deposits are imperfect substitutes for currency, if the Fed conducted an open market operation—say a swap of reserves for Treasury bills—then this would matter. That is, through movements in market interest rates and portfolio adjustments by financial institutions and consumers, the new reserves created by the open market purchase would end up as currency.

That is how the traditional monetary system used to work. Over time, however, it evolved into where the strange is commonplace and the utterly complex isn’t complex enough. It’s not at all surprising to regular readers of this space to find Williamson’s justification for questioning QE (except maybe to ask what took so long). Repo is a good place to start, but it’s only a start.

For example, on May 19, 2017, the one-month Treasury bill rate was 0.71 percent while IOER was 1.00 percent, so banks required a premium of 29 basis points to induce them to hold reserves rather than one-month T-bills. For what reasons are reserves inferior to T-bills? Basically, reserves can be held only by a restricted set of financial institutions, while T-bills are more widely held and are useful as collateral in financial transactions (e.g., repurchase agreements) in ways that reserves are not.

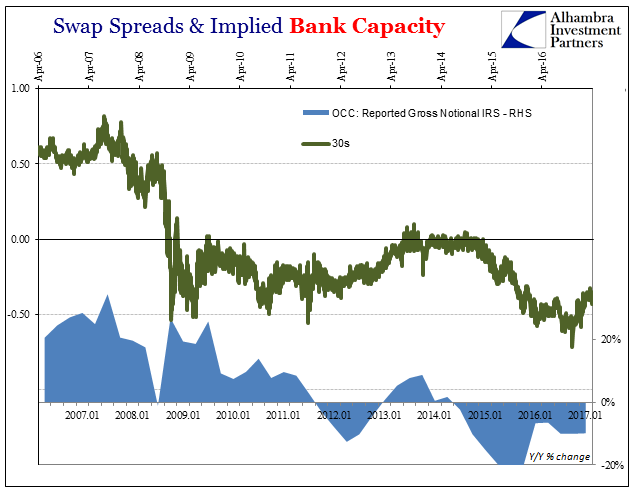

In other words, the monetary system is quite likely far more complex than the simple central bank example all, now most, economists assume for their models. If there are complexities to how especially in an interbank context reserves and money substitutes are treated and treated differently, then the whole vast world of the eurodollar system opens up to how easily QE could amount to so little (in far more than just repo; just wait until Williamson or others like him get to derivatives and balance sheet capacity).

Therefore, from financial intermediation theory, it is not clear that QE should have any effect and it might actually be detrimental to the efficiency of the financial system. Some economists have made the case that QE has negative effects, due to the fact that it withdraws safe collateral from financial markets, thus clogging up the “financial plumbing.”

This last view has some thinking that balance sheet withdrawal might prove to be stimulative in a way that QE “stimulus” wasn’t. If QE did hamper the collateral chains and flow of available securities for repo purposes, then less of it in SOMA might make for the opposite (loose) condition.

The problem with this way of thinking is that it is at best three dimensional (the starting point of reserves and mainstream economic treatment of money is two dimensional thinking). Repo is an important dynamic, but it is not exhaustive of the shadow world. There is much more than just collateral, as total balance sheet capacity is written, and erased, on things even economists like Williamson who are open enough to start looking will be shocked to find.

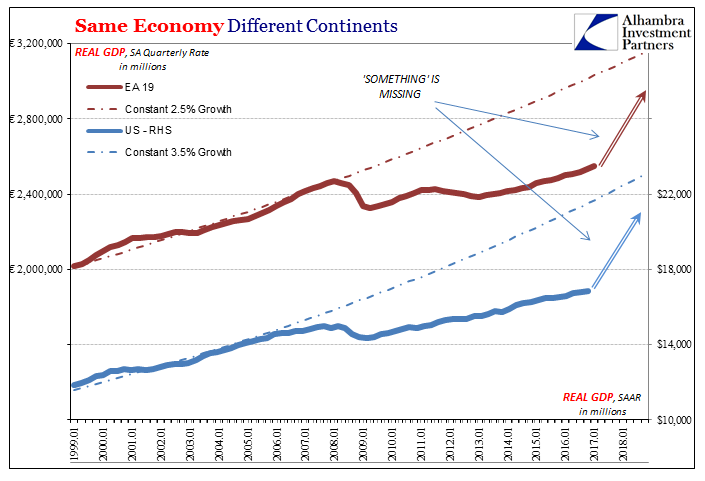

Offering evidence for QE’s futility, Williamson again does what we have done for many years. He actually looks at other places (like Japan) and finds that there is no correlation between balance sheet expansion and inflation or economic growth. Investigating the difference between the US economy’s performance and Canada’s, he finds that there actually hasn’t been much difference at all even though the Fed did a lot of QE and the Bank of Canada didn’t.

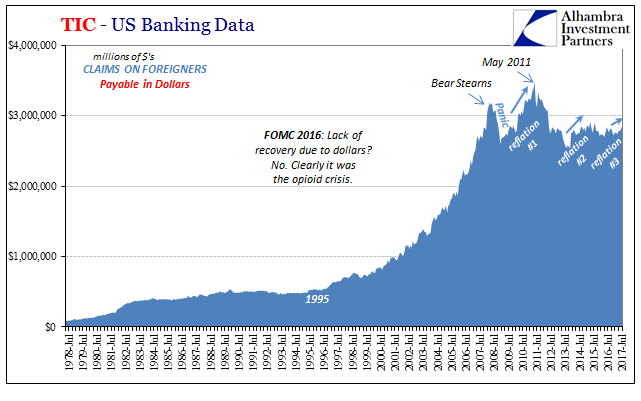

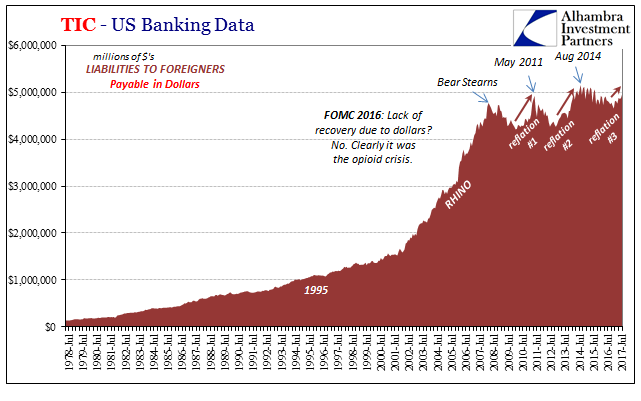

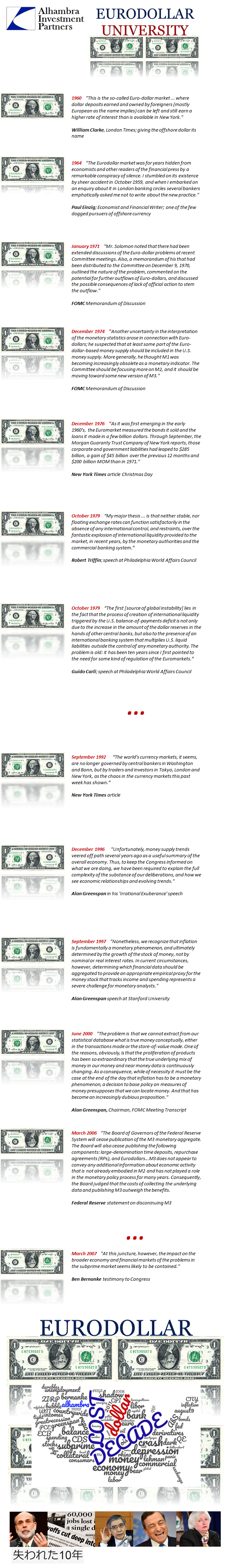

My overriding point is more than this; what I mean by that is the Fed’s irrelevance isn’t something that began with the QE’s and it’s far more than just Canada, the US, and Japan. It goes back much, much further than that, delves much, much deeper, and therefore suggests failure of more than just this one monetary policy.

In 2003, for example, none other than Milton Friedman made a similar discovery along these lines. Though his critique was contained within the debate of inflation and inflation targeting, in broad terms Friedman found what Williamson does now; that economic performance at various places around the world even then was largely the same even though central bank policies were often quite different.

I am a great admirer of Alan Greenspan and he deserves much credit for the improvement in performance, yet this simple explanation is not tenable. It is contradicted by the simultaneous improvement in the control of inflation by many central banks at about the same time, including the central banks of New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Canada, Sweden, Australia, and still others. Many of these central banks adopted a policy known as inflation targeting, under which they specified a narrow target range for inflation — 1% to 3%, for example. But inflation targeting and non-inflation targeting central banks did about equally well in controlling inflation, so explicit inflation targeting is not the answer.

It was as if some other perhaps outside monetary force was acting simultaneously on the world’s economies, making them into a single almost indivisible whole instead of separate systems patchworked together . That is, essentially, what Williamson’s study is also saying fourteen years later, even if he still hasn’t quite got all the way there yet.

The failure of QE and the uniformity of global inflation conditions many years ago are related through more than just how the repo market might explain a good part of the former. In truth, the real repo market as balance sheet capacity long ago departed specific borders. It wasn’t the dollar that replaced gold after Bretton Woods, it was the eurodollar or “dollar” that did even while Bretton Woods was still in force.

The consequences of a global monetary system fashioned in this way would quite logically be a more unified global economic performance, specified in all the ways economists and central bankers (redundant) don’t properly vet the modern monetary plumbing. The difference in that performance then versus now is that before August 2007 it worked, or seemed to, while after August 2007 it hasn’t and doesn’t appear, as Reflation #3 fades, to be moving even slightly in that direction.

Depending on economists even those more open-minded like Stephen Williamson to leave the comforts of their 1960’s worldview is a dangerous proposition. QE never should have been tried, for all that was necessary to see it would be a failure was right out in the open throughout 2007 and 2008 before the FOMC ever started discussing the program. It was, in the end, a tremendous waste of time, which is the real cost to the economy.

If it takes ten years to get into repo, how much longer before they get to the more complete stuff? Though this is a small step in the right direction, I don’t believe we have that much time given how much has already been squandered on bank reserves.

Stay In Touch