China is officially closed this week for its National Holiday Golden Week celebrations. These have been monetarily and financially eventful in the past because they represent challenges for RMB liquidity. This week appears to be no different, though this time it was the announcement of future policies that were no doubt written in the present tense of current monetary circumstances.

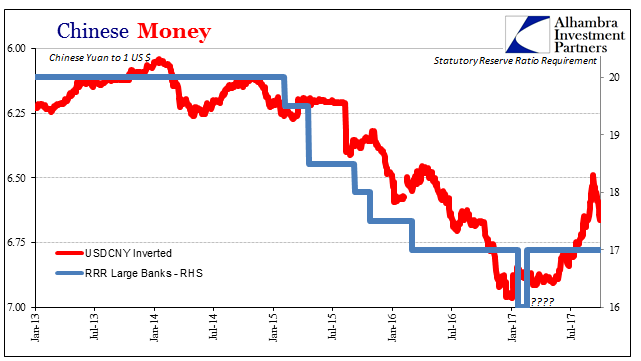

Starting in 2018, some Chinese banks will be eligible for a reduced RRR (reserve ratio requirement). The PBOC estimates that almost every bank of every size and business orientation will qualify for a 50 bps reduction, and that many might be able to achieve a 100 bps reduction for lending to small businesses or in the agricultural sector (if it sounds so very European in its targeting, it should).

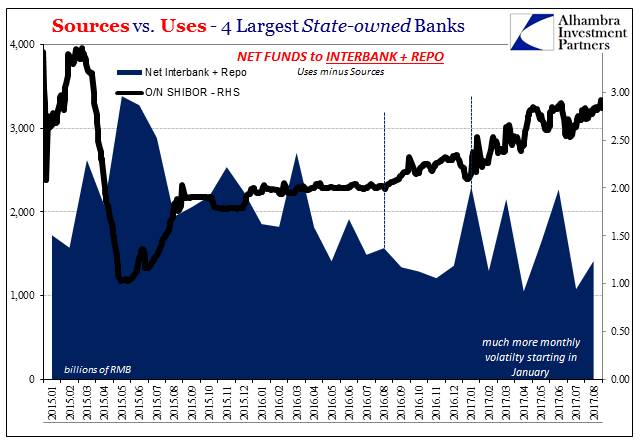

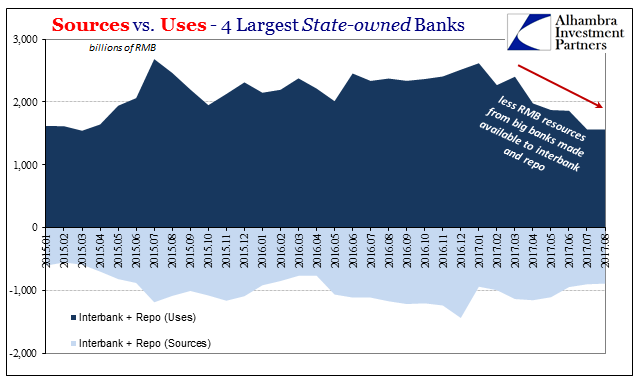

There are several implications from this policy, all of which are more evidence of the major policy themes we have been following this year. Tightening in China’s money markets seems to have become excessive such that the PBOC felt it warranted in at least this measured response. That can only raise questions about the nature of tightening in the first place (who, exactly, is tightening what?).

The second relates to the idea of de-dollarization and a stable CNY, while a third has to do with “dollar” implications and what the Chinese appear to believe about possible monetary conditions in the year ahead.

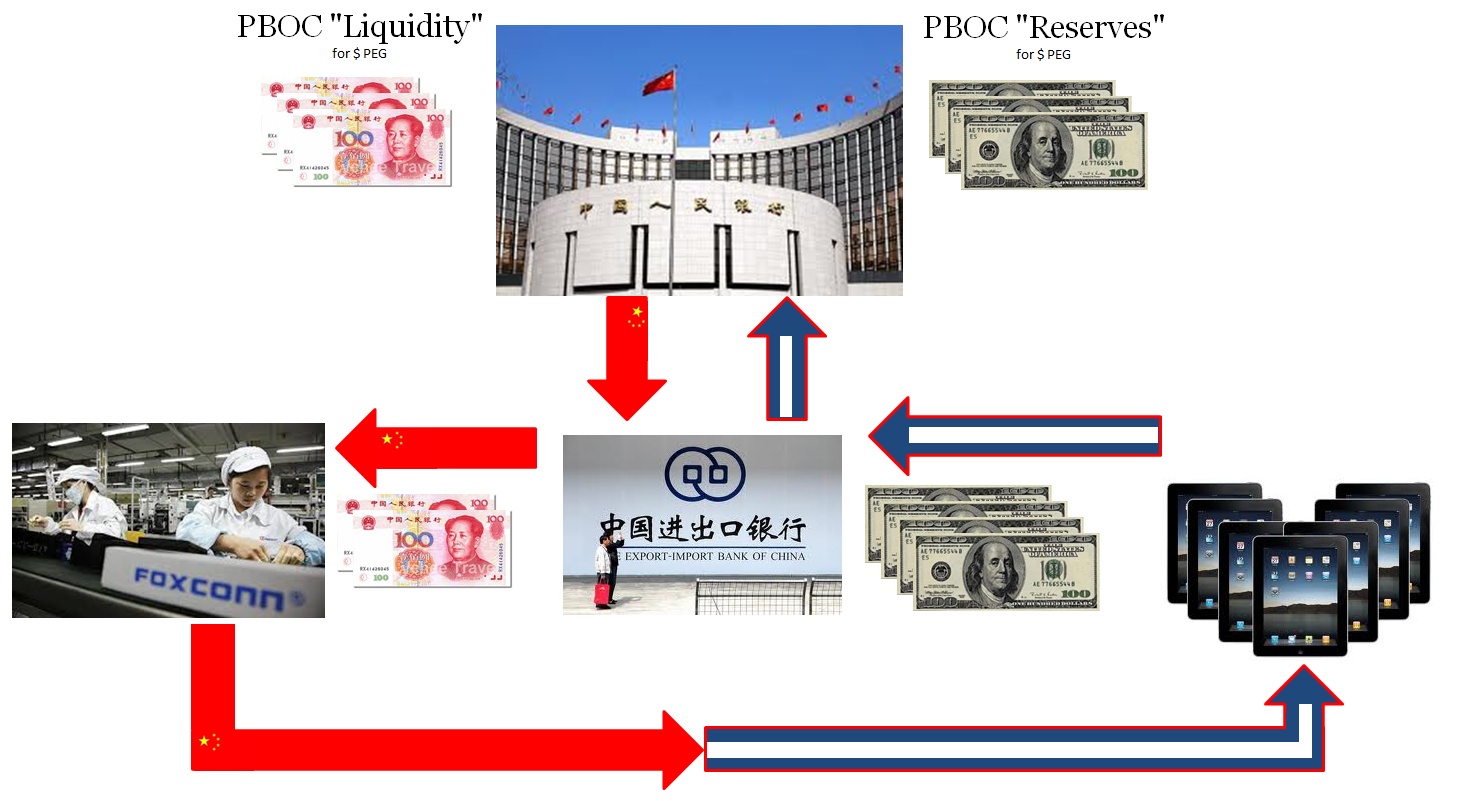

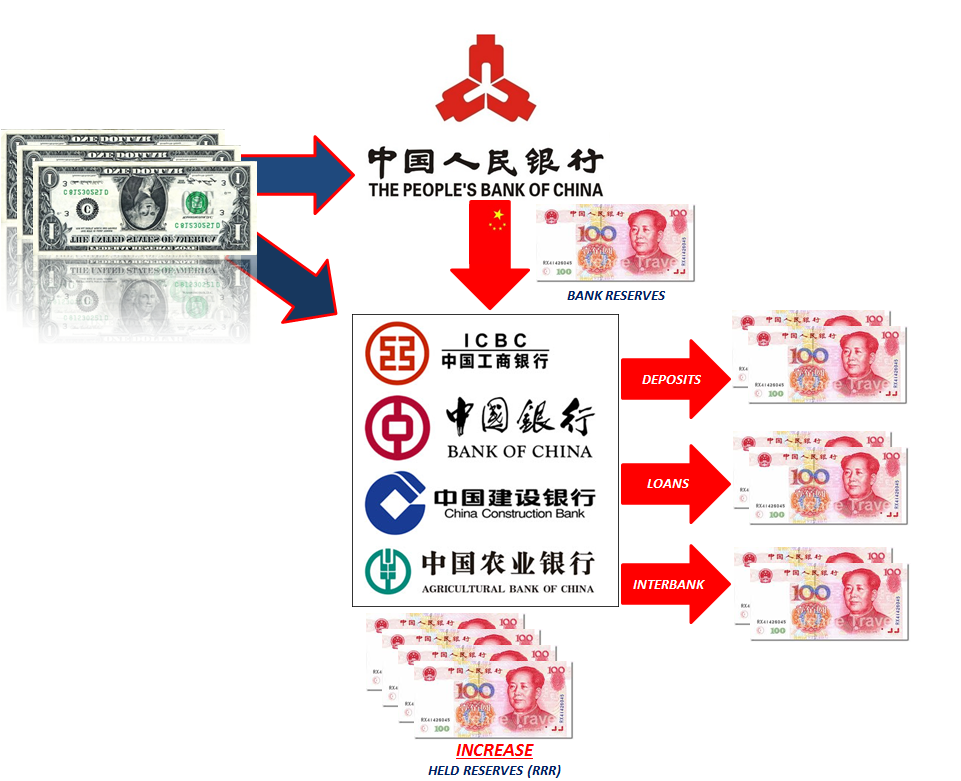

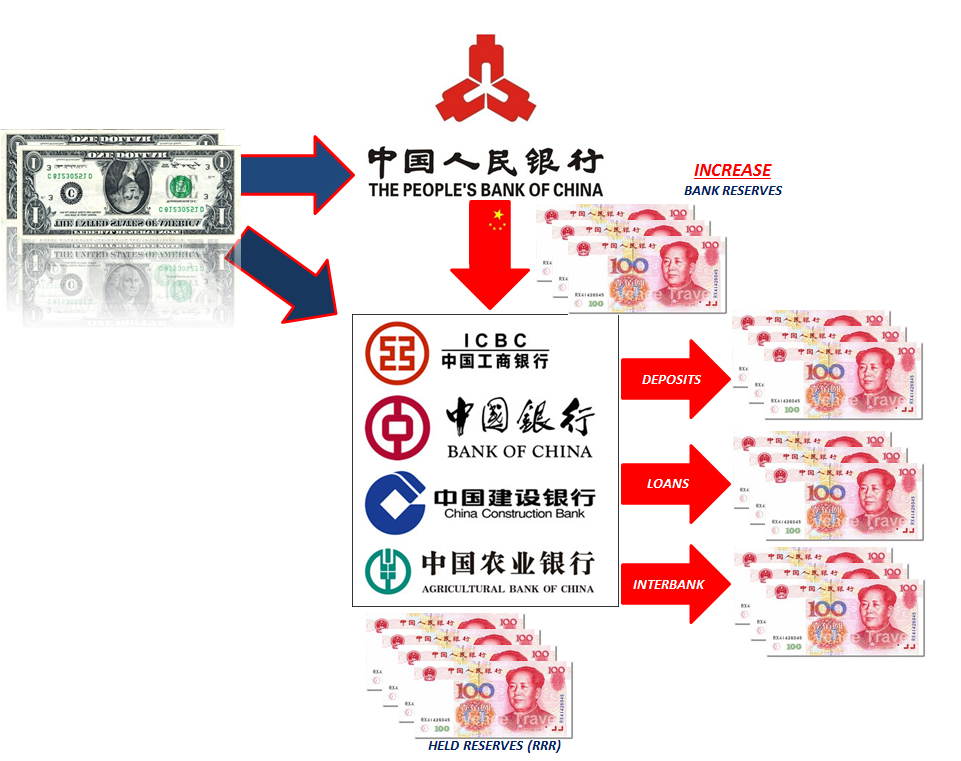

Those last two are both related in how the Chinese monetary system shifted through time since the major reforms of the early nineties. During the initial CNY peg period, the PBOC was at the center taking in dollars (and then more so “dollars”) as the basis for its RMB expansion. On a peg, internal liquidity control (RMB) was simple and straightforward (doesn’t mean it was always easy).

The most basic structure is what most people picture as the Asian version of the petrodollar, or a mercantilist system that recycles dollars for goods. This isn’t correct, however, or is at least crucially incomplete. The amount of dollars (really “dollars”) that were sent to China wasn’t really a function of the US trade deficit with that country. That mattered, but was amplified and augmented separately by investment flows (so-called hot money).

And that framework was further complicated by the global eurodollar system as the basis for all trade, inbound China imports as well as outbound China exports. The PBOC’s job was to regulate demand and supply of “dollars” as well as RMB for internal as well as external trade.

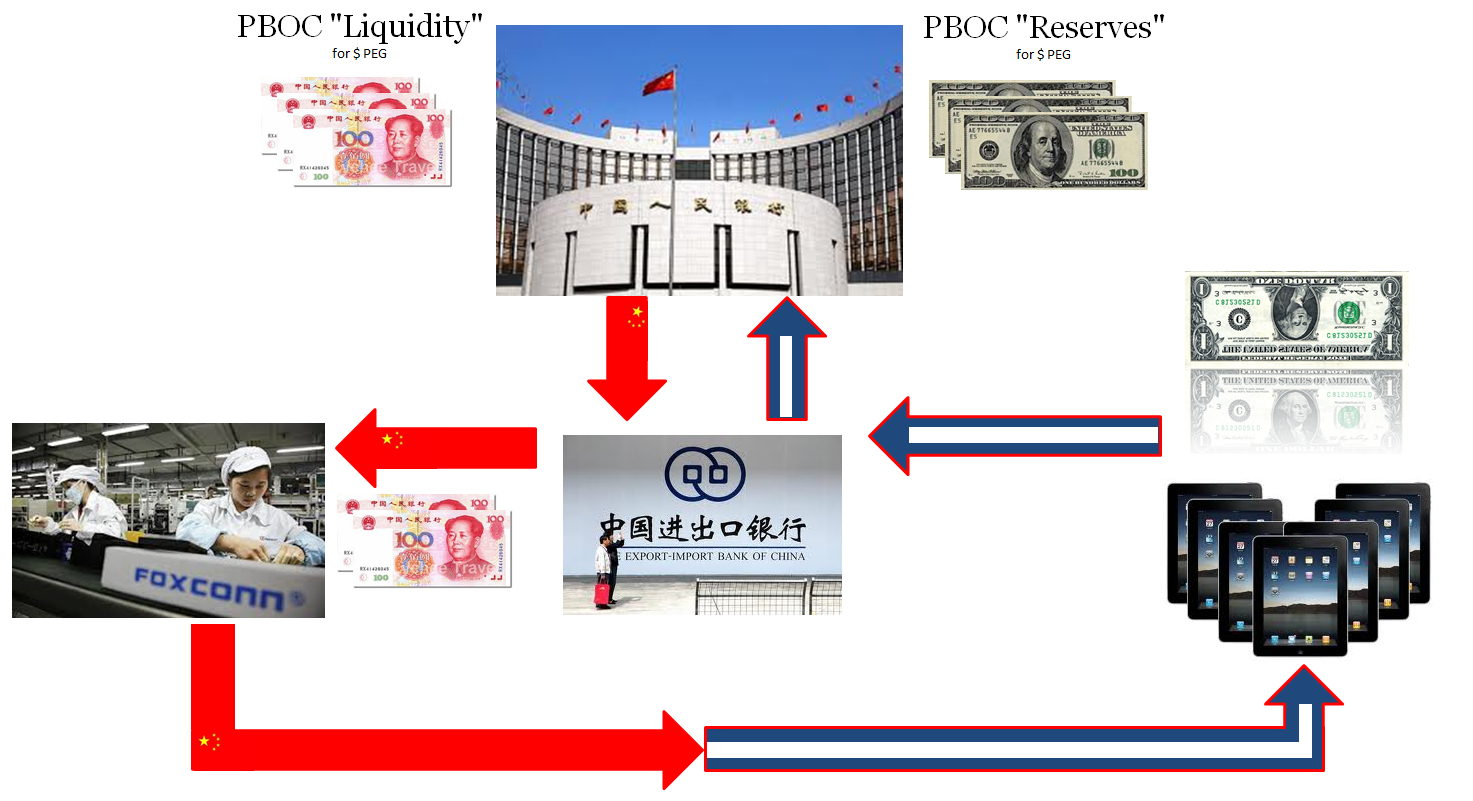

That job was complicated to some degree in July 2005 when Chinese officials allowed CNY to partially float. That meant some meaningful increase of inbound “dollars” available strictly to the private financial sector in China. In very simple terms, Chinese banks could then do what the PBOC had always done, create RMB from a “dollar” basis.

To regulate as much as possible this new more convoluted arrangement, the PBOC began to raise the amount of RMB reserves required for banks to hold as a liquidity buffer. Otherwise, as more “dollars” flowed directly to the private banks the greater the inflation risk (uncontrolled RMB expansion as a consequence of so many “dollars” coming onshore) in RMB.

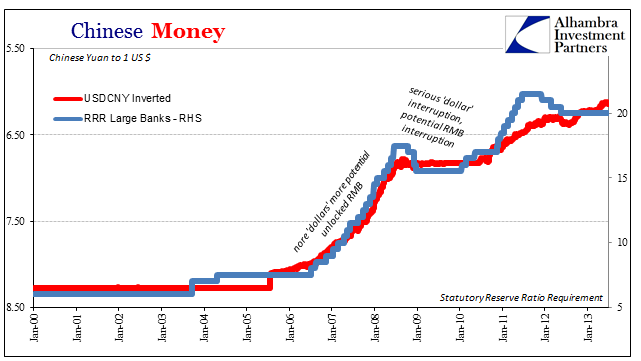

The more “dollars” that arrived on the balance sheets of Chinese banks, the more the PBOC raised the RRR especially for big banks. This is the basis for the very close correlation between CNY and the RRR.

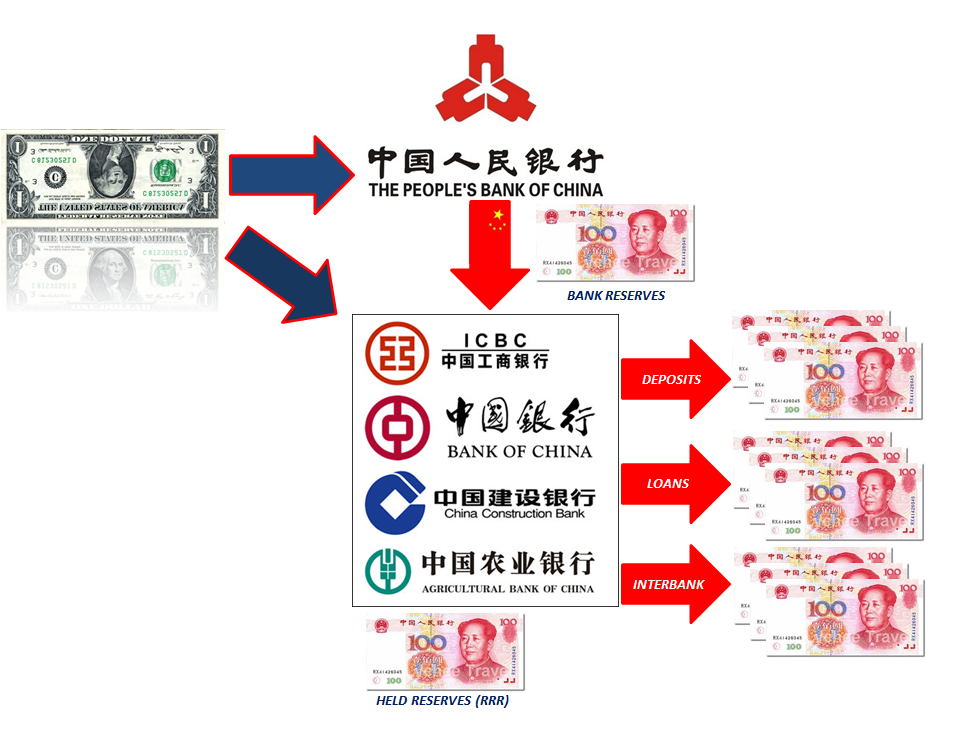

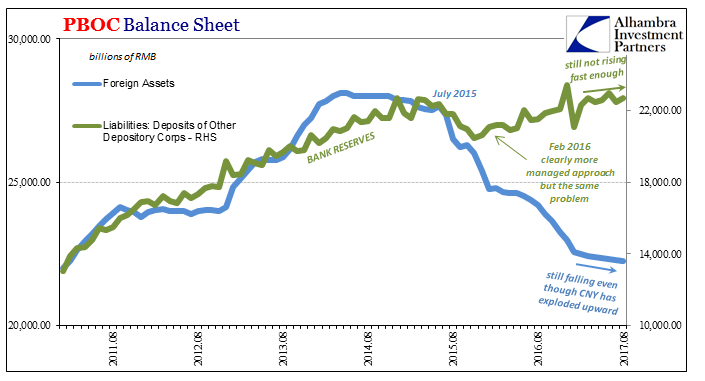

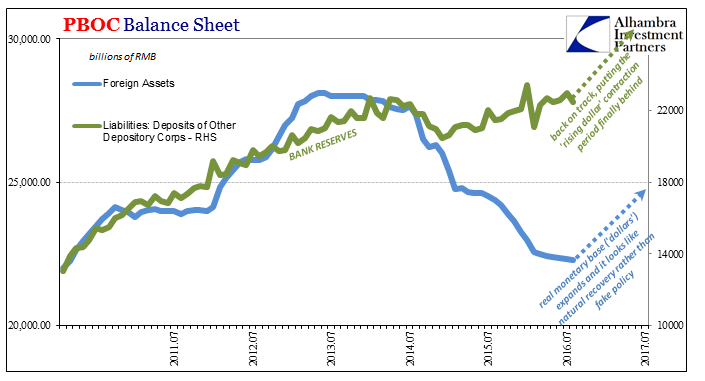

China’s major monetary problem since 2013 has been the opposite condition – fewer “dollars” both in the private sector as well as the central bank channel (limited float means the PBOC is managing and conducting some transactions, just not as many or in the same sizes as a peg). To counteract that reduction in base RMB money, the PBOC has several choices.

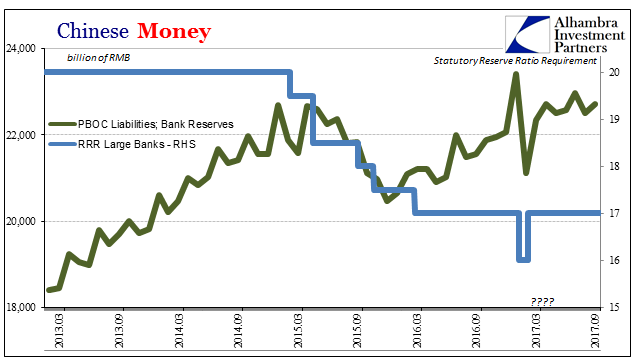

In late 2014, the central bank met the initial reduction in forex with a reduction in the RRR. It was textbook orthodox monetarism whereby the private banks were empowered to deal with fewer “dollars” by being able to still increase their RMB activities with less RMB held as statutory reserves.

It didn’t work; at all. This whole systemic arrangement was always unstable, but like everything else related to the eurodollar around the world it didn’t appear to be that way until it did. China spent the balance of 2015 with contracting “dollars” and nothing other than RRR cuts (as well as orthodox interest rate cuts) to counteract what was by then contracting bank reserves (due to the “dollars” flowing off the PBOC’s balance sheet).

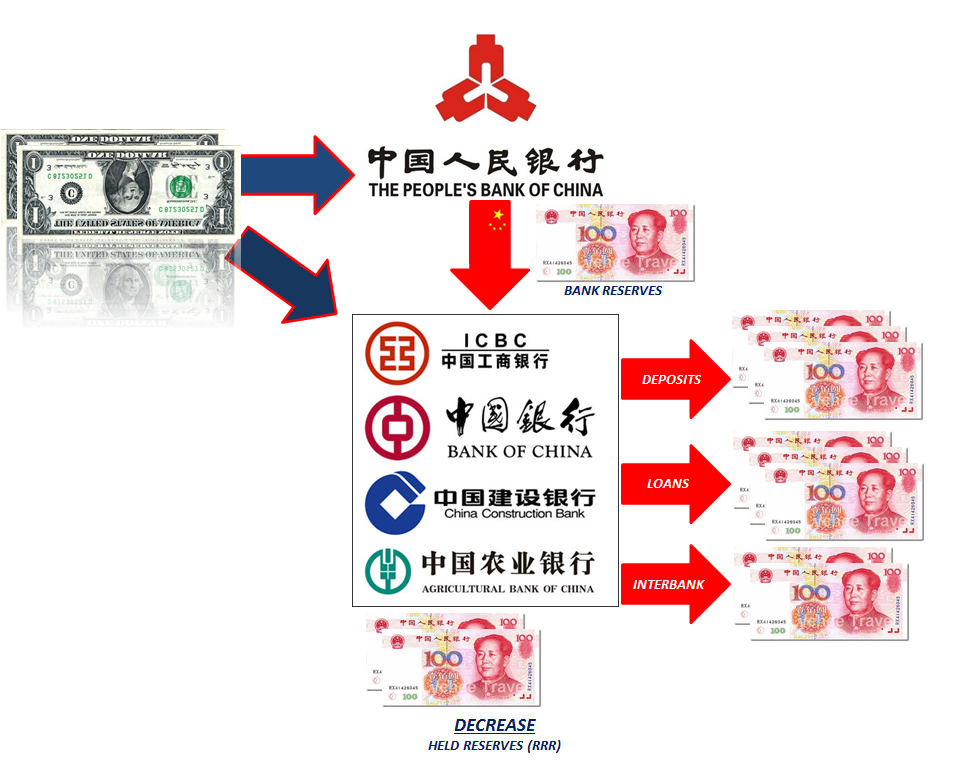

Beginning in 2016, the PBOC drastically changed its policies. It gave banks one more RRR for good measure in March 2016, but then abandoned that attempt in favor of direct strictly its own RMB policies. They in effect restarted growth in bank reserves (PBOC liability) channeled mostly through the biggest banks.

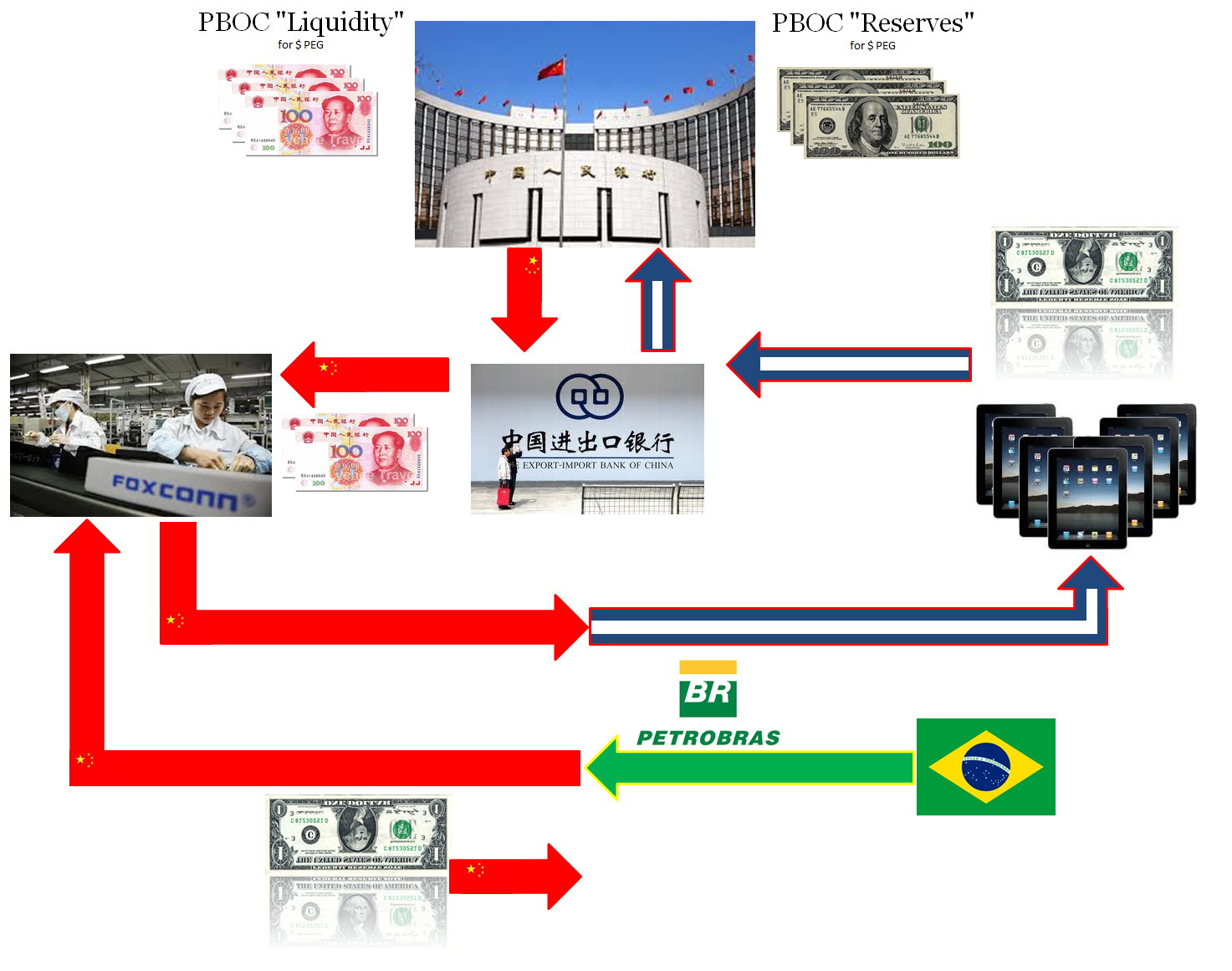

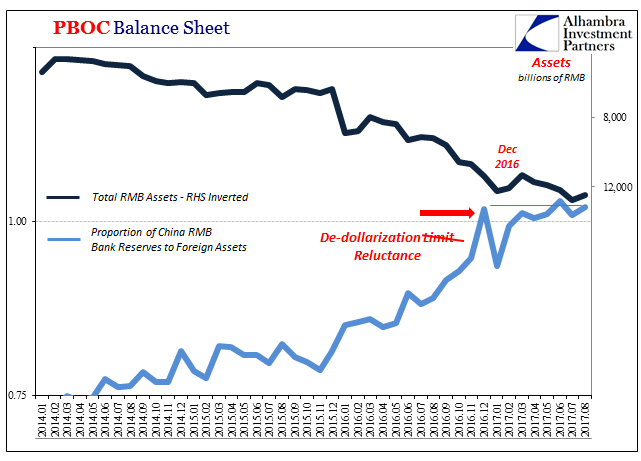

The problem with this approach is that it effectively de-dollarizes RMB. That doesn’t appear to be much of a problem on the surface, except that first (as shown in the Brazil example above) China will always need “dollars” so long as the global monetary system operates on a eurodollar standard. China may agitate and even be successful with small bilateral RMB arrangements for trade, but no matter how much it malfunctions the eurodollar system sadly remains the foundation of global commerce; and it really doesn’t appear as if that will change anytime soon.

Aside from still needing “dollars” to conduct trade, Chinese authorities finally figured out that decreasing the “dollar” backing of the RMB was probably not helping stabilize CNY and therefore China’s economy. While they had little choice in 2016, the upturn in the global economy has given them the window of opportunity to back off on RMB injections so as to avoid (for now) going too far down the de-dollarizing path. They have staked everything on CNY for economic stability.

Not only that, the RMB injections didn’t actually work. The media in the West talks about China as if it was 2005 again or nearly so, but the situation over there is nothing like that. In any meaningful sense, China’s economy didn’t really improve this year from last, it merely stopped getting worse. Thus, while it was of necessity to try some RMB printing in the form of bank reserves, there apparently were judged to be too many costs (unstable CNY) associated with it.

But without further RMB into the big banks, money and credit growth in China can only, and has only, tightened again. Thus, we are right back at 2014; and another round of RRR cuts to try to alleviate what is really a chronic external problem.

If the Chinese were truly intent on de-dollarization they wouldn’t be so reluctant about RMB “printing” in the form of PBOC assets creating bank reserves. The fact that they are going back to the private channel through RRR can only mean great reluctance to do so; especially in this context where RMB tightness is indicated practically everywhere in and around China (Hong Kong).

That doesn’t mean that China has abandoned all hope of global monetary reform, it instead recognizes that the country is right now in no shape to agitate for it and really no further along in that goal.

As for the eurodollar system, it appears as though Chinese officials at the very least don’t see much or any improvement in “dollar” availability. Since the RRR cuts are effective next year, we can reasonably infer that the PBOC and related government agencies are expecting little positive change on that account for the foreseeable future. The one thing that fixes all this is “dollar” flows; since that is practically impossible it appears as if China has finally reconciled its various positions to that probability.

Therefore, next year’s scheduled RRR cut is meant as an acknowledgement of ongoing deficiencies in global monetary reality without spooking CNY too much as the last remaining economic option.

Stay In Touch