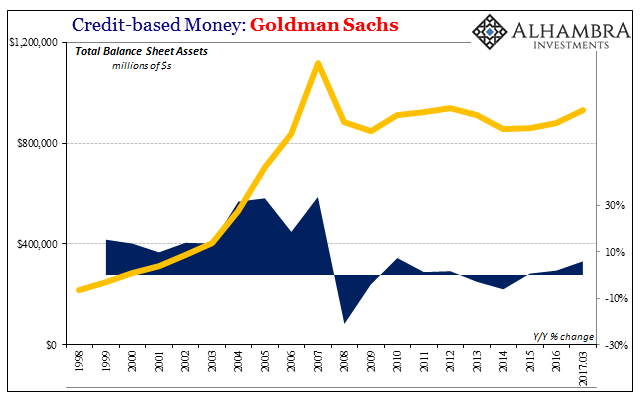

Goldman Sachs was the latest Wall Street bank to jump on low volatility. Despite an enormous gain in prop trading, most of the rest of the firm’s results were moving in the wrong direction. In its market making segment, for example, the firm booked $2.1 billion in net revenue in the third quarter, 22% less than what it took in during Q3 2016.

In FICC, the comparison was even worse:

Net revenues in Fixed Income, Currency and Commodities Client Execution were $1.45 billion for the third quarter of 2017, 26% lower than the third quarter of 2016, due to significantly lower net revenues in commodities, interest rate products and credit products and lower net revenues in currencies, partially offset by higher net revenues in mortgages. Although market-making conditions improved in most businesses compared with the second quarter of 2017, Fixed Income, Currency and Commodities Client Execution continued to operate in a challenging environment characterized by low levels of volatility and low client activity.

What goes on in these places is what is wrong for the whole global economy. As I wrote last week, it is a difficult link to establish in the official perception, let alone the wider common one:

The issue is, as Fitch highlights, the “bond-trading business.” The term itself only clouds the global economic issue further; workers all over the world are being screwed because banks like DB can’t make enough money in bonds? Forget that. It sounds so ridiculous that even sympathetic politicians aren’t going be able to make that connection.

There is very little actual bond trading in “bond trading.” The more basic discussion revolves instead around what is a modern bank, and how does that modern bank function in the monetary realm. We aren’t even starting at Square One with that conversation for several reasons, primary among them that what these banks, or really “banks”, do doesn’t fit into accounting statements or government statistics.

When the accounting was standardized, at that time a bank was largely a bank, immediately and easily recognizable as such by laypeople and officials alike; securities firms, separated by Glass Steagall, were a different matter but not so different so as to make accounting all that difficult or inappropriate. As money and global banking evolved, however, it became more and more challenging to describe these modern activities in the traditional format.

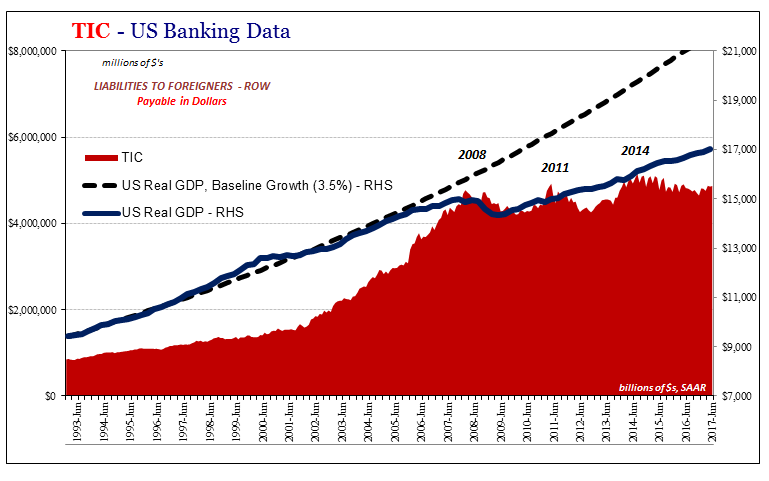

It’s been this way for a very long time, really diverging in the 1990’s – particularly after 1995 (RiskMetrics). I go back to LTCM for several reasons as a historical marker for the pace and really the scale of this evolutionary adoption, among those the systemic departure from simple accounting.

From the September 1998 FOMC discussion about the systemic issues LTCM’s “unexpectedly” far-reaching tentacles had created:

CHAIRMAN GREENSPAN. Somebody mentioned to me that Bankers Trust had an August balance sheet for LTCM. Is that true?

VICE CHAIRMAN MCDONOUGH. Yes, but the balance sheet is a relatively small piece of the whole action because so much of the latter is off-balance-sheet.

LTCM wasn’t an outlier; it was merely the first that got caught out in the open in grave trouble (pioneering the pathology of failure Bear, AIG, and Lehman would later “perfect”). The only way in which it touched the accounting statements was often through income, including FICC or “bond trading” that didn’t really fit the description any longer.

One long-time veteran insider wrote me today (and I thank him very kindly for this contribution) his personal story of the often counterintuitive (as he put it) perspective in accepting what banks used to do as opposed to what “banks” actually do:

November, 1998, I started with UBS as deputy head of trading for the private bank in NYC. I had come from the sell side as an equity trader and thus was inexperienced with buy side fixed income trading. My colleague – JR – was introducing me to this new world:

JR: you’re gonna do the REPO.

ME: REPO?

JR: yeah, we have a good client who runs money for a big family office. He arranged with the IB (UBS Investment Bank) to do REPO.

ME: Repurchase Agreement.

JR: yeah, he places 5 mil cash with us and the IB pledges collateral to him overnight.

ME: how much do we make?

JR: the private bank takes 5 bps off the rate.

ME: doesn’t sound like a lot, why bother?

JR: it’s enough. He does it every night.

ME: every night?

JR: yeah…your job is to call the IB…get the rate…and pass the ticket.

ME: every night?

JR: you’re new, this will give you a good start on the fixed income stuff we do….

Yeah, bond “trading”….

The profit parts of the eurodollar equation run largely through FICC and a few other places (depending upon the specific firm’s policies). That gives us a sense of at least the return piece of risk/return. The footnotes give us another sense of the risk part, though that is often far more difficult to put together in the shorter terms.

In the end, however, more than enough time has passed to reasonably determine that risk/return in “bond trading” has been totally and irreparably upended; the banks themselves are telling us that by what they do, not what they say. They refuse to grow because the risk, primarily liquidity risk, is too much for what little return might be available (meaning modeled).

It sets up an almost unbreakable positive feedback loop that four QE’s in the US could barely touch; the more banks feel too much risk for too little return, the less the economy recovers, furthering the negative perceptions about opportunity and risk. Why not just buy and hold a UST, or negative yielding German bund, to better insulate the balance sheet against liquidity or whatever other relatable risk? If that helps meet the new LCR, so much the better for a range of only bad options.

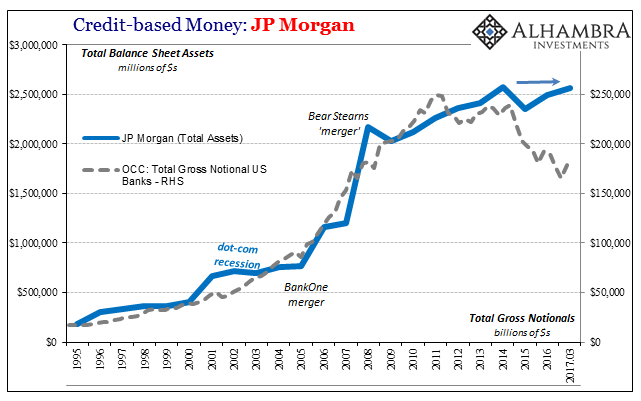

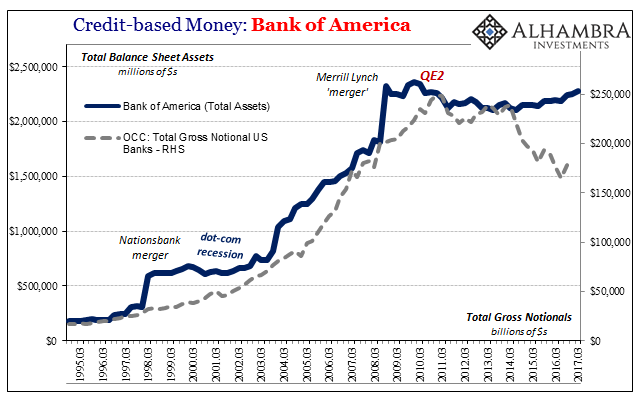

It spreads like contagion through the aggregate derivatives book on the one side (dark leverage), and systemic liquidity capacity (like repo) on the other. If Goldman Sachs, JPM, and/or Bank of America behave like this, they offer less risk absorption capacity to the rest of the system, thereby leaving that rest with fewer options for managing their own activities. Uncertainty, even defined as the lack of fluid, cheap derivatives, is greater risk. The result, as we see all over the world, is that banks are shrinking in non-linear fashion as well as outright (such as Goldman Sachs), weighing down monetarily the whole global economy.

We need first to define modern banking so that we can then define modern money. Only at that point can we tease out and capture the global system from where it starts now deep in the footnotes. Only then will the broader global population be able to make the economic to monetary connection that is almost impossible to see right now. “Bond trading” is too broad of a term to be useful, but it fits perfectly highlighting this misalignment of how things actually work and how those things are improperly accounted for by anachronistic rules and terms.

Stay In Touch