Hong Kong carefully built its sterling reputation (pun intended) over many years and decades. Through mostly careful rule and careful adherence to rules, there was no imbalance too big or too tough that the HKMA could not readily handle or absorb. The result was a condition that every central bank and monetary authority should strive for.

As I wrote back in July:

Its solution was simple and orthodox; peg the Hong Kong dollar to the US dollar. Over the years, the HKMA was tested a few times, especially during the Asian flu of 1997 and 1998. Unlike its Asian neighbors, Hong Kong never came close to devaluation and economic destruction, even as China took over sovereignty amidst its own Asian flu symptoms.

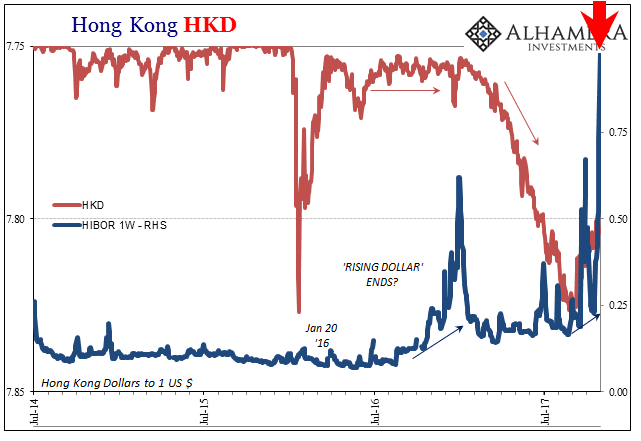

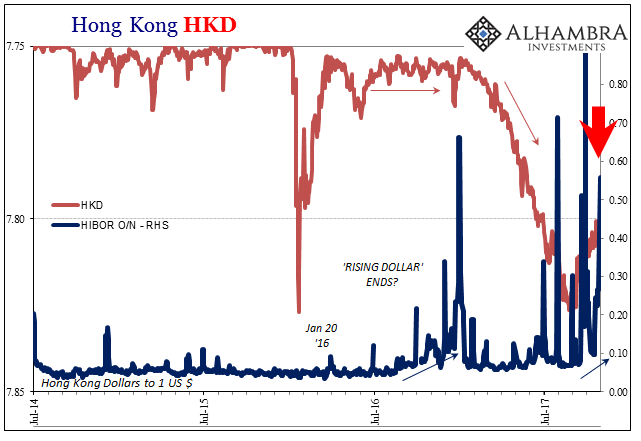

It earned the HKMA and its HKD currency a quality that is so often unappreciated in modern times: boring. The peg had been successfully instituted and defended to get the exchange value to around 7.8 HKD to 1 US$. From there, it floats in a limited range now settled between 7.75 and 7.85.

It appears more and more possible that there was, in fact, one factor even the mighty HKMA could not overcome: China. It’s a bit odd to make that claim now, with HKD trading above 7.80 for the first time in months. The Hong Kong dollar has been moving in the right direction for seven weeks, so things are surely getting better (subscription required)?

So now you’ve borrowed a bunch of “dollars” on behalf of Chinese banks and the mainland central bank, committing yourself to continual rollover risk since it isn’t likely you will be able to say no once you’ve said yes to the PBOC. Then the cost of obtaining these “dollars” for Hong Kong banks suddenly rises, meaning the premium paid for them (in FX) spikes in the form of HKD “devaluation.” At some point, no matter how beholden to the PBOC, you have to cry foul and try to make it stop.

Let’s assume that the mainland central bank hears your pleas as well as surely those of others in the same situation and grants your reprieve. They let China’s onshore banks back to fend for themselves, closing down or decompressing the ad hoc Hong Kong eurodollar pipeline. HKD starts to rise again, CNY to fall. That’s it, right?

Well, no.

That’s the thing about unwinding things. You get them going using leverage, often boatloads of it because of what economists call hysteresis – the big upfront expenditure it takes to get something moving, like trying to launch a rocket from a standstill on the ground. It sometimes feels as if there is symmetry to these things, that once it stops going one way it will go the other way smoothly, easily, and in the same proportions.

The vast majority of the time it just doesn’t work like that, but especially when the hoped for result that iniated of all this intervention doesn’t materialize.

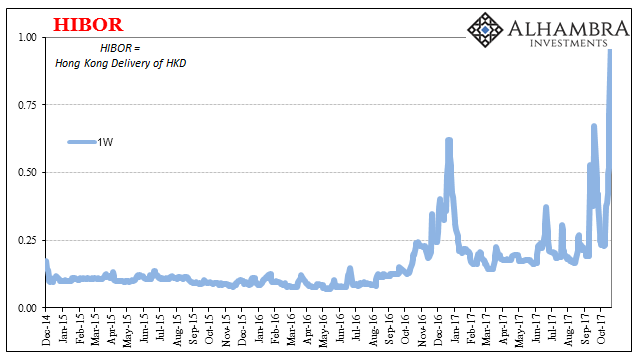

HIBOR rates have made Hong Kong the Asian epicenter of exciting, and that’s a very bad place to be if you are Hong Kong. The overnight rate has spiked to nearly 60 bps again, the equivalent of 3-month HIBOR (CNH) at 8% or 10%. The one-week HKD HIBOR rate was just shy of 1% today, 99.107 bps. That’s off the charts (literally, below).

Even though we aren’t sure what’s going on exactly (I have thrown around some ideas), there are two bits of important information from which we can derive an outline of conditions. The first is HKD driving higher, meaning an unwind of the prior year’s buildup of that ad hoc eurodollar pipeline.

The second is HIBOR which though it doesn’t immediately seem to connect to “dollars” and CNY suggests that unwind is going very poorly. The overriding issue with all credit-based currency systems, even traditional monetary systems tangentially connected to credit-based formats, is balance sheet capacity. If it becomes impaired through one means, or in one currency (say, eurodollar rollover risk), it becomes impaired in all currencies (say, Hong Kong dollars).

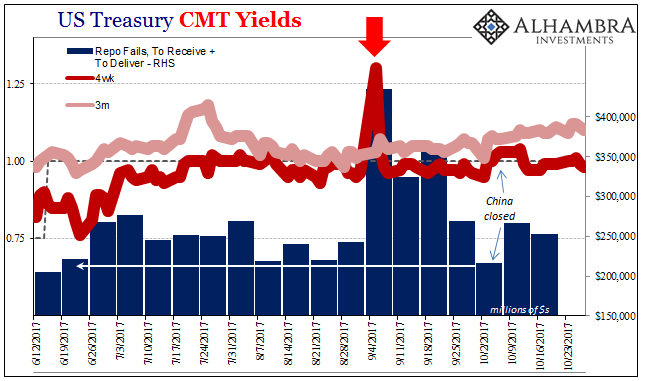

What I would like more clarification on is what it was, specifically, that forced the unwinding to start. It’s possible this was an intentional redirection as a matter of calm, rational policy (the way everyone in the West looks upon Chinese matters particularly where the supposedly omniscient PBOC is involved), but I highly doubt it. There was created, as always, some funding imbalance that at least involved global US$ repo collateral.

If there is one universal law in trading, finance, and money (or FICC), it’s always easier to get in than to get out. From China’s perspective, it made sense to try to use Hong Kong’s reputation for their “dollar” problem. However, like everything else so far, they may come to regret doing so, as banks in Hong Kong may already be cursing the effort.

Stay In Touch