There is no argument that the New Deal of the 1930’s completely changed the political situation in America, including the fundamental relationship of the government to its people. The way it came about was entirely familiar, a sense from among a large (enough) portion of the general population that the paradigm of the time no longer worked. It was only for whichever political party that spoke honestly to that predicament to obtain long-term political success.

It was perhaps easier to do so then, not least because the Great Depression was immediate and far too tangible. Whatever you might want to call whatever economic condition we have been in for the last decade, depression works for me as a more-than-temporary destructive economic deviation, it is of an almost hidden or obscured variety.

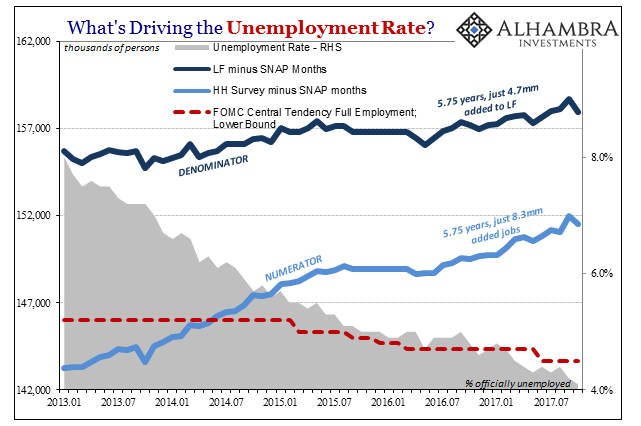

One big reason for that is Economists. Politicians don’t want to challenge them not because they have great expertise about an economy, any economy, but because they speak in a foreign language that to an outsider sounds scienc-ey. The political class fears challenging the unemployment rate, which Economists have held sacred, for how they might be embarrassed on what are really unrelated topics. The issue for Economists is a particular differential equation when for the rest of the world it is work, the tremendous lack of.

I really don’t understand why every D campaign message isn’t: More Jobs, Higher Wages and a Government that works for you. https://t.co/GBK3mMBFhj

— Chris Hayes (@chrislhayes) November 4, 2017

More and more, though, even the formerly recalcitrant unemployment rate adherents are starting to get it, and see it. It’s more than a little ironic that as the unemployment rate goes lower the easier it is to grasp. At now 4.1%, thanks to even more Americans falling out from its denominator, there is little left to argue about.

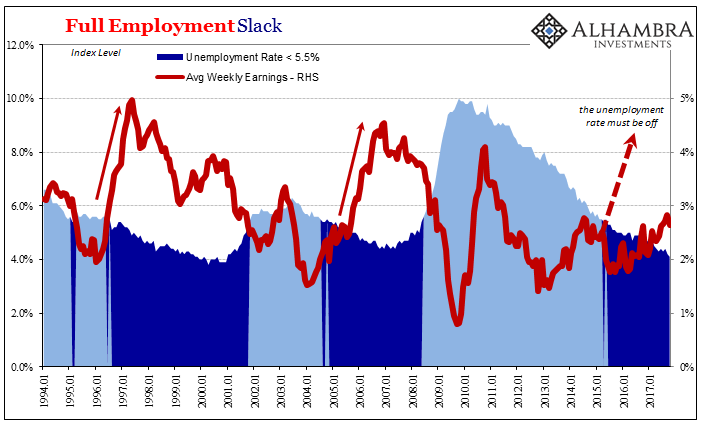

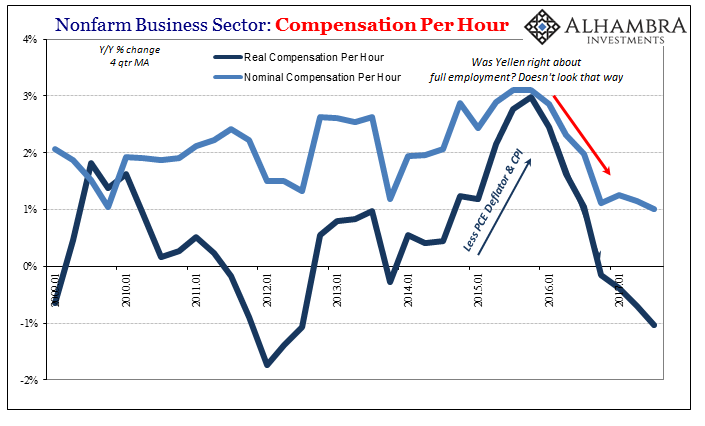

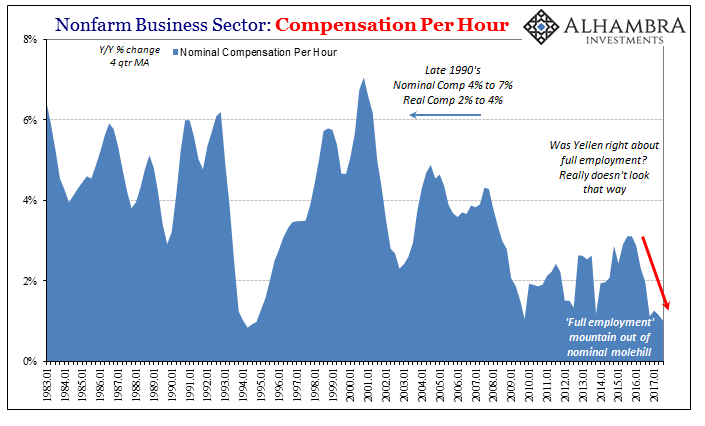

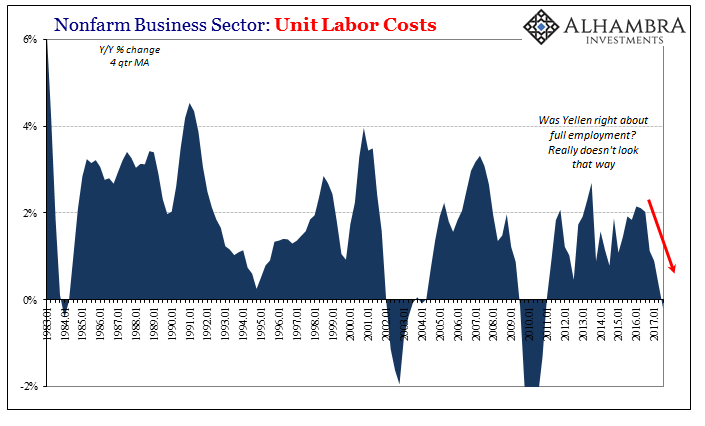

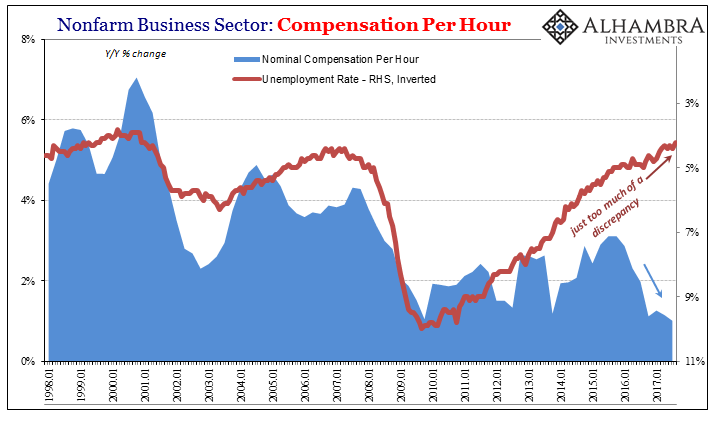

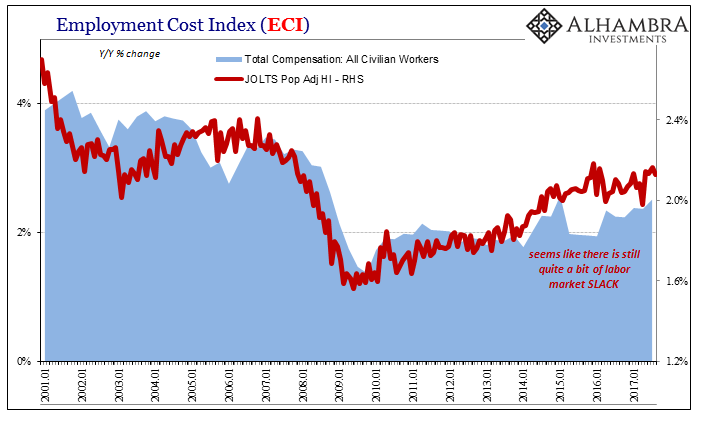

The evidence is really overwhelming. The BLS tracks separate data series (productivity) on wages and labor income apart from its monthly CES. From nominal Compensation per Hour to the Employment Cost Index to Unit Labor Costs, all of them are uniformly, authoritatively challenging the view of the labor market and economy presented by the unemployment rate.

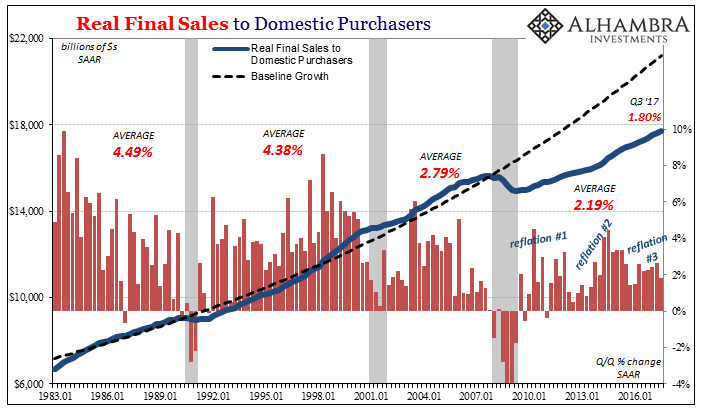

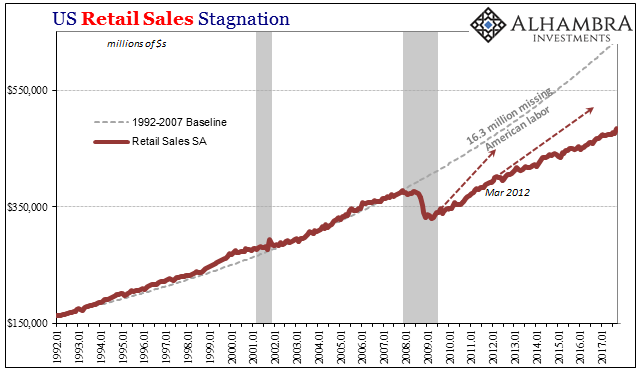

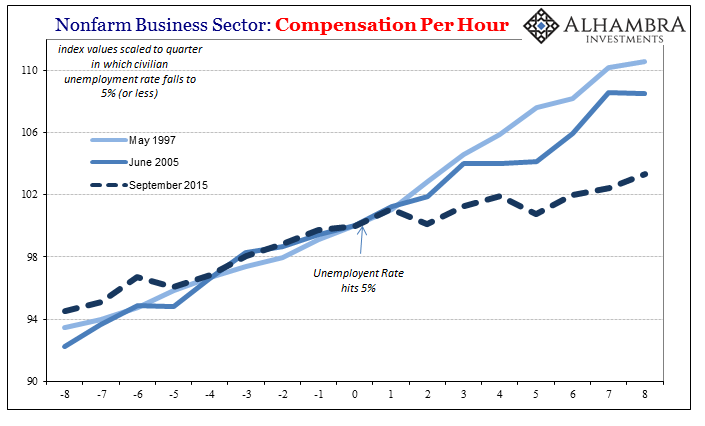

If labor market slack was truly all used up, as a 4.1% unemployment rate demands, then nominal compensation wouldn’t just be rising slowly here and there, it would be surging in a manner consistent with past periods of the same condition. The last few times the unemployment rate fell to around 5%, that is exactly what happened. This time, however, it isn’t even close.

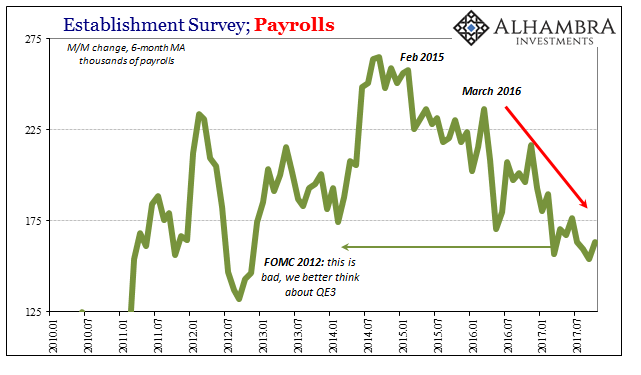

In fact, as you can plainly see on all the charts above, labor compensation has actually slowed over the past few years as the unemployment rate fell first under 5% and now significantly below that level. That’s because the labor market in reality slowed down as an effect of the “rising dollar” and the near-recession it produced; a downturn Economists were absolutely sure wasn’t going to happen and still have yet to acknowledge several years after the fact. It has left the unemployment rate off in a world of its own, totally uncorrelated with anything else of meaning.

There isn’t the slightest detectible hint of wage pressures, and therefore inflation pressures, as the FOMC in particular has been desperate to find. All indications instead point to continuing heavy slack in the US labor market even after ten years of Economists claiming some level of recovery (their definition of that term diminishing over time).

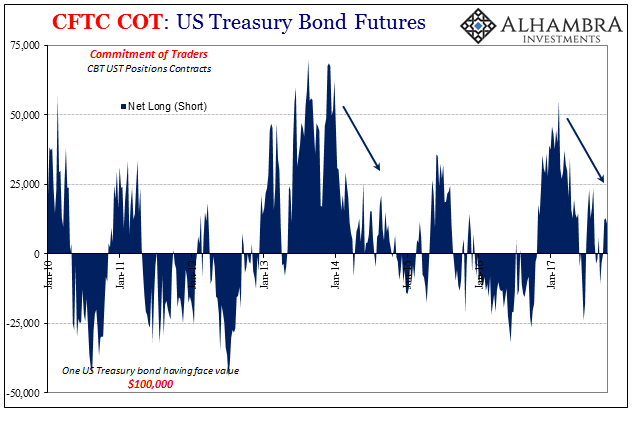

Without wage pressures, there is no basis whatsoever to expect inflation will suddenly surge or even start to behave (the PCE Deflator has been less than the Fed’s self-mandated 2% for more than five years), and without those wage and inflation pressures the idea of interest rates have nowhere to go but up simply vanishes into the same dreamworld where each of the past recovery narratives already reached their humiliating end.

The policymakers at the Fed just aren’t data dependent and they have never been. Economists set their expectations based on the Fed. We could detour this discussion into the evolving state of “forward guidance” to see that in policy terms, but at this point it would be unnecessarily byzantine and redundant. The unemployment rate, again, is doing that for us. There is at FOUR POINT ONE no need to be complicated over what is really simple and easy.

In political terms, it is just that simple and easy. Whichever party, in whichever country, stops listening to Economists and starts taking workers’ grave concerns for the serious matters they are will be positioned for electoral success now and well into the future. The New Deal, right or wrong, made it seem as if Democrats cared about workers, a feeling and an evolved voting pattern that lasted for generations. It didn’t even matter that, and this is the part subject to argument, it didn’t do much for them in the end (and in my view made the Great Depression longer and worse, stifling the recovery and contributing to the fatal blow in 1937).

In other words, in an ideal world it would be nice where the politics unlike in the thirties would align with the economics (small “e”) such that one party or the other would finally take the side of workers over Economists and do so in a way that actually leads to recovery and growth (rather than global destruction and war). That may be, however, too much to expect, for as difficult as it has been for the mainstream to look past the Economists’ projection of the unemployment rate into the real labor market it would be an order of magnitude harder for it to do so in the correct “dollar” terms.

Stay In Touch