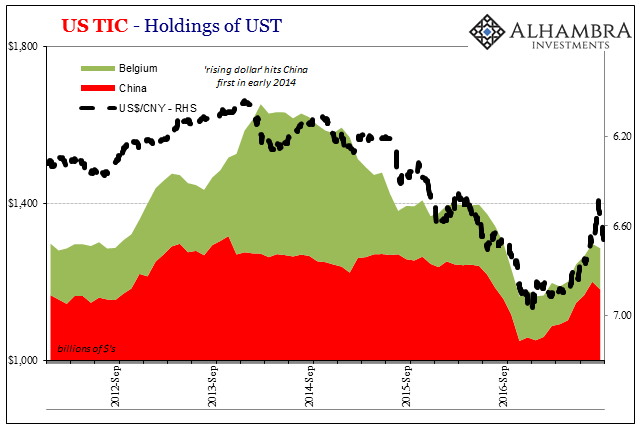

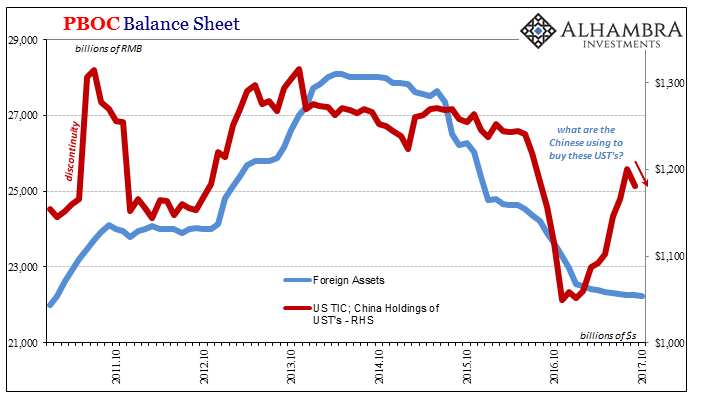

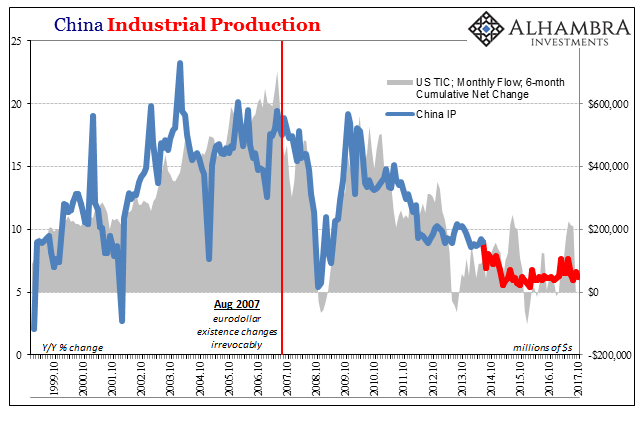

The latest update of the Treasury Department’s Treasury International Capital (TIC) estimates clarified a few things. To begin with, for the month of September the Chinese sold UST’s again for the first time in seven months. Between the end of January and the end of August, the Chinese had added $149.4 billion in UST holdings. In September, however, the balance was reduced by $19.7 billion.

The change back to selling them wasn’t a surprise. CNY stopped rising early on in September, clearly reversing as did the Hong Kong dollar at the same time. We can add Belgium’s holdings to China’s and the net was still a negative coincident to the shifts in currency exchange.

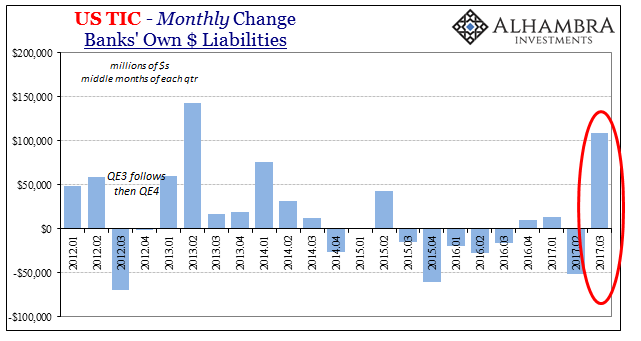

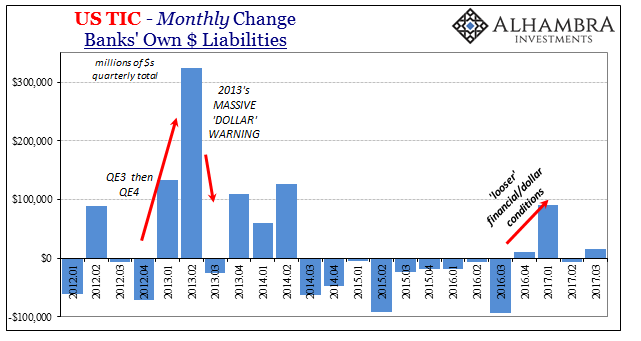

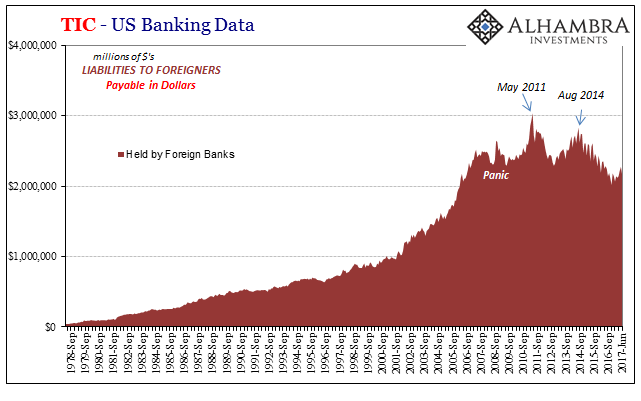

The other matter for TIC to clear up is the ongoing breakdown or change in the quarterly pattern of dollar bank liabilities to and from overseas. For the month of August, the Treasury Department figured an unusually large increase in them far out of line with middle month behavior in recent years.

There really wasn’t anything else suggesting rapid growth in the cross-border dollar business, so it seemed either an outlier or part of the shifting pattern of intra-quarter activities within the eurodollar banking sector. The update for September shows that it was indeed the latter.

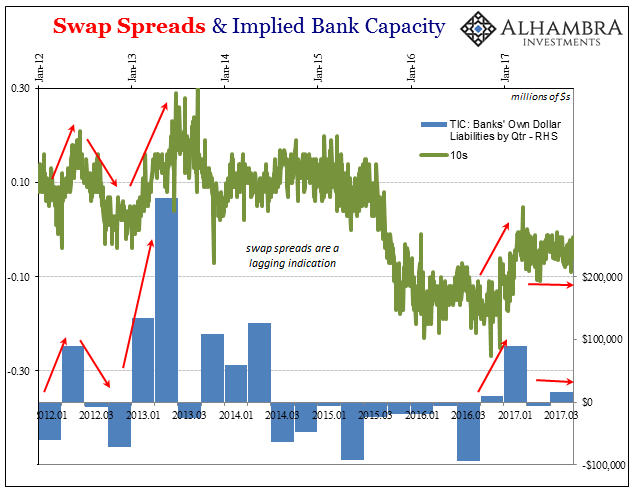

Bank liabilities declined by a net $118 billion in September, offsetting August’s jump, leaving the quarterly total nearly flat. That’s much more consistent with global dollar banking since the “rising dollar” began. And it’s also corroborated by market prices such as swap spreads.

It isn’t at all clear why the quarterly pattern has shifted for banks, nor is it clear that it is actually banks doing something different. It may be a difference in crunching the statistics or even in data collection.

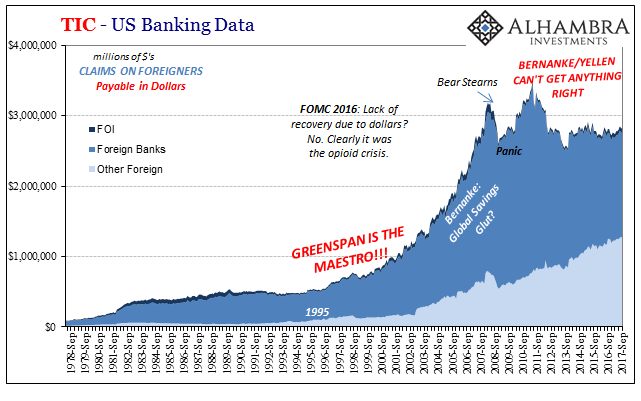

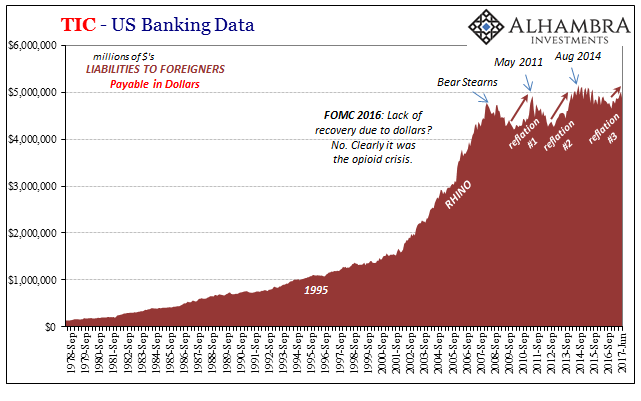

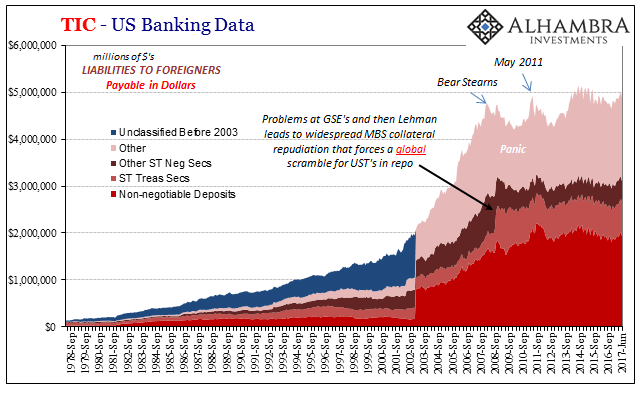

Whatever the case, the eurodollar decay rolls on and it does so exclusively and explicitly within the bank channel. As a proxy for bank balance sheet capacity, and therefore what counts as global “dollar” supply under a credit-based currency regime, the TIC banking data may be as good as it gets.

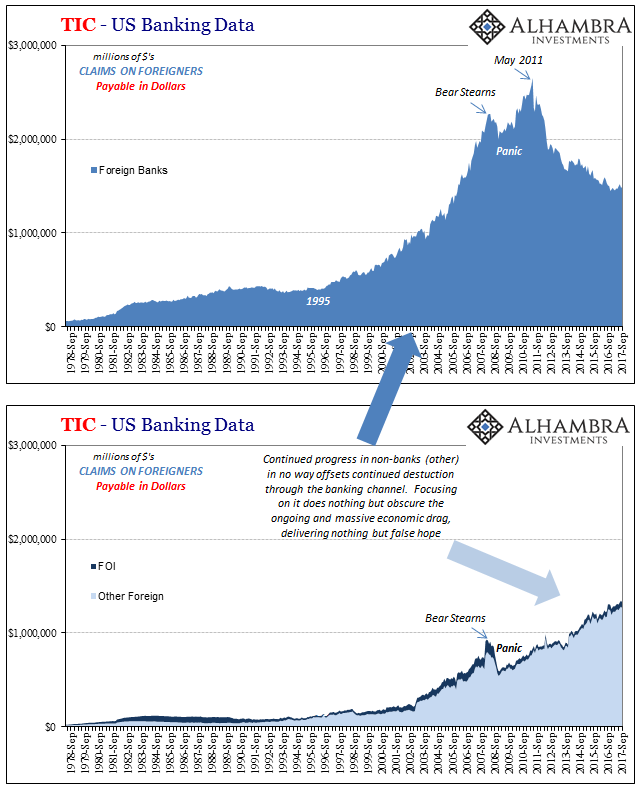

When you separate the whole into its parts, balances are still gaining through non-banks while contracting in the much larger banking section. It’s this way both in both inbound as well as outbound dollar flow. This is not a distinction without a difference, as there is more to the global funding issue than changing balances one to the other.

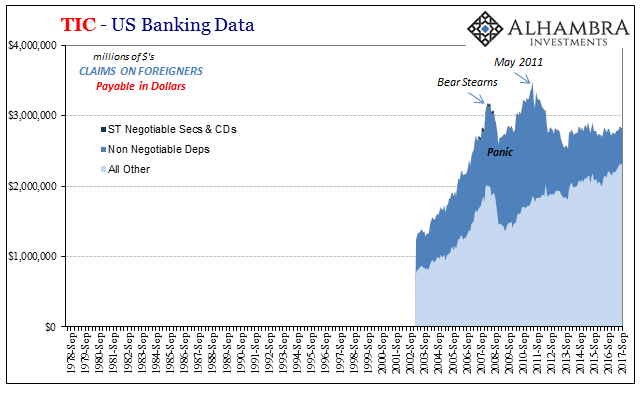

The disrepair in the banking channel has greatly affected exactly what it is that is coming in as well as going out. On the latter side, US banks sending “dollars” out to the rest of the world, we don’t exactly know what form most of those take; or at least the TIC data doesn’t discriminate to that level of detail. Almost all of it falls under the category “Other.”

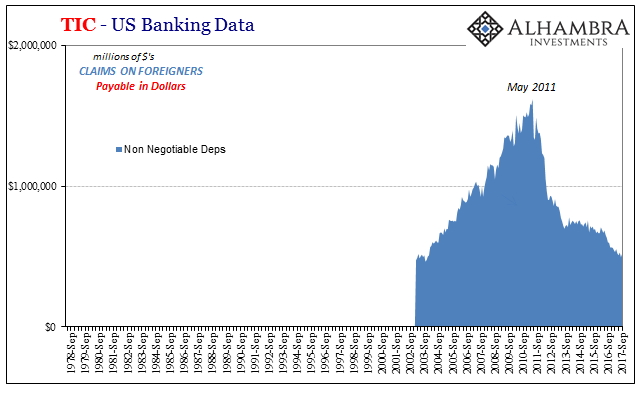

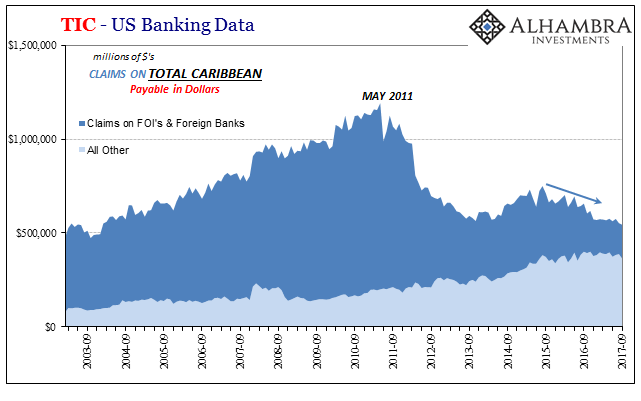

That’s more and more all that’s left in this segment, as Non-Negotiable deposits have practically disappeared since May 2011. This is, or was, the original basis for the eurodollar system and it was the quite traditional connection between US banks and the first global redistribution point – offshore banks in the Cayman Islands and scattered around the rest of the Caribbean.

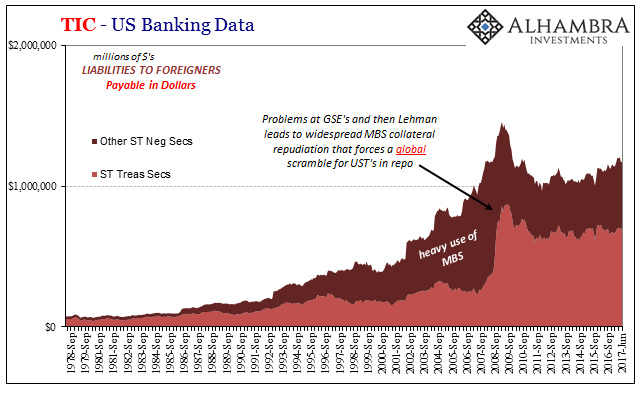

There is more detail as to what’s coming back to the United States from overseas banks. Though about half is still categorized as “other”, the bulk of the rest is Non-Negotiable deposits (eurodollar deposits). Of what’s left, it’s largely the recycle or renting of overseas US$ assets especially UST’s. In other words, this is the repo channel for collateralized flow from outside the US back in.

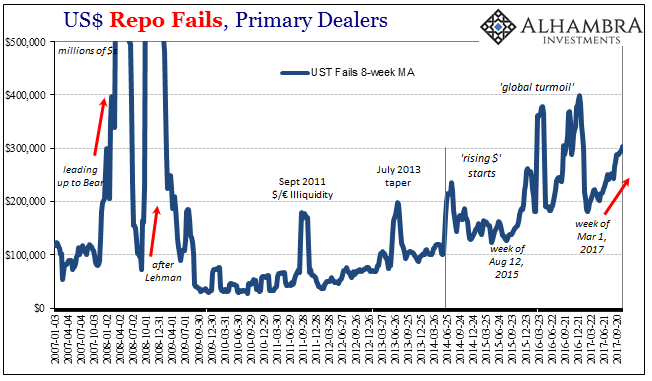

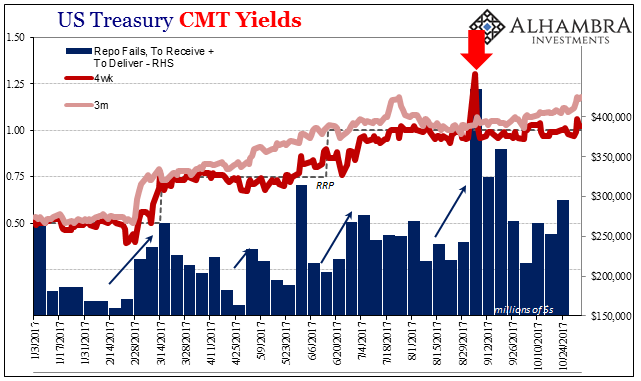

And like the repo market, it displays a clear lack of growth in collateral through one funding channel that used to be vital to growth in overall global “dollar” capacity. If the supply of collateral is as constant in being constrained as the TIC data suggests above, then any slight change in demand for particularly UST collateral against an inelastic supply could only lead to:

This is one part of what I mean by vitality in the banking channel that the non-banking channel just cannot make back up in whatever “other” it may be doing. Banks are dynamic institutions that were really set free by the eurodollar system to do all sorts of monetary and financial transformations way beyond the traditional maturity transformation of an old-style depository institution.

Among other things like derivatives, banks can manufacture and transform collateral. That’s exactly what they did in the middle 2000’s with MBS. It’s another matter entirely as to whether that was ever a good idea, for what we are dealing with now is the loss of the capacity to do it when it still remains a crucial systemic need. It’s not a funding process bank reserves could ever address.

It’s a net positive that they learned their lessons (or did they?) on stretching securitizations into subprime and whatever other “toxic waste”, but the ability and capacity to do so (in more than just repo and securities lending) kept the funding system growing in a way that allowed the credit system to create economic momentum (even if it was low quality). You can’t just remove one and expect the other to keep up with a growing economy’s needs. Instead, it becomes a severe global drag that imposes very real hardships on the whole system, money to economy.

Eurobonds are a possible alternate funding mechanism as are these non-bank participants. A foreign bank corporation can borrow dollars in that market just as well as a foreign industrial corporation. I have little doubt that in light of persistent eurodollar funding problems, that was the intent of China’s government floating a Eurobond last month – to set a favorable price for all the Chinese who “might” then follow.

But a Eurobond while delivering a balance of dollars is not a eurodollar. It is a lifeless, static dollar balance (taken at much greater cost) inflexible as to any kind of changing needs. The eurodollar system was, and still is to some degree, pliable at least in the bank channel basis for it. Whatever one bank might need another bank used to be able to dream up and then supply it. You just can’t get that from a bond offering or foreign MMF on strict mandate.

This is not, by the way, a defense of the eurodollar system at all. It’s merely an attempt to get behind the numbers in order to better describe (I hope) some qualitative contraction that’s deeper than the quantitative contraction (non-linear) readily apparent in these figures as well as a lot of others. The eurodollar system expanded to the degree it did because banks were like living things very adaptable to changing environmental conditions. That was huge especially given how the world has changed over the last fifty years.

The modern world especially in the 21st century was made out of eurodollars, with the banking system at the core of it. The bank channel continues to retreat in capacity and what’s being lost is more than just eurodollar deposit balances or even repo collateral flow (and might account for why the monthly TIC bank liability estimates are now so noisy). There was a living element to the global system that is no longer so lively, or so adjustable to its own decay. It’s capacity that’s not easily replaced and cannot be ignored.

A dynamic system easily solves and overcomes problems; an increasingly inflexible one increasingly can’t handle what used to be nothing more than minor disturbances.

Stay In Touch