The former Federal Reserve Chairman doth protest too much, methinks. The answer to why Ben Bernanke is still defending QE is obvious. Had it worked, I mean really worked, he would be today universally hailed as the greatest monetary steward since Bagehot. Though he wrote a book trying to cast himself in that way, the rest of the world just isn’t seeing it, or buying it (which way Treasury yields?). Thus, he protests; a lot.

For QE to be debatable after so long and so much of it tells you everything you need to know about its effects. There were some, they think, but even proponents can’t really tell you with conclusive vigor what they were. Instead, as Bernanke writes in his latest paper, published in early October:

Consequently, disagreements remain among researchers about the magnitude and persistence of QE effects and about the relative importance of the two primary channels of effect.

Bernanke’s emotional insecurity is on full display with what he immediately writes after the sentence above. “Nevertheless, the strong view that QE is ineffective has been pretty decisively rejected.” By whom? If that was true Bernanke wouldn’t be writing this paper to defend the weakest of QE’s presumed positive effects.

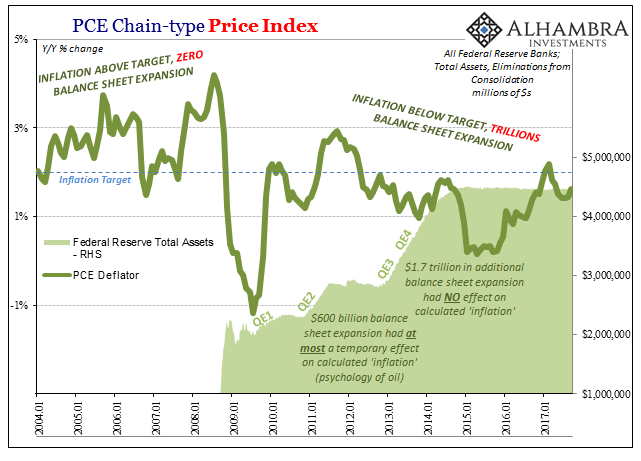

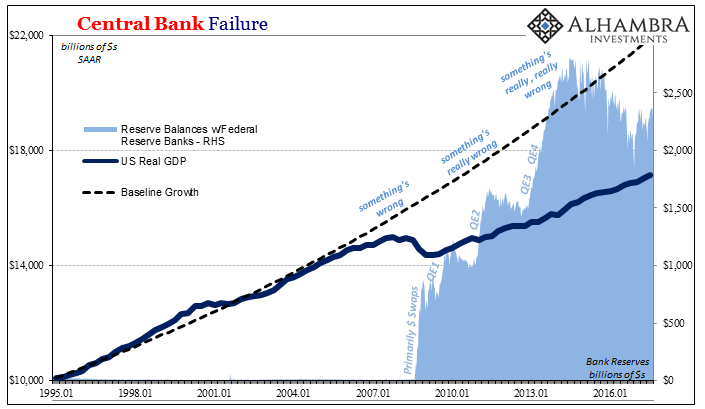

If QE had worked as advertised, there would have been full recovery. Full stop. That didn’t happen, so Bernanke and all the rest of the world’s central bankers have enough sense not to really bother with holding themselves to their own prior standards. They now know, after enough time, they can’t.

Instead, what they are doing is trying to work backwards to find anything. QE didn’t create a full recovery, or a partial one, it didn’t lead to a breakout of inflation, or even behaved inflation conforming to explicit targets, but it must have done something, right? Absent second and third order effects, which is right where success would be, Bernanke is left to examine at least some first order stuff (and still, as noted above, there isn’t agreement as to how much good might have been done even here).

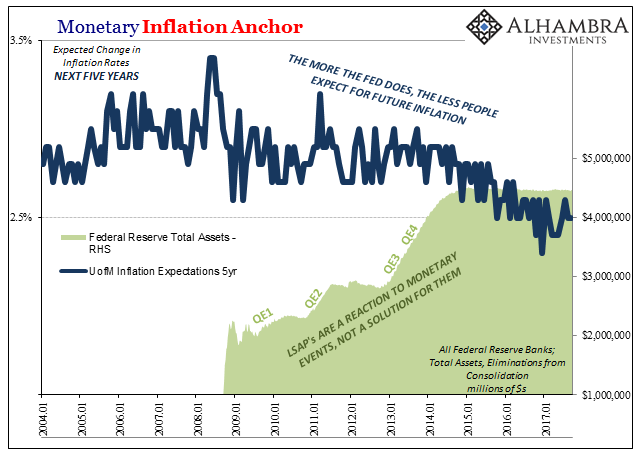

Essentially, QE was meant to work through two primary channels, and it was always described in this way. The first is the signaling channel and is really about expectations. As Bernanke writes, “The signaling channel arises to the extent that asset purchases serve to demonstrate the central bank’s commitment to monetary easing.” It is most self-fulfilling in that “easing” becomes a term of art not science. As noted yesterday, if you want to believe central banks are printing money because of what they are doing, then that’s part of the signal affecting expectations.

The other channel is the portfolio one, or portfolio effects. This is much simpler and more tangible. The Fed buys UST’s from the market taking that many out of the supply, forcing market agents to buy other securities rather than UST’s. That raises the price of those other things, all else equal, delivering stimulus to the economy.

Thus:

QE has been found to have significant effects on both rate expectations and term premiums, suggesting that both the signaling and portfolio balance channels are operative (Bauer & Rudebusch, 2013: Huther et al., 2017). And, although showing direct links to macroeconomic outcomes is not straightforward, the experiences of the U.S., U.K. Japan, and Europe all suggest that the use of large-scale QE has been followed, over the subsequent couple of years, by strengthening aggregate demand and improved economic performance.

That is the best he can manage in defense of four large QE operations and seven years of ZIRP. That’s it. The “experiences” “suggest” “over the subsequent couple of years” some macro performance that is maybe somewhat positive. Perhaps, but that’s not what most if not all Americans thought was going to happen as a result.

In many ways this is all a wasted exercise, almost completely pointless. The real purpose in raising this particular paper from my end (and thanks again to T. Tateo for unearthing it) is that Bernanke is debating QE, even though it doesn’t go all that well for him, on his own terms. There’s a whole lot missing here and so long as it remains missing so, too, will the real recovery .

In truth, QE was dead in the water from the beginning. It had no chance of success. The reason relates to “easing.” The last ten years have shown, conclusively, that expectations aren’t nearly enough to foster economic growth (consumer sentiment and spending, for example, bear little relationship with each other anymore). What good is it to try to influence inflation expectations if there isn’t in the end any inflation?

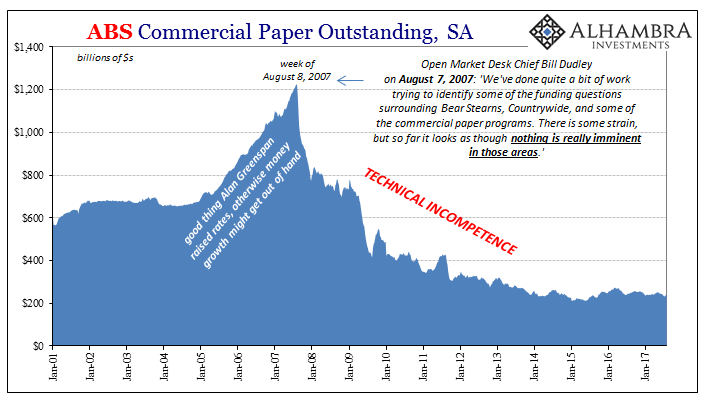

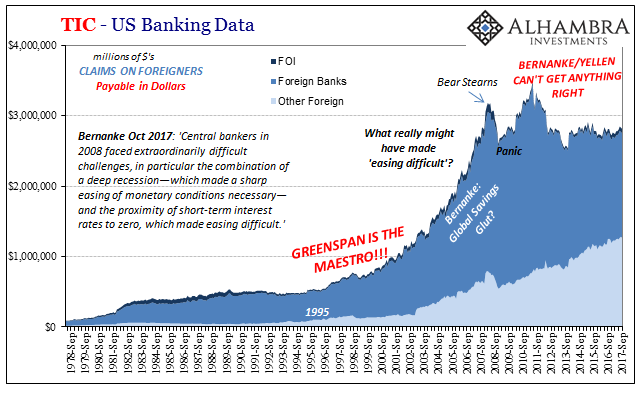

Bernanke’s undoing, the thing that eventually people will truly lament about his tenure, is “subprime is contained.” These are more than famous last words, though recalling that particular statement is a cheap shot, no doubt, but one he as Fed Chairman thoroughly earned. He writes today of this dilemma in which somehow the central bank is also a victim of circumstances:

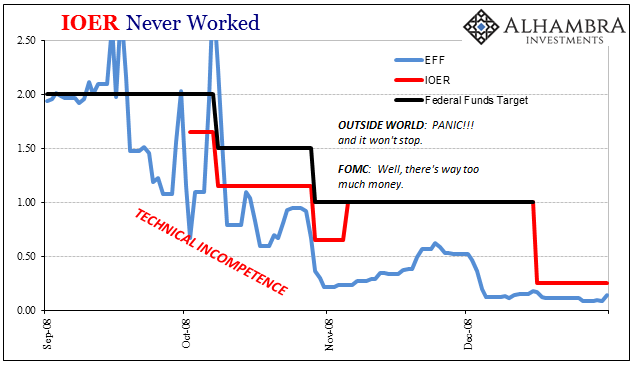

Central bankers in 2008 faced extraordinarily difficult challenges, in particular the combination of a deep recession—which made a sharp easing of monetary conditions necessary—and the proximity of short-term interest rates to zero, which made easing difficult. In response, monetary policymakers employed a number of unconventional policy measures.

We may be seeing a repeat of what has become a staple of orthodox Economic history. Since so much of Economics is predicated on later lessons gleaned from historical reviews of the Great Depression, there has been a tendency to overlook anything and everything that happened before October 1929.

Here it is again, only in the 21st century it starts with Bernanke talking about his actions as Fed Chair as if they all began in December of 2008 with the introduction of ZIRP and QE. He starts off his story toward the end of the crash as if the crash was some otherworldly thing to which nothing could have been done to fix it.

That’s not necessarily true, nor is it what he said in the year and a half leading up to the major emergency monetary policy measures. He said “subprime was contained” for a reason, meaning that the Fed believed it could as it was supposed to forestall any monetary event of sufficient magnitude. Panic was at that time thought impossible (we know they believed this because all their models claimed that was the case). That’s exactly how the central bank, indeed all the central banks, proceeded and it proved almost immediately to be wholly false.

Even from the signaling channel, can he be so arrogant so as to not believe the Fed’s failures up to and into the crash were not factored into post-crisis expectations? Seeing the Fed fail once is such spectacular fashion is a wake-up especially since most market participants started out taking him at nothing more than his word for “subprime is contained.”

No wonder Day Zero in this revised policy review is QE1; it’s easy to compare to the absolute worst and then claim the minimal progress since then is both progress and yours.

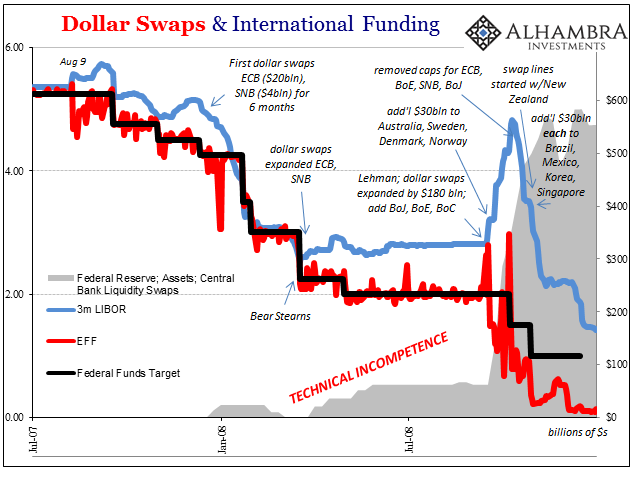

The very fact that there was a monetary event that caused the Great “Recession” is itself the reason for QE’s subsequent failure. It was all one single failure, both before and after. The story of eurodollars and bank reserves, or at least the latter’s noted absence, is that entire difference. Until someone makes sense of 2008, not just attempting to justify 2009 forward, there isn’t going to be any progress. We still talk about 2008 because we aren’t yet done with 2008.

For Bernanke, that means forgetting 2008 and hoping you do, too. Somehow, he has been afforded that luxury. We haven’t been. It’s really that simple. They really don’t know what they are doing. After ten years, it’s become more difficult for them to hide that fact.

Stay In Touch