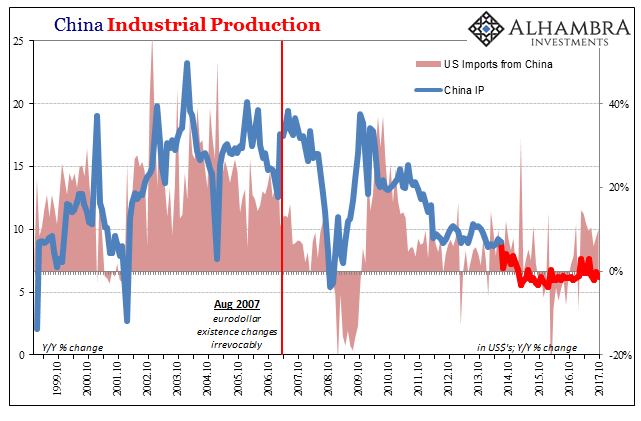

There are two possibilities with regard to stubbornly weak US imports in 2017. The first is the more obvious, meaning that the domestic goods economy despite its upturn last year isn’t actually doing anything positive other than no longer being in contraction. The second would be tremendously helpful given the circumstances of American labor in the whole 21st century so far. In other words, perhaps US consumers really are buying at a healthy pace, just not with the same eagerness from China and the rest anymore.

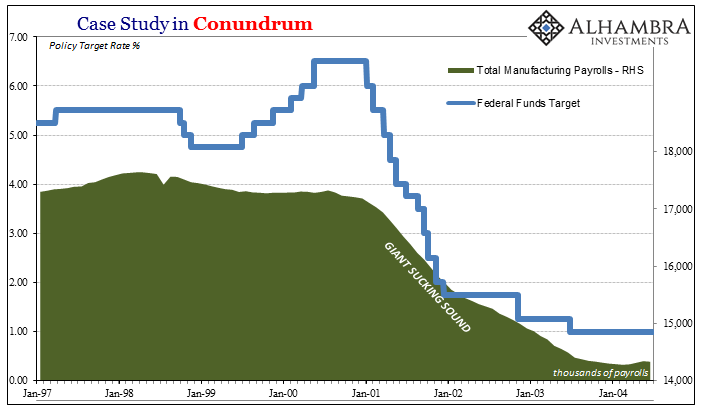

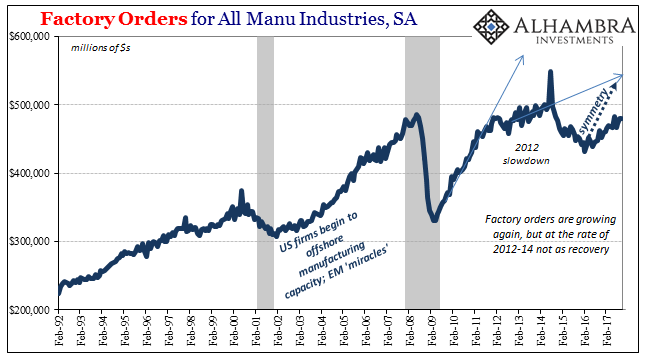

It was during the dot-com recession of 2001 that Ross Perot’s “giant sucking sound” finally materialized. Between then and the bottom of the Great “Recession”, one third of US manufacturing jobs disappeared. With imports stuck, especially those from China, could production be moving back onshore? The unemployment rate at 4.1% would seem to suggest a burgeoning economy where that might be the case for US consumers.

Unfortunately, that doesn’t appear to be happening according to any data. Despite it being a Trump campaign promise, there just isn’t any indication that the loss of manufacturing capacity is anything other than permanent. Then again, we don’t really know for sure because there just isn’t any growth in the demand of US consumers regardless of where the goods are produced.

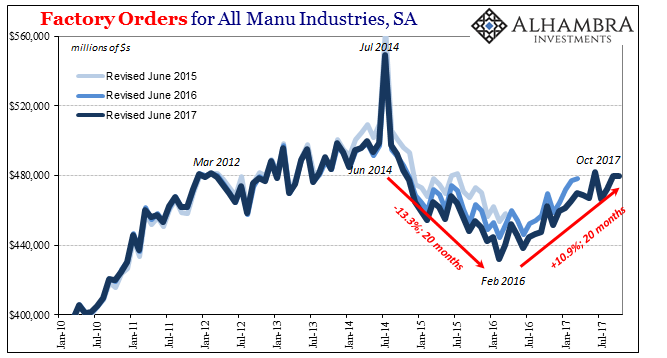

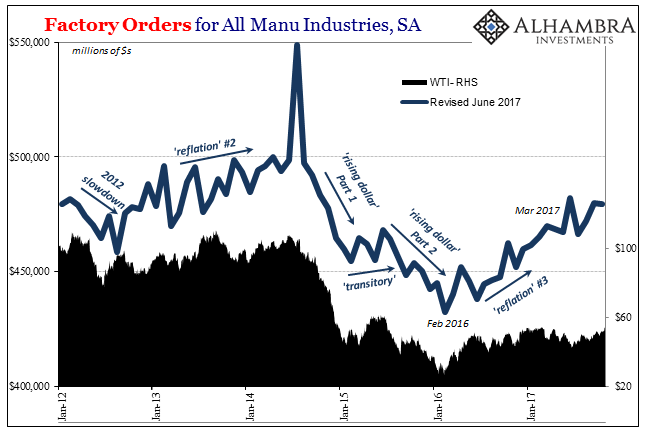

To that end, US factory orders were up a mere 5.2% year-over-year (unadjusted) in October 2017. After contracting for just about two years, the domestic factory sector is as moribund as its Chinese counterpart for the same reason – the absence of upturn, real upside, from US consumer demand.

On a seasonally-adjusted basis, factory orders declined for 20 months (starting in June 2014, disregarding the Boeing-related surge that July) before finally hitting bottom with everything else in February 2016. In that time, factory demand fell off by a little more than 13%.

With the latest update for October, there is now 20 additional months of “recovery” since that low, giving us in terms of the calendar a measure of symmetry. In that time, orders are up just 10.9%, leaving US factories with significantly less forward demand in October 2017 than three years earlier.

This is not typical of any cyclical process, where symmetry demands at the very least a sharper upturn as compared to the downturn preceding it – so that whatever economic account doesn’t merely equal that prior peak in about the same amount of time but actually grows fast enough to retrace to the prior trend.

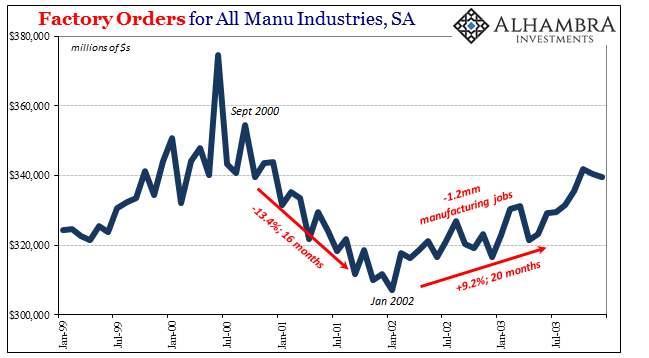

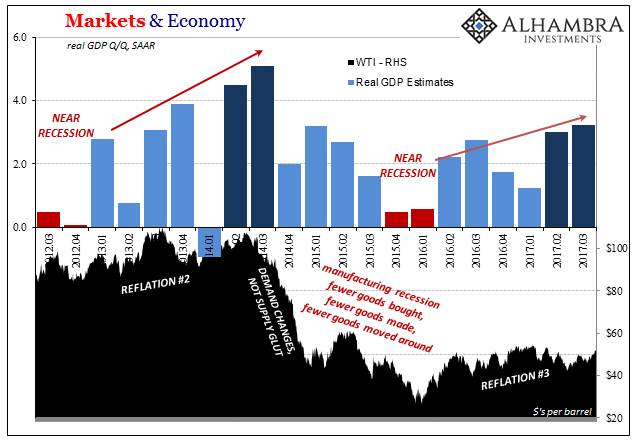

This half recovery isn’t without precedence, though, including just this data series. Into the dot-com recession, factory orders (on a seasonally-adjusted basis) declined for sixteen months between September 2000 and January 2002. During that time, orders dropped by almost the exact same relative amount (-13.4% vs. -13.3%).

And in the 20 months following, during what was supposed to be a recovery, factory orders also seriously underwhelmed. They rose by just 9.2% during that same timeframe, leaving the US factory sector after three years significantly less than when the whole thing started.

While that sounds eerily similarly as what has taken place over the last few years, there is an enormous difference. In the early 2000’s there was an obvious reason for the weakness. Not only was the dot-com recession a declared cycle peak, the prolonged softness in the upturn after it was attributable, again, to the giant sucking sound of US manufacturing capacity disappearing from our shores. In those same twenty months of suspiciously slow recovery, a further 1.2 million manufacturing jobs were cut.

If the US factory sector in 2014-17 is performing about the same as during the giant sucking sound, what can possibly account for it today? The only answer is what the yield curve is saying, not what the unemployment rate does.

While the 2015-16 downturn has yet to be made under an official NBER declaration, and probably never will be, for the manufacturing sector (and a good deal more) it was a recession all the same. What has followed from it is not the same loss of manufacturing capacity, meaning supply, but instead consumer capacity for demand. The giant sucking sound this time is not just the shrinking of US industry, but now the shrinking of the whole global economy. The eurodollar financed this redistribution of economic terms in the early 2000’s, proving Ross Perot belatedly correct, but now it benefits no one anywhere.

Stay In Touch