When we look back at the period known as the Great Inflation there is a tendency, I believe, to truncate the episode only to the most well-known parts. What many people remember are things like gas lines, where oil problems and embargoes left Americans at several points in the seventies too often stuck for trying fill up their autos (or just the household lawn mower).

It’s very easy, then, to fall into the assumption that the Great Inflation was mostly petro issues concentrated in the 1970’s. Those were, in fact, symptoms of a greater problem that began actually in the mid-1960’s.

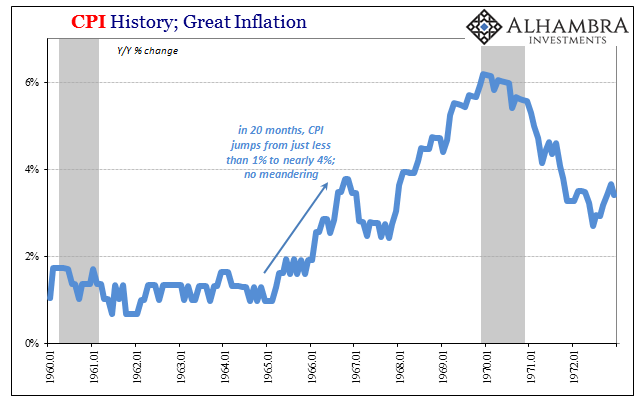

For the first part of that earlier decade, consumer prices remained low and stable. Around 1965, however, they jumped in sustained fashion. The reasons for the Great Inflation are several, including the growing acceptance of the exploitable Phillips Curve offered by economists Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow. The idea was that the government might trade off inflation for employment, tolerating more of the former to “buy” less unemployment.

Alan Meltzer’s fabulous history of the Federal Reserve identifies the central bank’s legacy “even keel” policy as one of the proximate causes, too. Owing to lingering commitments from when the Fed was obliged to place a ceiling on UST rates, after 1951 it no longer entered the government bond market for that reason but it still increased the level of reserves ahead of each treasury auction so as to guarantee smooth function. At some sufficient period afterward, the Fed would then drain reserves to balance out.

In 1965, the Johnson Administration decided in part due to Samuelson and Solow to pursue both the Great Society as well as communists in Vietnam. The exploding budget deficits spooked markets (the remnants of Bretton Woods) while also forcing the Fed into constant reserve liquidity; treasury auctions became so frequent and large that there was simply no time to remove so much “accommodation.” It simply built up until it was far too late.

I would also submit the radical global monetary changes presented by the eurodollar system, those that confused and misled especially monetary officials into these same types of mistakes.

There was a combination of very specific reasons that all had the one thing in common – clear and uniform monetary increase. The direction of the money system globally was never in doubt, which makes the resulting fifteen years of debacle that much more disgusting. Economists just aren’t good at economic management, though they never stop trying, a flaw both in their designs as well as unearned hubris in the face of complex systems.

In a space of just 20 months starting in March 1965, the CPI accelerated from less than 1% to just about 4%. By the dawn of the seventies, the CPI was already running at 6% that only the severe recession of 1969-70 could temporarily halt. By early 1974, the CPI was right back at, achieving double digits; no meandering anywhere.

The subsequent rise of unemployment due to the imposition of the business cycle in 1969-70 at that point started off what people recall most about that time – the concurrent increase of unemployment and inflation. Stagflation. Samuelson and Solow were wrong, as Milton Friedman contemporarily pointed out, but it was money growth in qualitative ways as well as quantity that began the process.

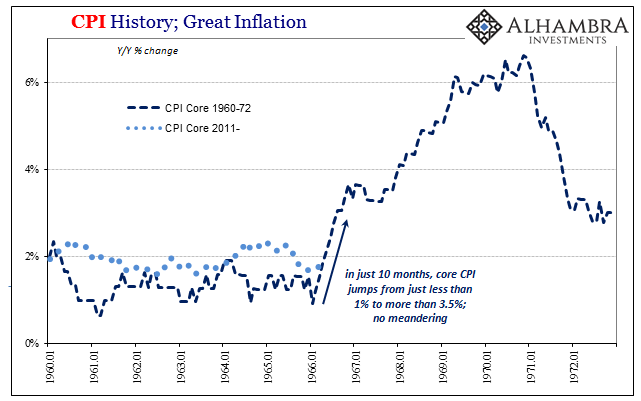

In those early days of the Great Inflation, it was a broad-based rise of consumer prices that would lead to disaster. Despite impressions of OPEC drama and gas lines, in the second half of the sixties the emphasis through prices wasn’t really oil-based. The core CPI, for example, records that it was everything in motion rather than a single part or segment of the so-called consumer basket.

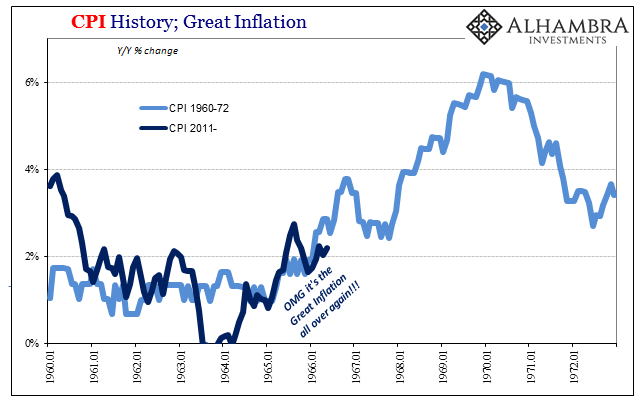

Many people in the 21st century as a result of seeing QE as money printing have predicted similar trends and results, a rerun of the Great Inflation as the irresponsible monetarism of Large Scale Asset Purchases eventually seep out into the real economy as even keel, the exploitable Phillips Curve, and missing money once did.

In November 2010, two weeks after the FOMC voted for a second round of QE, twenty-one prominent economists and government officials wrote an open letter to Chairman Bernanke urging him to reconsider.

The planned asset purchases risk currency debasement and inflation, and we do not think they will achieve the Fed’s objective of promoting employment.

They were right about the second part, the labor market still missing some 16 million Americans even in 2017 as well as reasonable growth, but the reverse happened with respect to the former. The dollar did not go down (something about it rising?) and consumer price inflation rather than explode as it did five decades ago went the opposite way. According to the PCE Deflator, the central bank’s standard for such things, the Fed has undershot it’s explicit 2% inflation target for five and a half years and counting.

Still, with the unemployment rate now down to 4.1% that hasn’t stopped the inflation fears from being offered yet again. This time they are being driven largely by Fed officials, who are now desperate to get back on track with some version of consumer prices since that would be at least one sign they achieved something. They have been predicting so-called cost-push inflation through wages for years now as the result of successful monetary policy largely in the four QE’s.

In late February this year, FRBNY President Bill Dudley (it’s always Dudley) went on CNN and said, “There’s no question that animal spirits have been unleashed a bit post the election.” He and his fellow FOMC compatriots then spent the balance of 2017 so far wondering where they went.

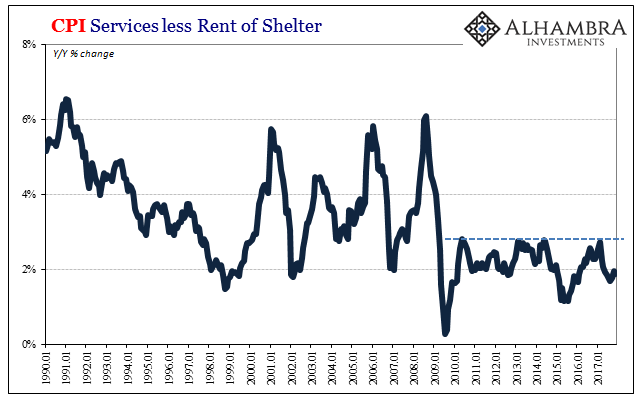

Unlike the mid-sixties, the only thing driving inflation indices right now is the price of oil; and not even that, it’s merely the base effect of oil prices being somewhat higher now than from lows in the year ago lookback. There is no broad-based indication of rising let alone out of control consumer prices. Despite CPI Energy being up almost 10% year-over-year in November, the headline CPI remains at just above 2%. The core CPI rate fell back to 1.7% again.

These specific views of the CPI stripping out volatile energy prices indicate nothing like animal or monetary spirits. They suggest less price pressure today than when Dudley spoke about such economic success, and significantly less than the pre-crisis period. Core rates like these suggest what the labor market data does outside of the unemployment rate – there was no recovery, not then and not now.

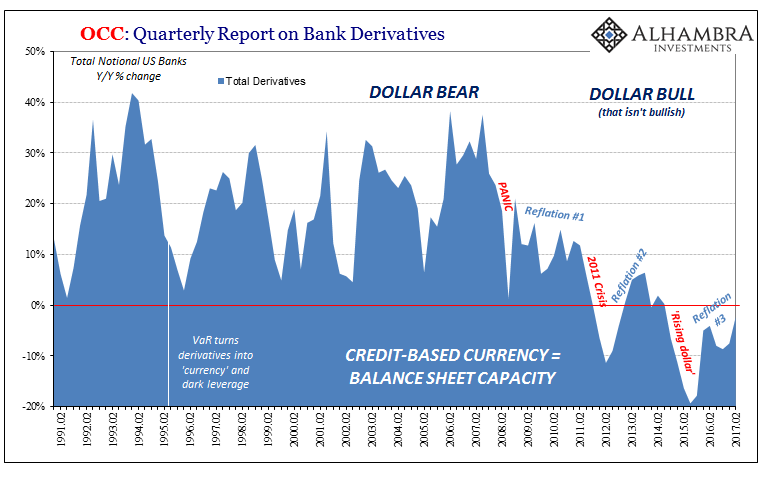

One primary reason, if not the only reason, is that QE was never money printing to begin with. Unlike fifty years ago, the global monetary system is uniform in its indicating grave money supply issues in the other direction – a constant shortage of effective “dollar” capacity which is why the dollar rose rather than fell (check out basis swap premiums since repo fails surged in early September).

The only animal spirits that have ever been unleashed during this “recovery” are those lingering in the minds of people often “experts” who don’t know how to define money let alone money printing. There is, in fact, only one common element between the last ten years of a lost decade and the decade and a half of stagflation during the Great Inflation: they really don’t know what they are doing. The consequences of that turn in both directions.

Stay In Touch