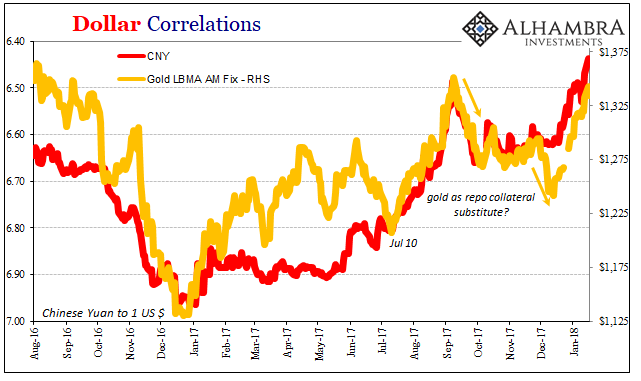

What determines the price of gold? It seems like it should be an easy question to answer, but gold more than perhaps any other asset often mystifies in its behavior. Part of the reason is mainstream, orthodox Economics and its practitioners who have waged an intentional war on the metal for more than a century and a half. Demonizing it has effectively meant a lack of fundamental study.

That’s true, of course, about a whole lot more than the marginal setting of the gold price. Economics simultaneously devalued money as a concept in order for it to fit in DSGE models without producing singularities in all the complex math. Like rational expectations theory, demonetizing money, so to speak, places econometrics above rational understanding, substituting determined ignorance for appreciating what is very messy, and unpredictable, reality.

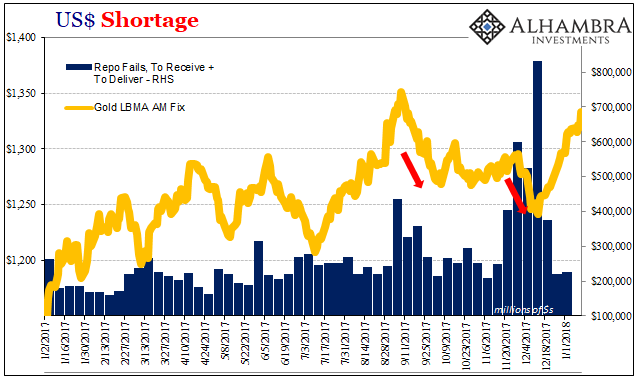

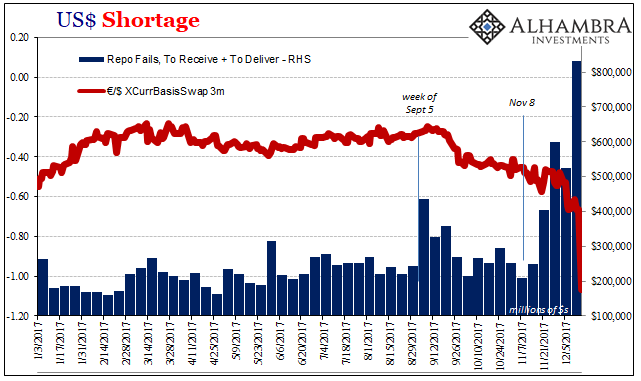

One silver lining from an otherwise thoroughly disappointing 2017 (it was supposed to be the year for economic expansion, real economic expansion, but now that’s 2018) was another obvious test for what possesses gold at least in specific episodes toward the downside. Later in the year, for the second straight year, repo collateral became hard to come by, a serious defect that spilled over into other funding markets and capacities – including gold as collateral of last resort.

In that weird way, the Federal Reserve should be gold owners’ best friend; a functioning and useful RRP would alleviate these persisting gold slams. The reverse repo, however, has been one more fairy tale Economists recite in the media for why central banks are for them so central.

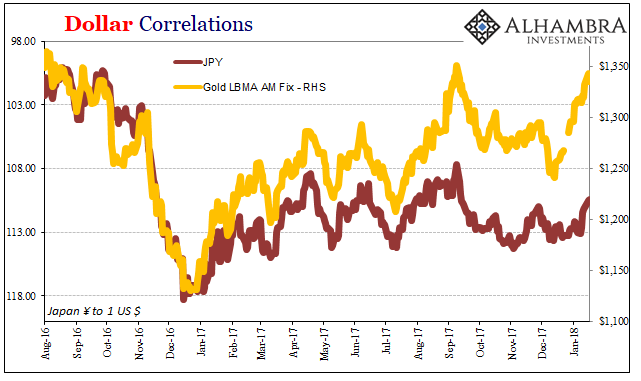

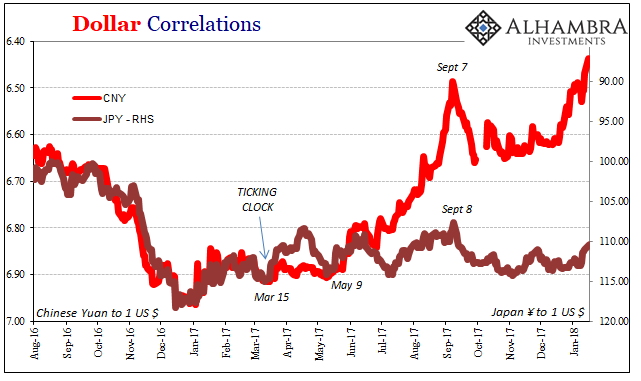

For several years, the gold price in dollars correlated strongly with Japan’s currency far more than our own. You hear all the usual explanations for what sets gold prices altered slightly to try to explain this, from interest rate opportunity costs (gold pays no interest) on safe assets to expected inflation to several other alternate theories floated over the years. Many of those latter ideas have been expressed to try and account for JPY’s hold.

“The yen is viewed as a liquid safe-haven alongside gold,” Osborne said. “The U.S. dollar gets less of a bump in times of uncertainty because much of that geo-political concern is U.S.-centric, especially since November.” Both the yen and gold have strengthened this year, with bullion rising almost 10 percent.

Another explanation is that both the Japanese currency and gold are closely correlated with U.S. 10-year treasuries — when yields fall, the yen tends to strengthen, and falling yields mean a lower opportunity costs of holding gold, which also boosts prices of the metal.

That article was written back in May 2017, just as the correlation was still close to its apex; from that point, it started to break down where gold exhibited all of a sudden a much higher beta than JPY. Again, this was a long-term relationship that had by 2016 gained a whole lot of attention for good reason.

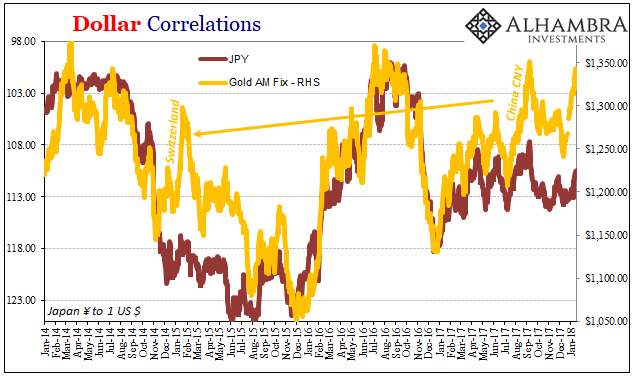

The yen has been at the center of a lot of things over the past years, particularly those of the “rising dollar.” This isn’t surprising to those who follow wholesale FX patterns, for what was equally clear in them was the central, vital position of Japanese banks in redistributing “dollars” all over the world (a position they have held to varying degrees going all the way back to the earliest days of the eurodollar market). For many reasons, Tokyo had in the aftermath of 2008 become the “dollar” basis especially for China.

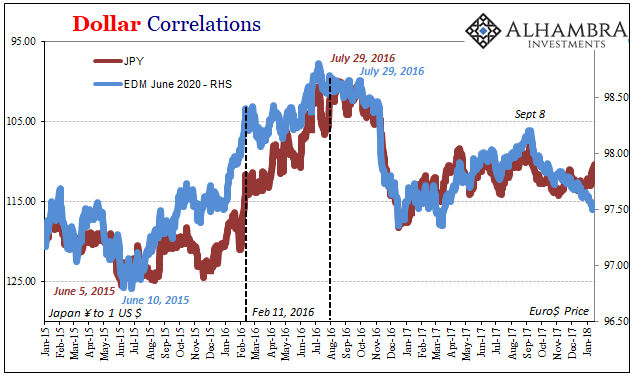

But as gold starts to break from JPY, we can’t help but notice that other correlations have faltered in recent months, as well. Yen and eurodollars futures, for example, weren’t as tight as JPY/gold but it was close. There had been a clearly established mutual pattern for most of the past four years for all the same reasons.

That has changed going back to early last November. As you can plainly see above, EDM and JPY are moving in opposite directions these days. It had been for a very long time a daily rule of thumb that before checking anything else you could tell what funding and bond markets were doing by yen alone; if JPY was up in early Asian trading, you could count on eurodollar futures prices to be up, too, or UST yields to be lower.

For the past two months, however, EDM and JPY are moving almost against each other – as have UST yields. With yen exchange moving higher yet again toward 110, the UST market has exhibited a more determined tendency toward selling than buying as had been the case for years.

What has changed?

One potential answer might be the Fed. They are running off their balance sheet at the same time “raising rates.” In theory, that shift could serious alter the perhaps delicate dynamics holding all those correlations together. The problem with that theory is, obviously, that it depends on the US central bank being relevant to actual eurodollar operations. That just hasn’t been the case.

If we instead look for more forthright and immediate correlations perhaps aligning far better with the changes noted above, we can’t look anywhere other than Hong Kong.

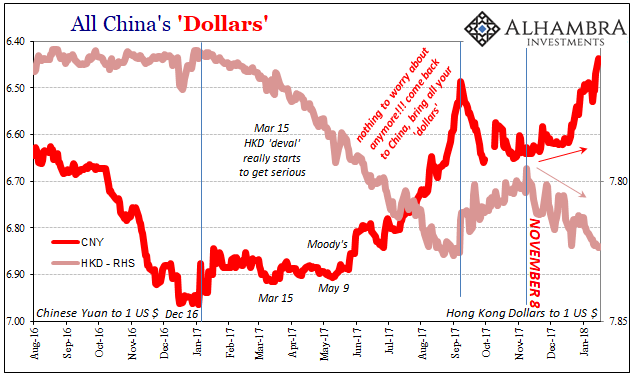

The other condition clearly established during the disappointment of 2017 beside gold and US$ repo collateral was China’s “dollars” in and out of Hong Kong. There can be no doubt any longer, especially after November 8 when this latest flow began (or was restarted). Not only was that around the time when the global FX basis for US$’s began to alarm, it was then that repo fails started to rise for a second time and, as noted above, EDM broke in the opposite way from JPY.

What it all suggests is that Japan might not any longer be so crucial to China’s ongoing “dollar” problem. In its place, at the margins, Hong Kong banks appear to have been substituted for Japanese firms. From the Chinese perspective, you can, I hope, understand why as well as the difference. Hong Kong may own a separate currency/monetary system, but it is still China. And the latter’s global monetary reputation made it, apparently, too tempting to resist two decades of promises not to intermingle.

I believe, in broad terms, that’s why CNY’s direction has been both sustained and received like “reflation” rather than JPY-driven anti-“reflation” of earlier in 2017. For one, JPY and CNY starting to diverge right at the last “ticking clock” striking zero:

Rather than pull JPY up with it, which would have been the direction of lower UST yields and higher eurodollar futures prices, CNY over the summer instead dragged HKD into its orbit for the first time (leading to an enlarging mess in HKD apart from the currency exchange rate). That, to me, marks the beginning of the big change; the events in September, the hardening of the transition so that by early November Japan while not completely off-the-hook for China has become secondary to Hong Kong in the eurodollar redistribution order.

The further breakdown of correlations simply confirms what we already know via HKD’s (and HIBOR) unusual behavior. As I wrote last summer, Hong Kong isn’t supposed to be exciting let alone the slightest bit interesting; which is exactly why it has proved to be irresistible from the Chinese perspective, either officially or in desperation derived from the huge “dollar” requirement emanating from China’s vast corporate sector (especially financials).

In talking with my colleague Joe Calhoun, we both can’t help but notice that in several key markets (futures) the extreme positions on every side. I think this is a big reason why, a possible paradigm shift that represents a whole lot of hidden and/or misunderstood risk in addition to correlations coming apart leaving traders unable to anchor their views and bets as they had for a very long time. It was easy to trade gold with JPY, or EDM, but now? Who trades with Hong Kong? How?

As always, there are other moving parts to consider, too. I’ll take a look at those in the coming days.

Stay In Touch