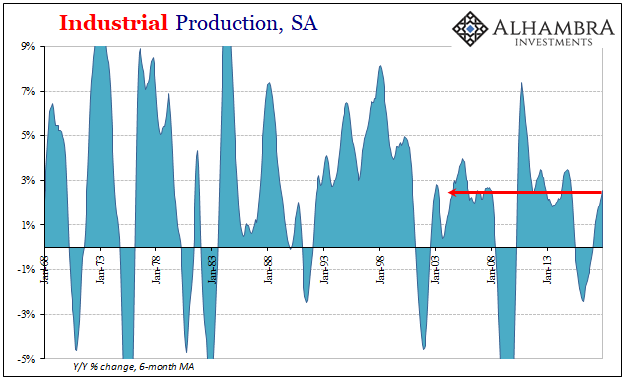

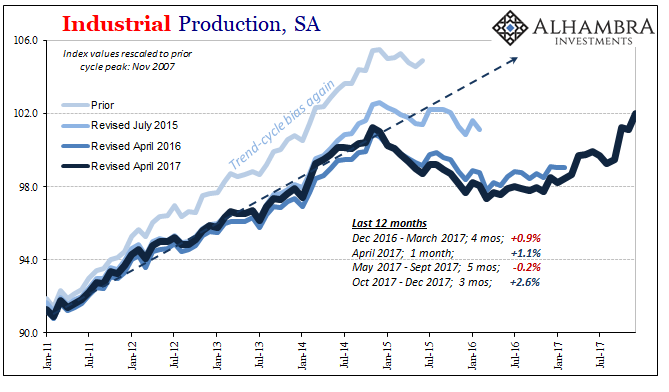

Industrial Production in the US was up 3.6% year-over-year in December 2017. That’s the best for American industry since November 2014 when annual IP growth was 3.7%. That’s ultimately the problem, though, given all that has happened this year. In other words, despite a clear boost the past few months from storm effects, as well as huge contributions from the mining (crude oil) sector, American production at its best can only manage to reflect 2014.

There are, of course, three main components of industry: manufacturing, mining, and utilities. When we think of the tangible economy, most often we go right to manufacturing first if not also exclusively. In 2017, however, the manufacturing part of IP gained just 2.4%. That’s not good; at all.

Utilities were up only 1.8% year-over-year, with almost all that growth piled just in December 2017. Accounting for the overall IP index’s increase month-over-month, unusually cold weather meant for US utilities a 5.6% increase in output from November.

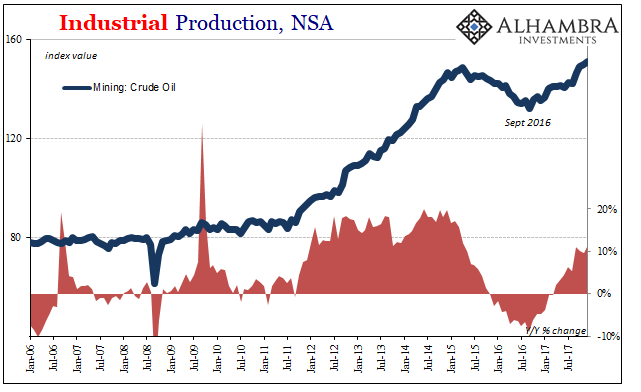

That left any additional growth above the low level for manufacturing to the mining sector. With oil prices steady to higher for especially the second half of last year, the output in resource extraction climbed 11.5% year-over-year.

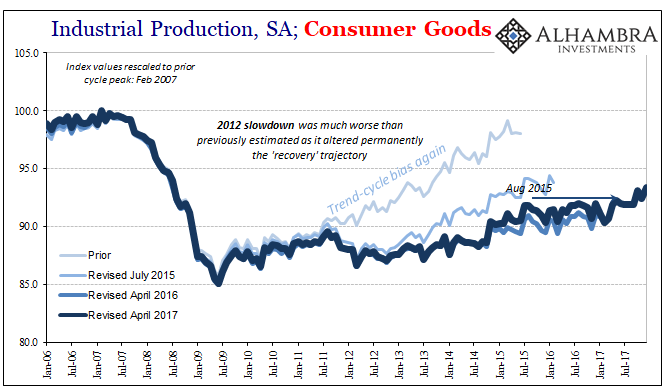

In that sense, we really are back in 2014 again. After all, three years ago the energy piece of US industry performed a similar skew to these kinds of metrics. US manufacturing continued to be moribund if at least positive, though still very much unrecovered from the Great “Recession.” It was the shale boom then largely responsible for partially covering up an otherwise shrunken industrial base in manufacturing.

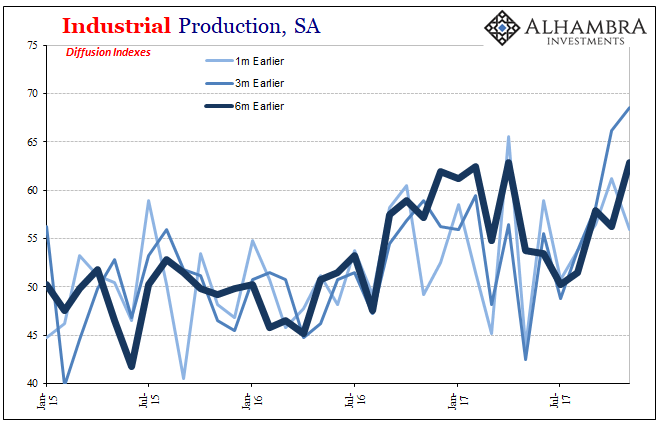

That condition never really changed throughout the downturn 2015-16. In fact, after a relatively small and brief rebound the second half of 2016, up until September/October 2017, US industry was in relapse. The Fed’s data is universal in describing what was for several months prior to Harvey and Irma outright contraction across the industrial sector.

That’s unusual for any growth period, to say the least. It was recorded in the Fed’s diffusion indices (these are almost like a PMI; survey respondents are asked whether their level of output is more or less than 1, 3, and 6 months ago) as quite severe.

It has only been in the aftermath of those hurricanes that industry staged its turnaround. Even the overall IP index, which includes both utilities and mining, has exhibited this atypical lumpiness. Thus, we have to ask the question what would Industrial Production look like without the artificial boost in October/November?

Since nearly all the yearly gain was produced in the last three months, and half of it from October alone, it’s a relevant question for 2018. The media has predictably gone completely off the rails again just like it did in 2014, when any level of growth was characterized as massive. It produced then, and produces now, some strange dichotomies that are only strange if you believe the rhetoric without context for these and other numbers.

For one example:

The world economy is taking off, factories are humming again and copper futures prices are jumping. The one thing that’s missing is buyers of the actual metal.

Bloomberg noted a week ago (h/t M. Simmons) that copper prices are up on paper speculation alone. To the author of the article, that seemed a big mystery with what’s reported in the mainstream to be a massive boom underway. Don’t worry, we are told, all that physical buying is coming “sooner rather than later.”

But if you reexamine all the assumptions in that first quoted sentence (including whether copper prices are really jumping; they are up, to be sure, but like a lot of other things are only up compared to the bottom and nowhere close to the last top), maybe what is being reported is instead just purported based on emotional rather than rational analysis. It’s the same underlying theory of “globally synchronized growth”, meaning that people expect after a decade growth has to happen because it has to happen.

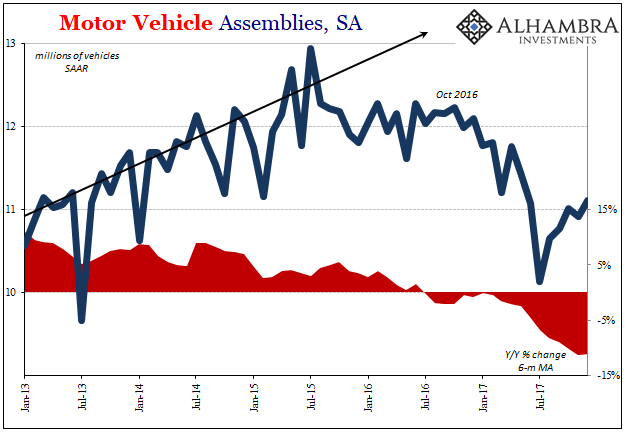

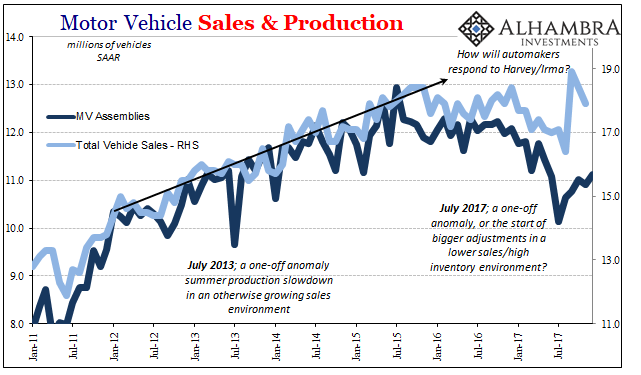

One primary piece of manufacturing and therefore industry that is absolutely not booming is autos. Motor Vehicle Assemblies, the Fed’s Industrial Production proxy for domestic car production regardless of the name on the vehicle, were just 11.1mm in December. For 2017 as a whole, every month in it came in at less than 12mm, with a very steep drop-off in July at model yearend production closeout. These factories are un-humming now for more than a year, suggesting this is no minor, random fluctuation.

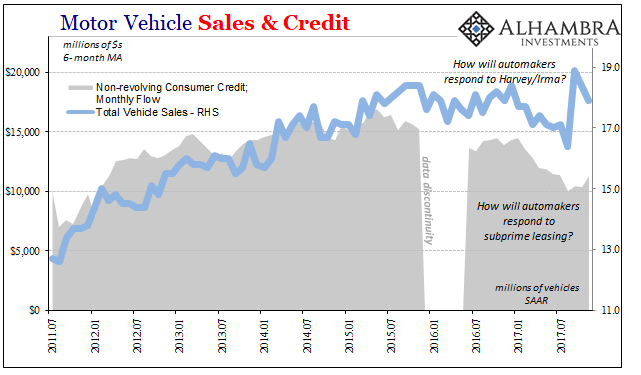

The auto sector isn’t as vital to the US or global economy as it was a hundred years ago, but given that for most of the “recovery” after 2008 it had been the one segment that was actually robust, it’s struggles going on now for a third year can’t be just ignored. That’s largely because there is consistency in that state top to bottom – auto sales to auto inventories to low levels of production with further downside risks.

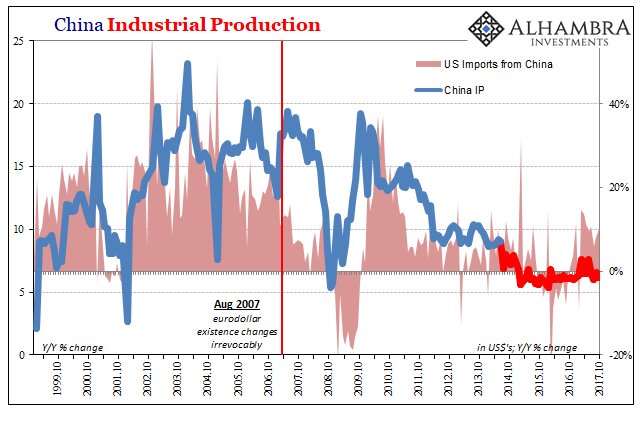

Even marginal non-revolving consumer credit fits the pattern (acknowledging that the Fed’s data on consumer credit includes other forms, such as student loans, in that wider category). If there is no boom here, there is no boom in China where the price of copper and even “reflation” itself is derived.

Nowhere is there indicated “factories are humming again” except if you concede to the author of the phrase a high degree of poetic license. A very high degree. Even with the renewed shale boom, that actually is one, US industry overall remains far short of normal.

While mainstream economic magniloquence continues to be the common order, there is every other reason to suspect 2018 begins more like 2017 was in its middle portion. It’s an assessment that is appropriate for much more than US Industrial Production. Given that the near-recession is now two years in the past, we should be starting this year on a completely different footing than the past few. We’re still stuck with “green shoots” and nothing more; worse, it’s those that are now classified as “the world economy is taking off.”

Stay In Touch