As most people know, the Kansas City Fed has been holding its annual symposium in Jackson, WY, for a very long time. Supposedly a draw for Paul Volcker’s fly fishing hobby when he was Chairman, the conference came to include heavyweights on a regular basis. Most of them, especially those in the early years, however, were duds.

It wasn’t until 1985 that there was anything of real substance discussed, the topic finally the dollar six years after its great crisis had concluded. The most notable contribution to that one came from Paul Krugman who started his presentation noting that he was for five years by then confused and befuddled by its movements. Some things, it seems, never change (including those who refused to listen to Robert Solomon, also there in ’85).

One of the more interesting gatherings took place in 1999. The year and the reasons need no introduction. What most people remember about 1999 can be summed up by the acronym NASDAQ. Try as they might, even central bankers and economists were feeling some desire, maybe need, to address the situation.

The line up was a who’s who of top tier Economists: Alan Greenspan giving the introduction, Allan Meltzer talking zero inflation, Martin Feldstein fretting about currency, and Stanley Fischer actually recalling, “Well, everybody has his or her own view of what it is that Adam and Eve did in the Garden of Eden. Mundell’s version is that the original sin was that Eve told Adam about central banking, about the notion that you can create value with a stroke of the pen.” On top of all that there was the obligatory paper from Ben Bernanke (co-author with Mark Gertler).

While not all talked about or focused on the dot-com bubble, the topic in general could not be avoided. Bernanke’s position was easily summed up:

The principal conclusion of this paper has been stated several times. In brief, it is that flexible inflation-targeting provides an effective, unified framework for achieving both general macroeconomic stability and financial stability. Given a strong commitment to stabilizing expected inflation, it is neither necessary nor desirable for monetary policy to respond to changes in asset prices, except to the extent that they help forecast inflationary or deflationary pressures.

It was, as you may recognize, typical Bernanke arrogance. In plain language he was saying “don’t worry, the Fed will easily fix whatever damage might result from a bubble with the flick of its federal funds target wand.” For him, there is never an upper limit for central banking.

Greenspan, however, was more practical in his approach. He knew what it was that was always behind asset bubbles. It’s the same stuff that has worried central bankers from the very start:

Collapsing confidence is generally described as a bursting bubble, an event incontrovertibly evident only in retrospect. To anticipate a bubble about to burst requires the forecast of a plunge in the prices of assets previously set by the judgments of millions of investors, many of whom are highly knowledgeable about the prospects for the specific companies that make up our broad stock price indexes.

Who are we to argue with market prices? Well, history suggests there are times when we must.

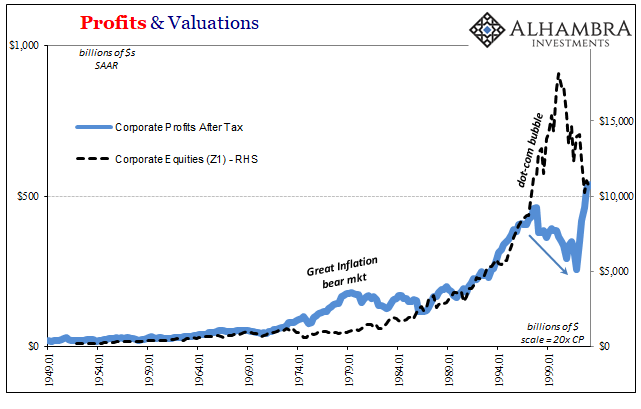

The issue isn’t really about confidence, rather it’s about what it is that so many people become confident about. Between the Asian flu low in early October 1998 and the 1999 Jackson Hole conference held at the end of that August, the NASDAQ rose 90%. From October 1999 to March 2000, it rose by another 85%. The former took about eleven months to achieve, the latter a mere five.

In hindsight, it was clearly a blow-off top. There were many reasons for it, of course, as nothing is ever so simple, but in a lot of ways they all traced back to a similar idea. The no-profit startups represented in the NASDAQ were given value based on, as Greenspan said earlier in his presentation, discounted future cash flows. They had negative cash flows at the time, so everyone believed that positive value was derived more exclusively by what was sure to come further in the future.

There was even by 1999 little evidence to support the idea. In fact, as far as earnings were concerned, there wasn’t any. Instead, it seems, people got the idea that the “new economy” was close at hand simply because it had been so long to that point without its appearance. Time worked in the bubble’s favor, which seems counterintuitive.

If something doesn’t happen for a long enough period of time, it would be rational to conclude that it is has become more likely that isn’t going to. In the stock market, indeed all history’s asset bubbles, the common element is that the premise is always fixed, and therefore it gets amplified in the course of time. What I mean by that is people really believed the “new economy” of the computer/internet/telecom revolution just had to pay off, big time. There was no wiggle room on that assumption.

The longer it went on without the payoff, indeed the more contrary evidence started to build up against it, the more (not less) certain people became that it was even closer to reality. If you believe wholeheartedly (emotionally) that it shouldn’t take more than five years for what you expect to occur, and it gets to the start of Year 5 without it having occurred, in this perverse sense you become even more confident that it’s right there in front of you (this thing is about to take off!!). Not only do you hold your bets that you made in the past, you might even add significantly to them at just insane valuations. After all, the thing survived through Year 4, so there is no way it could fail now.

Asset bubbles are inefficient markets and in one sense these modern versions have turned the premise of efficient markets on its ear. As large and as deep as markets have become, they have also exhibited a startling tendency toward this kind of herding. And it’s no wonder, starting with the “maestro” himself.

What was, after all, the Greenspan put? It wasn’t ever a real thing (dot-com bust and 2008 panic proved that conclusively), but it did reveal what was in the context of asset bubbles an irrational commonality. In other words, efficient markets as Greenspan described them in Wyoming in 1999 are predicated on millions upon millions of people reacting very differently to diverse and even conflicting data, and then bringing market prices to reflect a very broad consensus decision.

What if, instead, a huge proportion of the market all starts believing in the same myth at the same time? And it didn’t have to be the Greenspan put, either. In a very important way, that was the least of it. By the late nineties in particular, economic forecasting had become more and more centralized. What was going on in the economy was described by the Federal Reserve first and foremost (how did markets react to the Chairman’s optimism, or really perceived optimism at any given event?). If stock investors were extremely confident about the “new economy” and all its massive benefits, where might they all have gotten that idea?

Thus, if people were so sure the awesome potential was a real thing and that it had a chalk probability of lasting, the idea if it didn’t come directly from the Economists it was at least given an official seal of approval that at that time carried far more weight than was really rational.

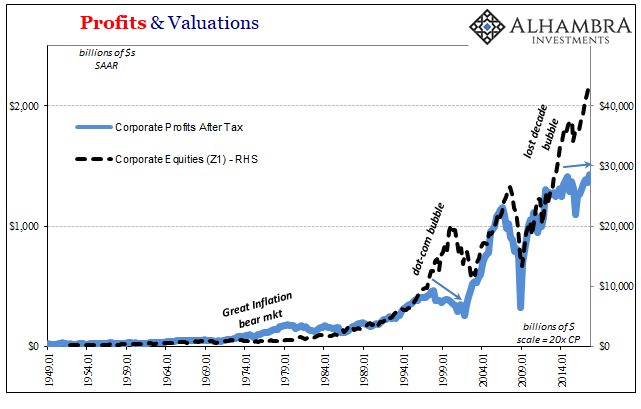

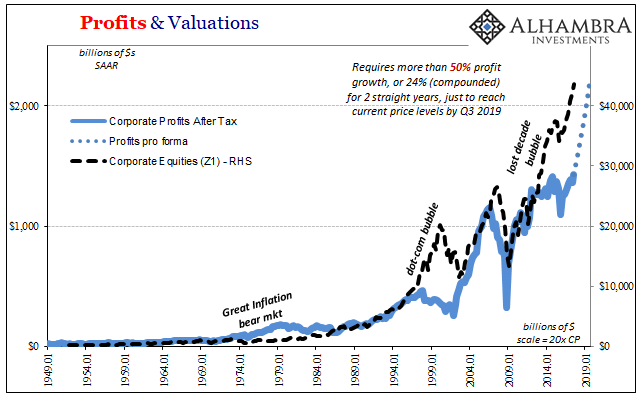

Just like the dot-com’s “new economy”, this current “boom” or “globally synchronized growth” doesn’t actually exist right now; it’s for tomorrow and people are absolutely certain that has to be the case in full part because Economists keep claiming with 100% certainty that very thing. Starting with central bankers, the characterization of every economic situation filters downhill from there. The economic malaise has gone on so long that there is zero chance it can go any longer, right? There is a pervasive top-down belief that the aftereffects of the Great “Recession” can only last until Year 10 (for instance), at most, and here we are starting Year 10. The big payoff must be tomorrow, or the next day.

I can’t help but wonder if we aren’t just repeating the same process, only replacing “new economy” with “minimally functioning economy” this time around. It sure looks like a blow-off top to my eye, but as Keynes once said, paraphrasing, your clients will literally kill you before you find out for sure. As noted yesterday, though, at some point the boom will have to boom. But what if it doesn’t?

Stay In Touch