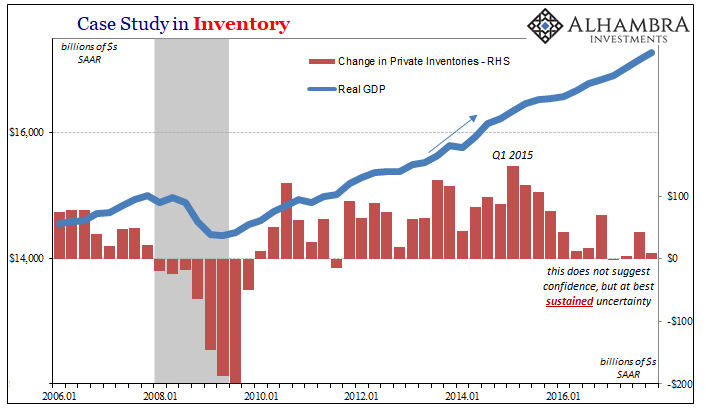

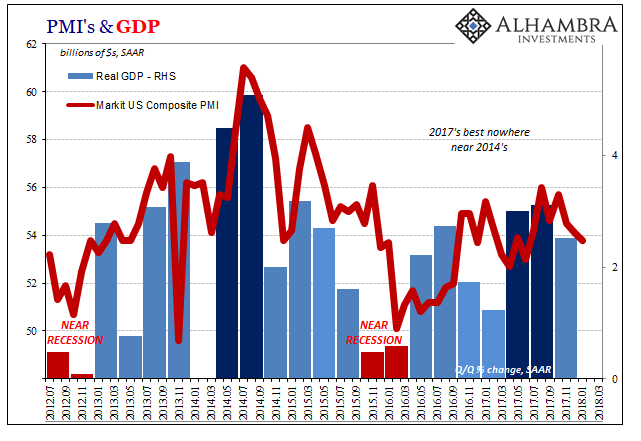

For GDP, one big piece that’s missing, or what’s kept it at a lower rate than in the comparable 2014 period, is inventory. Three and four years ago, American businesses couldn’t get enough. They piled into it at a record pace. The reason they did was almost surely Janet Yellen, or at the very least the mainstream economic projections that start always with the Fed’s upward biased models.

The BEA estimates that in the four quarters after the “rising dollar” began (Q3 2014 to Q2 2015), US firms took in around $400 billion of additional inventory. In dollar terms, it was by far the most in history; in percentages (of GDP) it was the largest inventory splurge since the late nineties. As an investment in the future, which is what inventory really is, it was on par with what the BLS was figuring in the jobs market.

Overall economic growth never really picked up all that much. The inventory was in anticipation of it doing so by 2015 at the latest. The unemployment rate suggested that even if the economy was still in low gear in 2014, there had to be a kick into high gear just around the corner.

Since that time, American businesses have been stuck in a sort of inventory limbo. A traditional recession always comes with an inventory liquidation; the desperate shedding of stockpiles of unsold goods as the approach of economic danger turns more immediate. The lack of liquidation, ironically enough, is what kept the 2015-16 downturn from becoming a full-blown cycle trough (a few quarters of negative GDP strung out over time).

Unlike in the past, there seems to be confusion manifesting as reluctance. If there was no inventory liquidation, there hasn’t been any restocking, either. That’s part of the difference lowering economic growth rates in 2017 versus 2014.

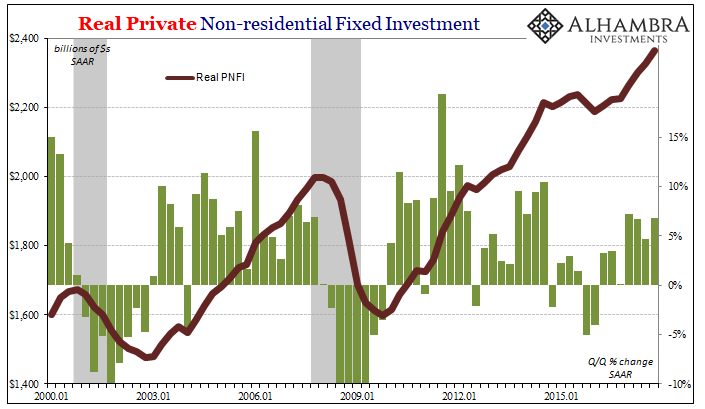

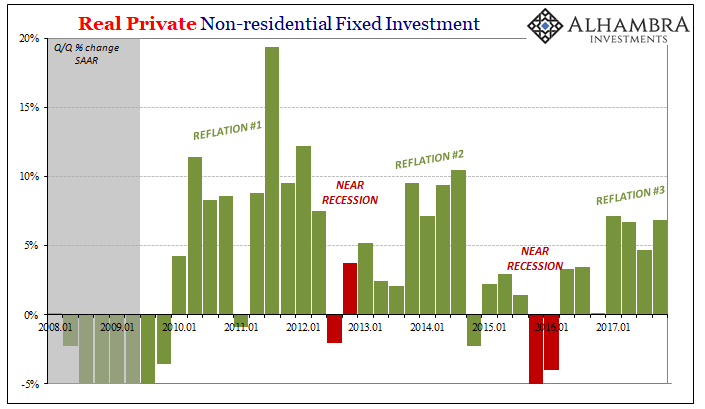

It’s not just inventory where this curious disinclination shows up. Other forms of business investment have been just as restrained. The most beneficial and basic of them is pure capex, the sort of productive investment any economy relies upon for baseline growth potential.

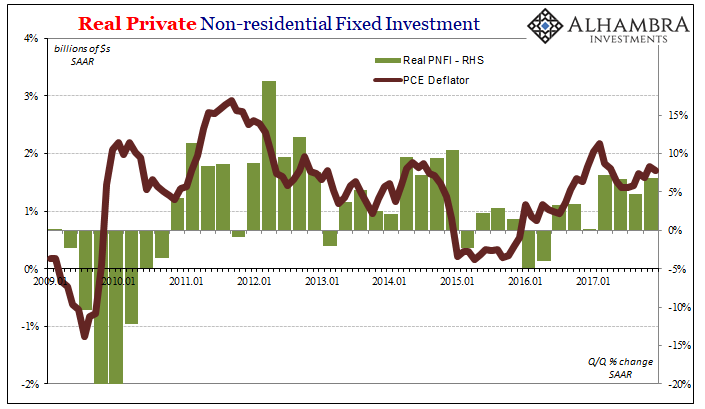

In GDP accounting, capex is Private Non-residential Fixed Investment (PNFI). The pattern over the last ten years is an all-too-familiar one, coinciding perfectly with the mini-cycles of upturns and downturns along the way during this “recovery.”

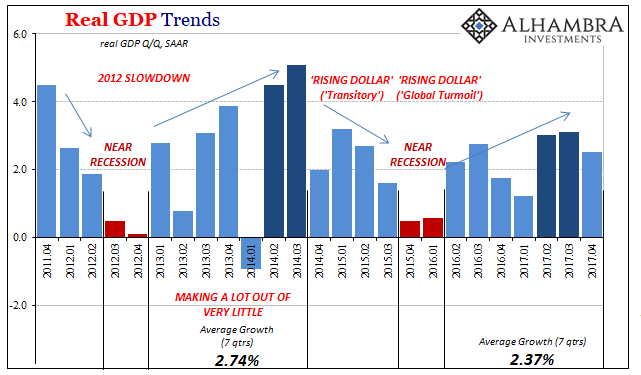

What stands out the most is, again, lack of confidence in business. Like inventory, firms did not add to productive capacity last year like with the same intensity as 2014. The “reflation” peaks keep getting smaller, meaning slower with lowered momentum.

The question is why. I don’t believe it’s a particularly difficult one to answer, especially given how the economic trends all played out since 2014. Janet Yellen was spinning the wrong narrative, and though there wasn’t a full recession in 2015-16 it was enough of a difference that domestic businesses had no choice but to pay close attention to that divide.

The economy may have moved again in later 2016 to another upturn, or “reflation”, but in business investment firms just aren’t buying it.

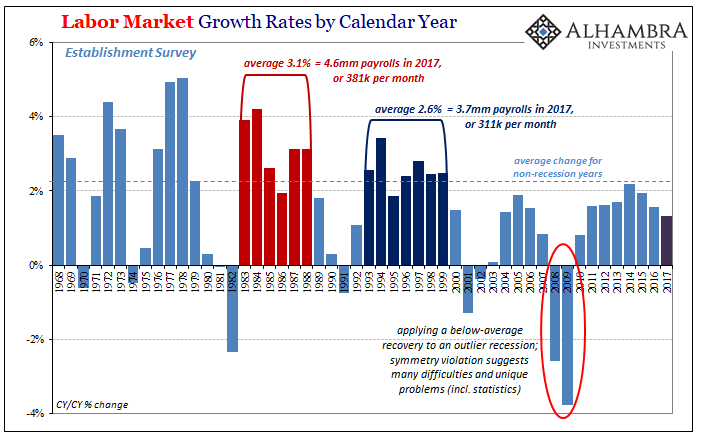

Very much like China’s version of capex, FAI, if there was just over the horizon “globally synchronized growth” it would be showing up right here. Businesses invest in inventory, capex, and especially labor based on their perceptions of the future. In all three of those cases, American firms (joined by others around the world) are obviously choosing to refrain from doing a lot more (hiring, in particular), and it makes all the difference over enough time.

In that constraint is the whole of mischaracterizing the current circumstances. Some call this a boom. Business investment shows that it is once again a false one, or at best prominently hollow. As growth appears set to slow again, suggesting that even the low peak of 2017 might have been the best of this mini cycle, it may have been wise on the part of US companies to approach the narrative with noticeably more caution this time.

Stay In Touch