If there is a boom here, I just don’t see it. Perhaps the term itself needs to be clearly defined. The common definition is a broad-based and sustained expansion, one that is beneficial to a wide cross-section of any society experiencing it. Since this is still nominally a capitalist system, eroded as it may be in some parts, “broad” would have to include labor into the mix.

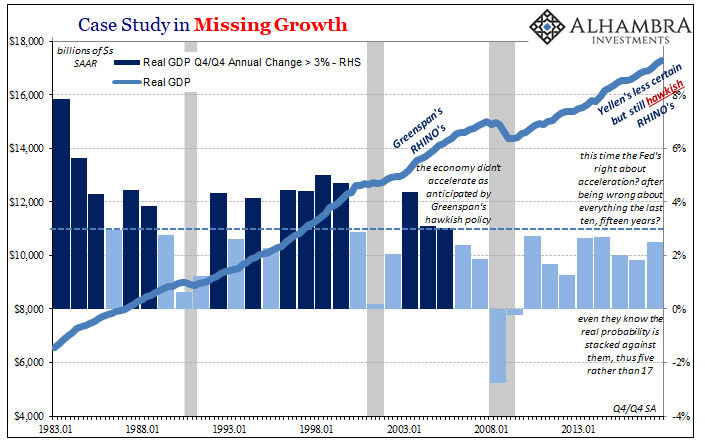

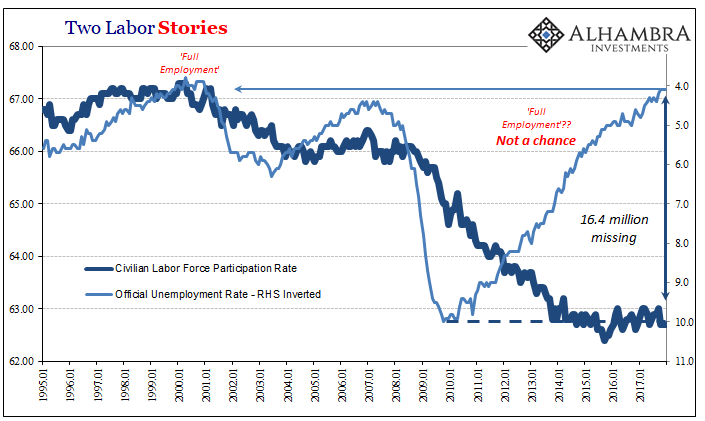

The unemployment rate has dropped to 4.1% according to the BLS, a number ready to be updated tomorrow with perhaps a three leading it. And yet, no matter how low it goes there isn’t any sign of inflation, wage-driven or otherwise. As noted yesterday, the FOMC even as it gets more (chicken) hawkish still has to talk about inflation always in the future tense depending as they do (given no alternative) on that one number.

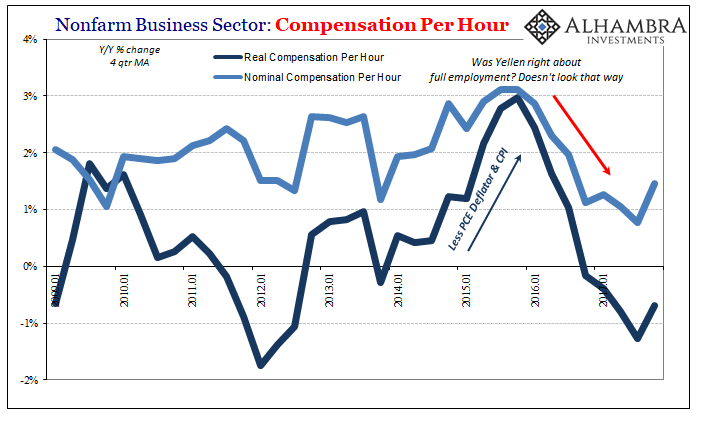

In some of the other BLS statistics (including the Establishment Survey) we can see why. The government agency released today estimates for hourly compensation among private domestic workers. They still are not good, and do nothing to suggest wages are being pressured by “full employment”, and more than that there can’t be anything like a boom underway. Or one indicated in the near future.

Nominal hourly compensation, which is where inflation would show up, rose by all of 1.8% quarter-over-quarter (annual rate). The 4-quarter average moved up to 2.4%, but only because the negative nominal “growth” from Q4 2016, the quarter at the center of “reflation”, dropped out of the moving average.

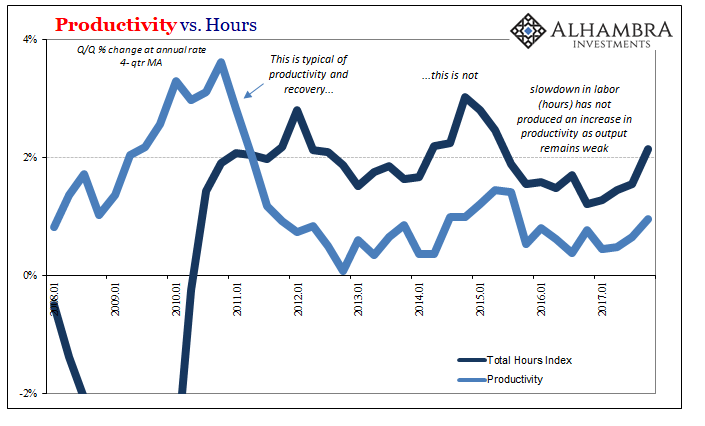

In real terms, American hourly compensation has been falling since “reflation.” That’s about as negative a reflection on economic fundamentals as there could possibly be. And it’s traced directly to continued economic weakness, now manifested quite rationally in a persistently slowing labor market. Even though payroll growth has declined, it still hasn’t triggered a productivity gain, which is why it keeps on slowing.

The other side of labor expansion is obviously business profitability, or in the parlance of the BLS figures and those the BEA prepares in conjunction, productivity. The more output stays in this weakened configuration, the less businesses will be willing to do with regard to utilizing the labor force – both what is already employed and what would otherwise be out of potential slack. This is basic economics, intuitive stuff that doesn’t require complex regressions (R*, among many) to verify.

Productivity has been stuck for a very long time now at near-zero. It forms a trap of sorts, or what seems to be a chicken and egg problem, where weak output growth keeps labor utilization low because of little or no productivity gains, which then suppresses output since workers are consumers.

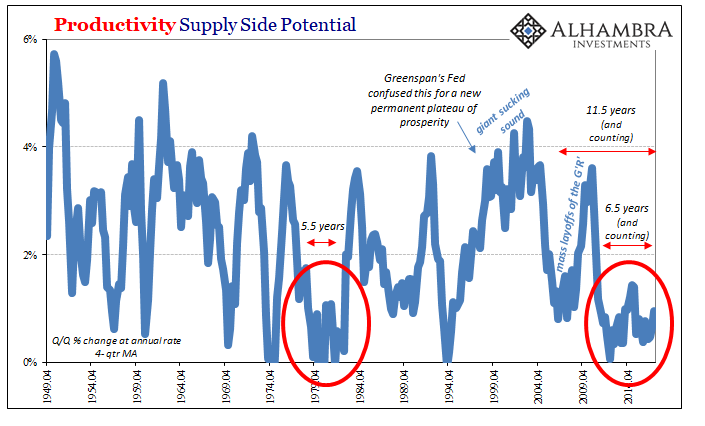

How serious is this? It’s nothing like we’ve seen before, at least not in the current set of statistics. It happened once in the 1930’s during the Great Depression. The closest we have come to this depressed state is the apex of the Great Inflation beginning in 1978. For 5 and a half years starting before and then during a double dip recession, US productivity was as bad it is now.

That says a lot about the fundamental economic circumstances we are dealing with, and why the very idea of a looming, inflationary economic boom is totally ridiculous. This economy remains as bad as it was during one of the worst periods of sustained economic malfunction in postwar history; and the compensation figures show that hasn’t changed, and isn’t about to no matter what the Fed does or why it claims it will.

One major clue as to why is in realizing that this low productivity state actually dates back further to 2006. The boost to productivity in 2009 was because of mass layoffs in the Great “Recession”, as is common for any recession. What was supposed to happen thereafter was a normal business cycle where more positive productivity growth from new investments gives the business cycle rebound more than enough room to re-utilize existing labor as well as slack.

Instead, output stayed weak year after year. What changed in 2006, before the “recession”, was the housing bubble – or, more specifically, the debt supplement to US incomes that had tailed off coincident to the “giant sucking sound” Ross Perot had warned about in the early nineties. Take away credit growth, and output could only be weakened thereafter. Take away the foundation for productive investment, and it appears like a trap.

Since the eurodollar system had led capex primarily overseas throughout the early 21st century, there wasn’t anything to drive productivity once the debt supplement disappeared (in the eurodollar reversal). Worse, from a more global perspective, this pattern has been replicated all over as productive investment has fallen off dramatically worldwide. The eurodollar system has screwed over everyone now, not just US workers in the new millennium.

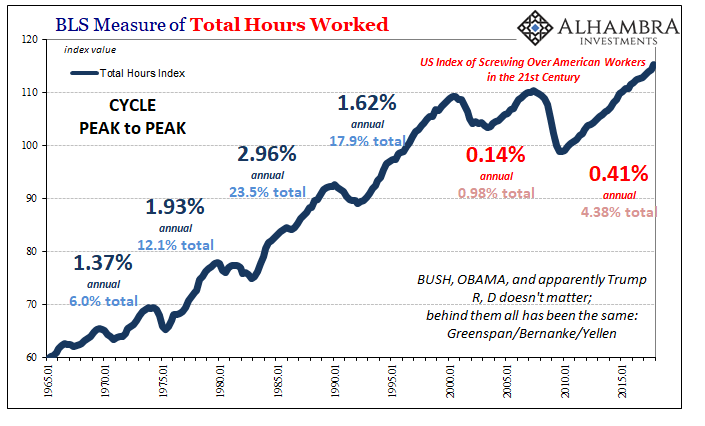

The BLS today figures that American labor in Q4 2017 put in only 6% more hours than they did in Q3 2000, despite sixteen years distance. This is an enormous difference, a clear shrinking of economic potential.

To get to instead a real boom, not one of the several imaginary ones we hear about intermittently the past decade, something big would have to change. Big. What has?

The compensation data as well as the numbers relating to productivity demonstrate that to the end of last year, despite all mainstream expectations entering 2017, nothing did. It didn’t matter what the unemployment rate was, the actual economic condition was nothing like what it appeared to suggest. So, we begin 2018 with all the same deficiencies, all the same questions none of which yet have any answers. Where’s the boom?

Stay In Touch