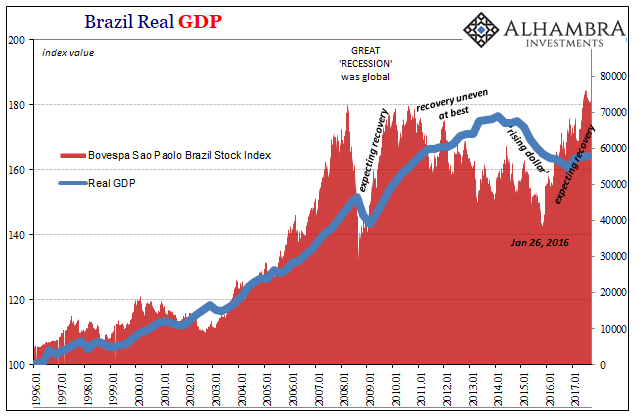

Brazilian stocks closed out January on an impressive run. Like stock markets all over the rest of the emerging market economies, Brazil’s has been on fire. The Sao Paolo Bovespa stock index had stumbled a bit in the middle of December, coinciding with a drop in the real against the dollar in that fit of global illiquidity, but between December 14 and the most recent peak on January 26, the index gained an impressive 13,102 points. That’s +18% in a little over a month.

Going back coincidentally to January 26, 2016, Brazilian stocks in the Bovespa have gained 128% in two years. That’s the kind of returns EM investors have been expecting and were once taken for granted.

Given the “wall of worry” even for riskier emerging market stocks, it would seem those returns anticipate complete recovery for more than Brazil. They are almost surely the fruits of “globally synchronized growth” that will benefit the BRICs above all others. A resurrection of the precrisis global model would seem appropriate, the impetus behind the rocket-like ascent going on in Sao Paolo.

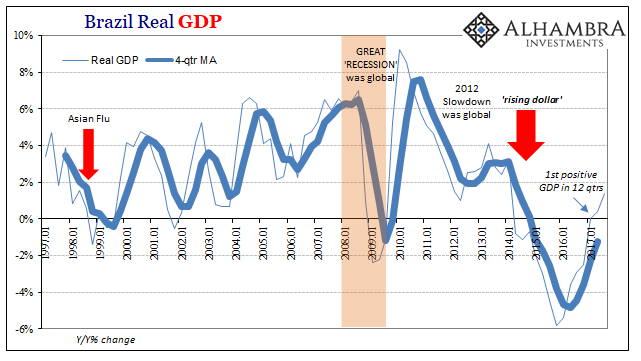

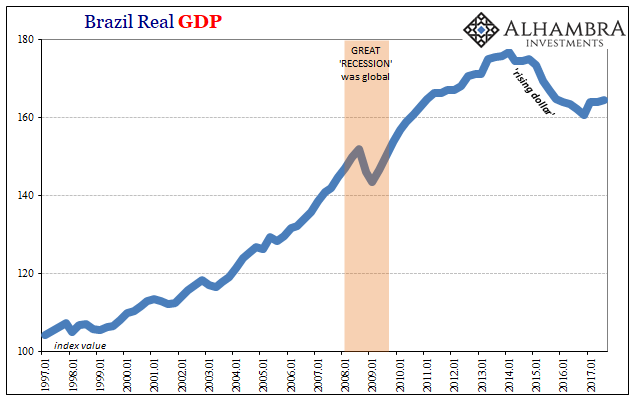

The economic statistics coming out of Brazil have been encouraging. Real GDP which had contracted for an astonishing twelve straight quarters is now positive for two in a row (through Q3 2017). In the third quarter of last year, GDP gained 1.4% year-over-year. Like you’ll hear about a lot of other statistics around the world, that’s the highest growth rate in more than three years.

It’s not that 1.4% is by itself the basis for surging stock prices, it’s the straight line upward the positive number supposedly represents. In the grand scheme of things, 1.4% is surely just the first stop on the way to 3.4%, 5.4%, and eventually 6.4% or 8.4% like the good ol’ days, right?

The mentality driving the Bovespa is the assumed probability that’s the correct interpretation. If Brazil is righting itself, better get in now before it actually happens lest one miss out. It’s a game of probability, and right now it’s hard to find anyone down on the Brazil and the EM’s.

That’s the case even as Brazil’s economy struggles to gain traction. Though encouraging, everything has to evaluated more than relatively. Things are moving in the right direction, of course, but that’s not necessarily the same as what stocks are pricing. The absence of further contraction does not immediately propose a change to robust growth.

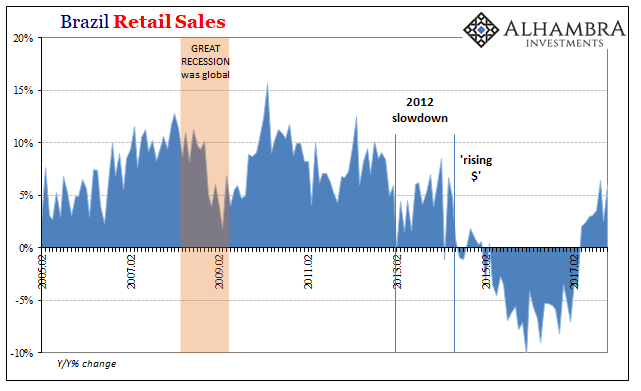

Up and down Brazil’s economic accounts, the pattern that emerges is a familiar one. Positive numbers are now uniformly evident, but they aren’t the same as they once were. Retail sales, for example, rose 6.4% year-over-year in September 2017, but that was just one month. It’s not quite the same robust expansion as when retail sales were regularly rising at 10% and more. And that rate doesn’t really begin to make up for the more than two years retail sales shrank.

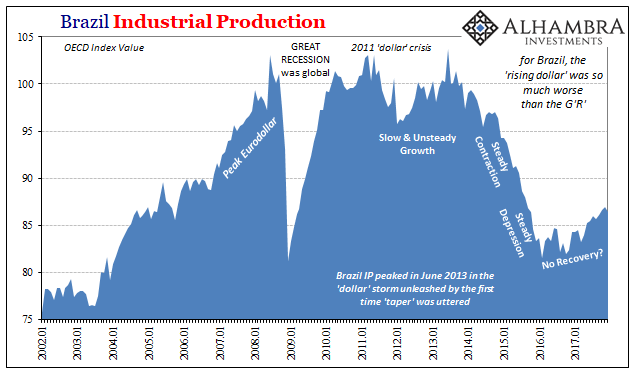

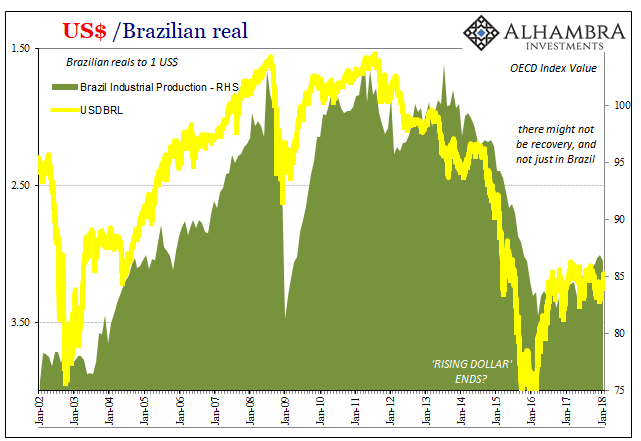

Nowhere is this absence of symmetry more conspicuous than Industrial Production. IP is the bedrock of the Brazilian economy, the resource production that for more than a decade shifted the country into a maturing economy. It built the modern Brazil.

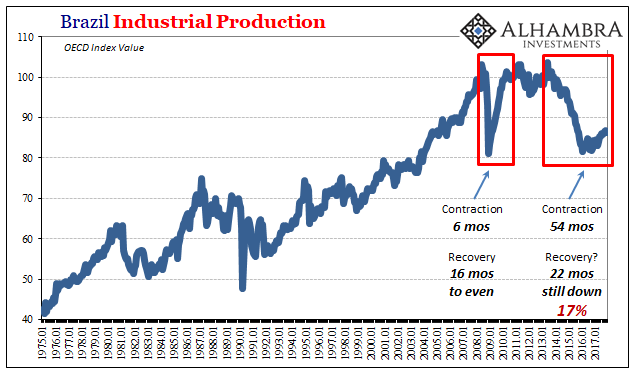

The Great “Recession” that finally hit South America in early 2009 was sharp, but ultimately short. IP declined for six months, falling then at a total loss equivalent to the latest economic crisis. It recovered that loss, however, in a mere 16 months.

This time, though Industrial Production fell for year after year, totaling now 54 months (through December 2017), the index is still down 17% from the 2013 peak. It’s been moving upward for the last twenty-two, but little actual progress has been made. There is no recovery, no symmetry.

It’s the same for GDP. Once you move away from the more recent quarterly positives, you see like IP Brazil’s GDP rather than moving toward rapid, robust recovery has instead started to linger more toward the bottom. It sets up an enormous, and enormously important, dichotomy. And it’s one that we’ve seen in Brazil, as elsewhere, before.

From November 2008 through early 2011, Brazilian stocks stormed higher in anticipation of full and quick recovery. Investors were betting that the EM growth model would remain intact despite the long and painful reach of the Great “Recession.” The “dollar” issues that started to bite harder by 2011 indicated the beginnings of what would eventually become the “rising dollar.”

For Brazil’s economy, that meant a period (Q3 2011 to Q2 2014) first of uneven growth that further raised suspicions about how the country might fare if the prior 2009-11 assumptions proved false. Stocks sank as those concerns were more and more proven correct. By 2014 and the full weight of the “rising dollar”, Brazilian stocks were already down quite severely and would drop even more through the worst of it.

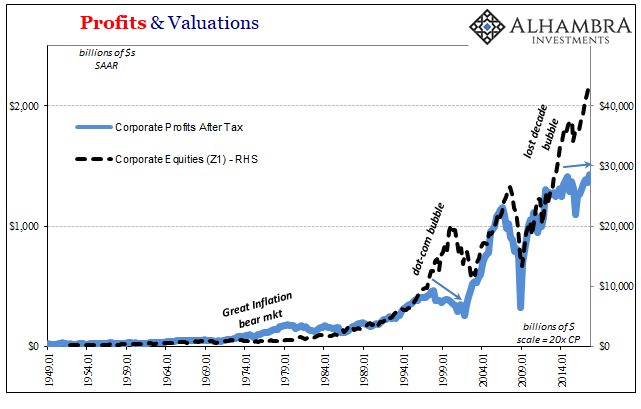

Now we are back in 2009-11 again, with stock prices surging on the winds of a recovery scenario that investors are convinced will be fulfilled given enough time. That’s really the issue here, meaning that the longer Brazil and the EM’s (the whole global economy) continues on in a low growth state, one that isn’t yet set back by another monetary disruption, the more convinced stock investors are that it has to be the case. The longer it takes for the scenario to begin, the more certain stock prices will further price out this best case.

The flipside is the one nobody wants to consider, though it is the more rational interpretation. The longer everything goes without a recovery, a true one, to emerge, the less likely it will. That’s how these things work – symmetry. In any cyclical case, what goes down comes back up immediately, just like Brazil and indeed the rest of the EM’s (including China) in 2009 and 2010. If it goes down and stays down, well…

There may be a lesson here for more than just stock values in this one South American country. If there proves in the end to have been a stock bubble it will have been based on this one assumption for which Brazil provides a good example. It may seem as elementary as two follows one, but the end of a contraction, even an amazingly deep one, doesn’t mean everything will start to go right.

We’ve seen several times in the recent past where stocks are priced very aggressively on predicted shifts in the growth baseline. It provides an answer to the question, how can stocks be up so sharply and the economy so bad at the same time? The answer is the presumed probability one or the other will end. Either stocks will stop being up so sharply, or the economy will stop being so bad. That’s ultimately why economic symmetry is so important. The boom has to boom at some point.

Stay In Touch