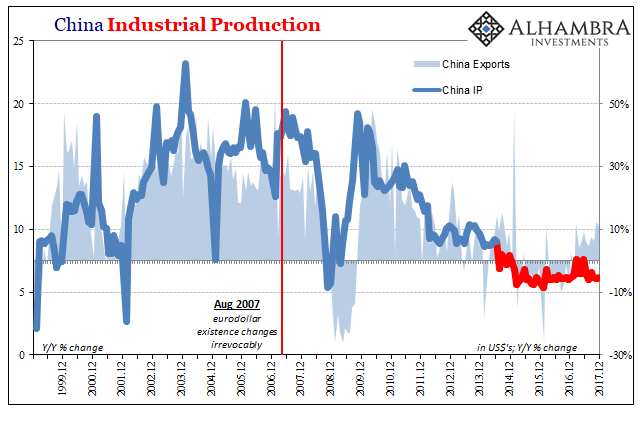

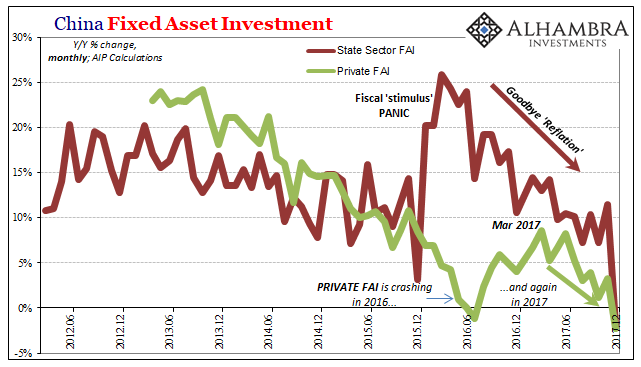

The conventional interpretation of “reflation” in the second half of 2016 was that it was simply the opening act, the first step in the long-awaiting global recovery. That is what reflation technically means as distinct from recovery; something falls off, and to get back on track first there has to be acceleration to make up that lost difference.

There was, to me anyway, a lot of Japan in it, even still if “globally synchronized growth” was to prove anything more than a marketing pitch or bumper sticker slogan it was always going to speak Chinese. Economic gravity being what it is, without China’s vast input into the anticipated healing process there just couldn’t be anything more than we’ve seen previously (2014).

As reflations tend to go, they start first with markets and market prices. In economic terms it’s quite simple: commodities. If the world needs to use more of them because everything is getting so much better, they will rise and rise sharply before it ever happens. And if reflation is true to the term, they will keep on going so as to at least get back to where they were before, if not surpass prior highs.

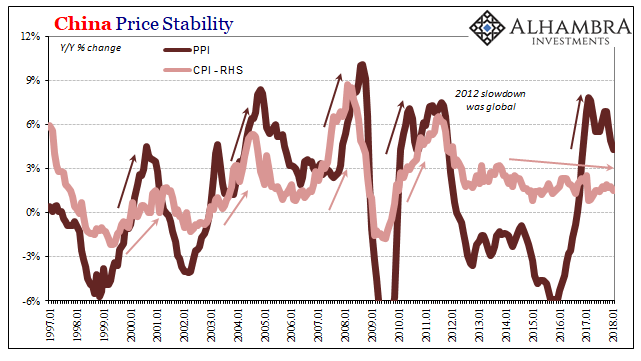

The second half of 2016 passed the first burden; commodity prices rose sharply which fed into the worldwide inflation story that we know very well in 2018. In China, it was reflected almost immediately by producer prices.

The Chinese PPI had contracted for 53 straight months. Going all the way back to April 2012 and the 2012 slowdown, that deflationary trend mirrored everything that was wrong with the global economy that Economists had either ignored or didn’t know existed.

For September 2016, the PPI for the first time in almost five years turned positive. It was, seemingly, an important turning point and was widely interpreted in that fashion. Psychology of markets and economy tends to place a great deal of importance, too much, on round or even numbers, and always a change of sign. People think in linear, straight line terms.

By January 2017, producer prices were rising at nearly a 7% rate. For many, that confirmed reflation as an almost completed first step toward recovery. And in China, no less.

Chinese inflationary pressures went up a cog in January, led by another enormous surge in producer price inflation (PPI)…

A hot reading, and largely reflective of higher input costs as a result of booming commodity prices…

And with factory gate prices on the rise, there’s signs that those upstream price pressures are now being passed on to consumers.

It’s that last part that is important. Not that we want rising consumer prices, but the incidence of accelerating CPI’s (or HICP’s) confirms any suspicions that an economy is healthy enough to absorb price pressures. If businesses see rising input costs but are reticent to raise their own end prices to offset them, something significant continues to be wrong.

It would suggest the commodity “boom” was anticipating recovery that just wasn’t there. Market prices are always looking forward, but that doesn’t mean they are always pricing the “correct” scenario. Nothing goes in a straight line, so it may take time for even commodity investors/speculators to figure out what’s real, and what was just something someone printed on a bumper sticker or an IMF report.

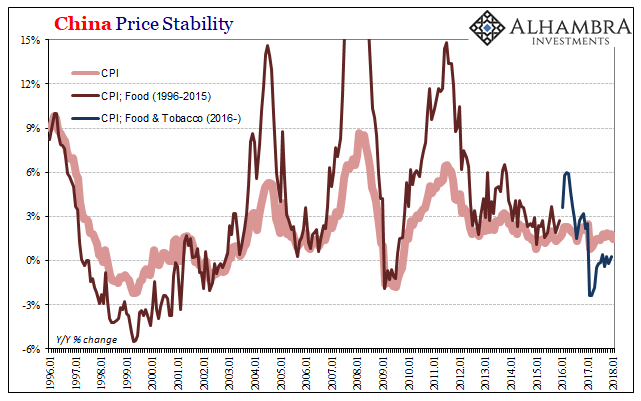

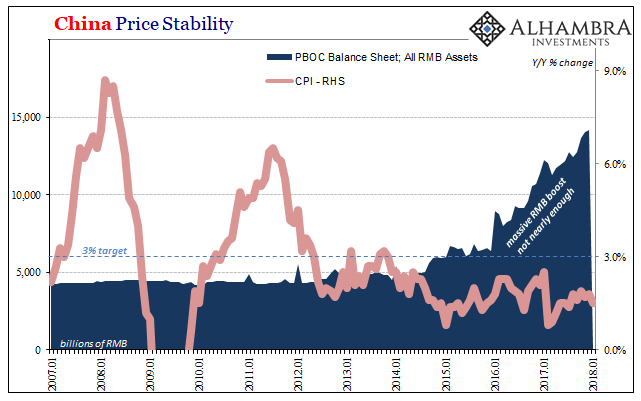

Despite rising producer prices in early 2017, it never did flow to China’s CPI. It was a curious omission because in the past there had always been a very clear correlation; in the past China’s “miracle” economy would take commodity price pressures in stride, even if that meant a surging CPI now and again.

The difference in late 2016/early 2017 was obvious; “something” had changed whereby commodity prices were “booming” and suggesting expectations for a more positive outcome last year, but no follow through in consumer prices despite well-documented pig-related food inflation concurrent to it.

The more 2017 passed into history, the more it became clear that commodities were, to borrow a phrase from the Winter Olympics, a little over their skis. China’s consumer prices haven’t budged one bit, remaining substantially below the government’s explicit 3% definition of price stability. Overall, there has been no economic account that would confirm any sort of broadly based acceleration, either.

This despite a massive monetary program designed in RMB to offset continuous, chronic “dollar” erosion. If inflation is a monetary phenomenon, and it is, then China’s inflation trends tell us a lot about the failure of “globally synchronized growth” to be anything more than the latest recovery fantasy (the third since 2009; the fourth if you count, as I do, the middle of 2008, too).

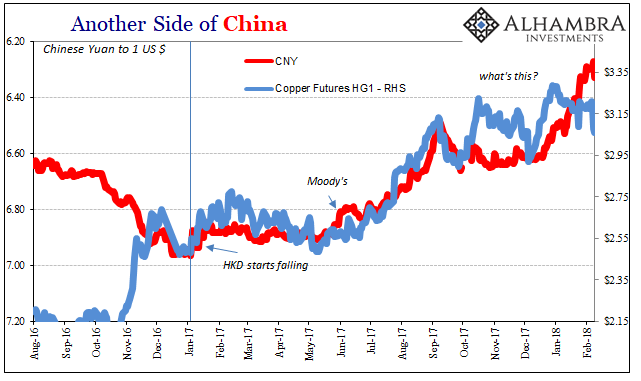

China’s CPI decelerated again in January 2018, the growth rate falling back to 1.5% or half the level it is supposed to be gaining. The PBOC hasn’t met its inflation target since November 2013 – right about when CNY started to fall, or, to put it the other way, the “dollar” started to rise. Instead of reflation, this data corroborates instead the worst case of the eurodollar curse. It knocks an economy down, and then the economy never gets back up. Everyone expects it too, of course, because that’s what all prior economic history had shown.

In case anyone hasn’t noticed, the last decade is different; particularly the last half decade, really different.

At 4.3% in January, the Chinese PPI is the lowest since November 2016. For reflation to become recovery, or even to stay at reflation, there has to be sustained momentum and for much more than just commodities.

Stay In Touch