This is the Year of the Dog, or it will be starting tomorrow across Asia. Tonight marks the opening of celebrations for China’s Spring Festival Golden Week. These weeklong breaks in Chinese contributions to the global system have over the past few years rarely been so uneventful. Their absence has been noted both good and bad; the very worst of the global liquidations ending on February 11, 2016, for example, took place while that country was on holiday.

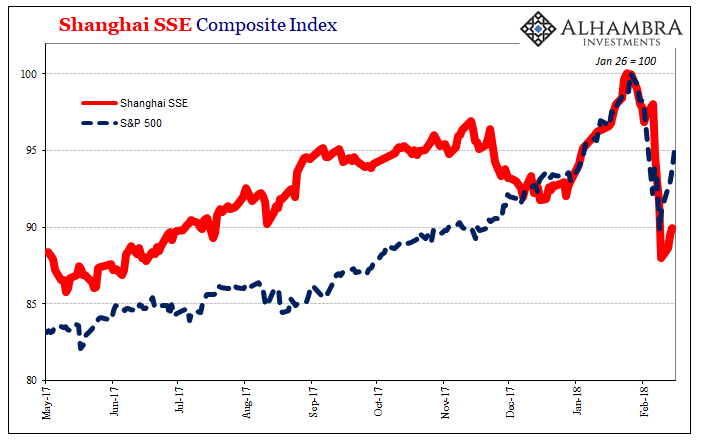

With the Shanghai stock exchange closed starting today for Lunar New Year’s Eve, its composite stock price index will have to remain much closer to the bottom of the recent selloff. In fact, after collapsing by a little over 12% in just a few days, a clear sign of liquidation, the index has retraced only 2% from its trough.

That compares with the S&P 500 which fell top to bottom almost exactly 10%, and has since gained more than half of it back.

That might propose relatively more apprehension, uncertainty, and, yes, illiquidity in Asian markets as compared to those in North America or Europe. This isn’t really surprising given what’s gone on over there.

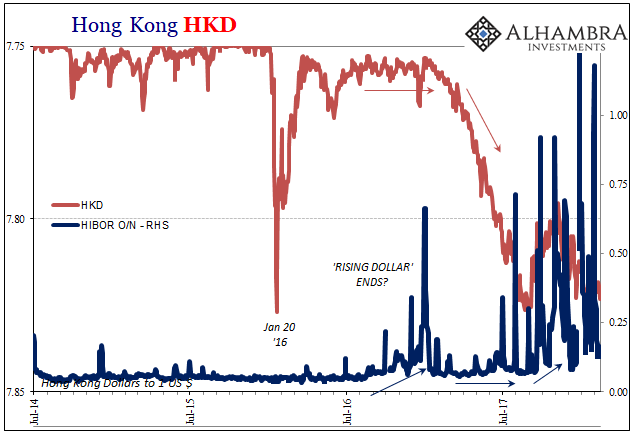

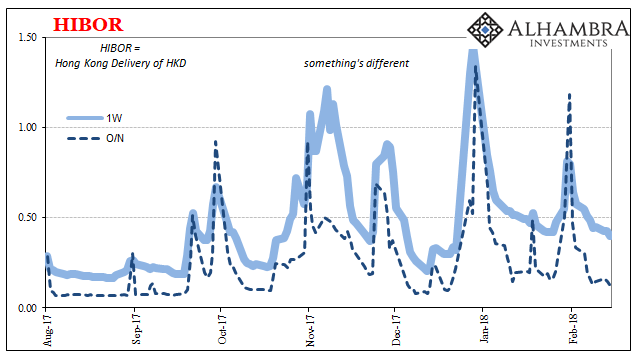

Incidentally, the dramatic slide in stocks globally started on January 29 – as Hong Kong money rates surged into what has become a regular month-end problem. There was never anything like this before in HKD or HIBOR, and it didn’t happen last January, but Hong Kong banks and the city’s monetary authority have been visited by extreme volatility and, yes, illiquidity.

We know why. The issues in Hong Kong are not strictly isolated in Hong Kong. As a money center and redistribution point for global funding, its banks occupy a special position in the eurodollar framework not dissimilar to that still held by Japanese banks. Over the past year, these Hong Kong firms (which may be foreign bank subs domiciled there) have gained in importance, of course, given what they have been tasked with vis a vis China.

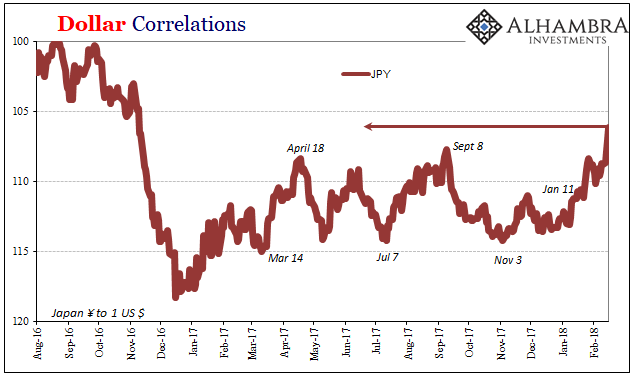

While Japan has therefore been downgraded of sorts in the pecking order of marginal eurodollar rank, that doesn’t mean Tokyo is any less of a meaningful place for global “dollar” liquidity settings. Thus, we have to take note of this:

The rising yen is an indication of rising liquidity risk. The real carry trade has always been Japanese banks loaded up with low, zero, or now negative yielding bank reserve balances. To make productive use out of them, and to make further mockery of QE’s 1 thru 9, as well as QQE 1 & 2, yen liabilities were easily and fluidly swapped into dollar liabilities before 2015, with Japanese banks paying whatever small(ish) premium so as to profit on structural dollar deficiencies in places like China.

Since the “rising dollar”, that had only put strain on this “carry trade” where the direction of the yen against the dollar signified the relative willingness, or unwillingness, of Japanese banks to redistribute “dollars” as Hong Kong banks do now.

It’s far too early for solid conclusions about the yen, but it does match what we see across many Asian markets including those in both Hong Kong and China – especially this latest upward leg in JPY that began as US$ repo fails spiked in January, the week before the global liquidations hit.

Though it works out as the dollar falling against JPY, Asia doesn’t appear to be buying, at least not yet, the restored falling dollar that the rest of the world has bought this week. It will, as usual, be interesting to see what happens when China comes back from its celebrations over the start of the Year of the Dog.

Stay In Touch