We have ample enough evidence for the efficacy, or inefficacy really, of tax cuts as fiscal stimulus. They have been deployed numerous times all over the world the last ten years, and the results have been nearly identical in all. Most charitably, proponents have been left with some form of “jobs saved” to describe, counterfactually, how if they had not been undertaken things would have been worse. That’s not stimulus, it’s distraction.

The same goes for fiscal spending, particularly based on raised budget deficits which in the Economics textbook is Chapter 1 on dealing with the business cycle.

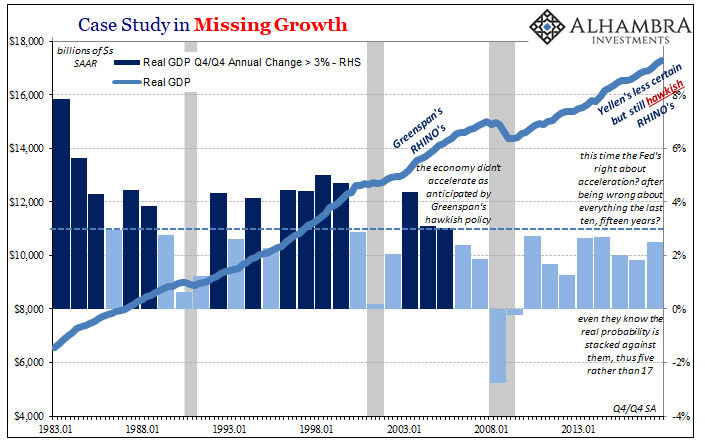

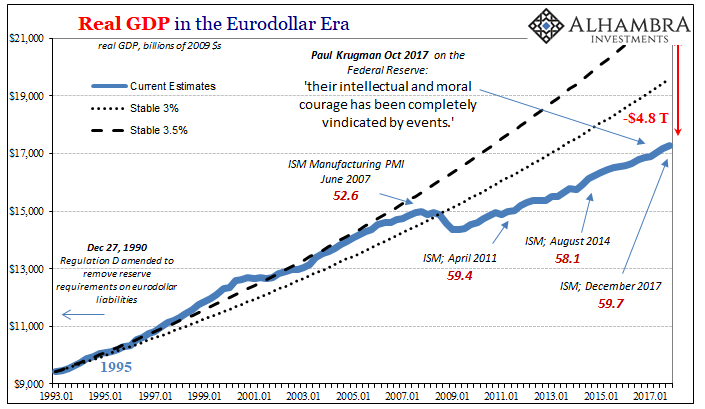

The current inflationary boom narrative therefore rests in large part on what’s different this time as compared to those previous (the remaining balance of the idea is attributed to the Fed’s fingers crossed strategy that amounts to faith in just random good luck plus time). President Trump’s corporate tax reform enacted just before yearend last year has left inside it a lot if not all of these residual hopes.

Not only was the corporate tax rate reduced substantially, contained within it was a one-time tax holiday for firms interested in repatriating “stranded” foreign income. The intent is straightforward and even intuitive – the return of funds (already vested in dollar assets if in accounts domiciled abroad) is meant to spur capex as well as wages. We’ve heard quite a bit about the latter, though in anecdotes rather than data (and in the form of, so far, one-time bonuses to employees, not broad-based and permanent advances in pay, not that bonuses are in any way a bad thing).

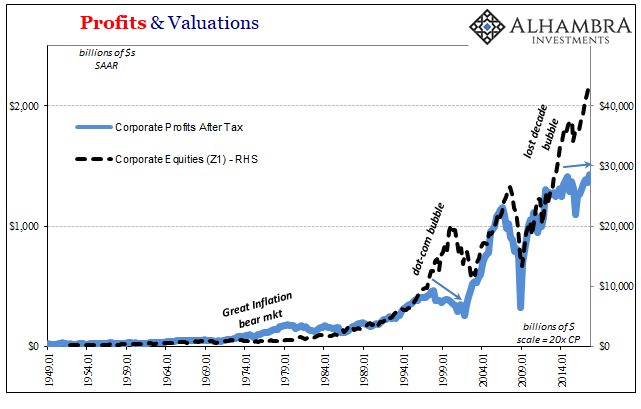

In terms of economic analysis, if there is to be any lasting positive contribution from tax reform, it must follow through productive investment. It’s the one glaring omission from this economy, detached from the intended and expected “recovery” by liquidity preferences. From the view of the corporate boardroom, it is far less of a risk to invest in one’s shares than one’s real economy facilities. The reason is equally simple; the stock market goes up, the economy does not.

Does a rebalancing of cash flow restrictions change that?

Past behavior suggests that it doesn’t, won’t, and didn’t before. Like the Bush tax cuts (really a helicopter) of early 2008, no one remembers the “tax holiday” of 2004 because it was just as effective, meaning ineffective.

In 2003, the recovery after the especially mild dot-com recession dragged on into what had become a politically dangerous “jobless recovery” as the Democrats in opposition had taken to calling it (correctly, at least in part). Even though that business cycle trough had ended all the way back in late 2001, the Fed didn’t get down to 1% for federal funds until June 2003, and the fiscal side of the government debated all kinds of ways they might push the economy to a better level before the 2004 Presidential Election (George W. Bush uniquely wary of “it’s the economy stupid” given what had happened to his father’s re-election chances in 1992).

Among their textbook solutions was a corporate tax holiday. The rate for the repatriation of foreign earnings would be slashed from 35% to just 5.25%, producing, Economists said, a huge boost to the supply side through increased capex and the jobs that beneficially follow it.

The Bush Administration was warned, repeatedly, that wasn’t going to happen. They did it anyway because Economists are afforded a level of influence that just doesn’t befit their actual contributions (see: 2008, and everything after). When the Obama Administration in 2011 sought out a similar idea for the same reasons (a “recovery” one year before a Presidential Election that wasn’t living up to anyone’s expectations), the Treasury Department wrote of using another foreign earnings tax holiday:

In 2004, when the U.S. enacted a repatriation tax holiday, the goal was to encourage U.S. multinationals to pay bigger cash dividends from their overseas subsidiaries and use the cash to make investments in the United States. Unfortunately, there is no evidence that it increased U.S. investment or jobs, and it cost taxpayers billions.

Although advocates argue that a repatriation holiday could be costless or even raise tax revenue, the official Congressional scorekeeper, the Joint Committee on Taxation, estimated before enactment that the 2004 repatriation holiday would actually cost billions of dollars.

The JCT studied the 2004 holiday and found (as the Wall Street Journal reported in October 2011):

The 15 companies that benefited the most from a 2004 tax break for the return of their overseas profits cut more than 20,000 net jobs and decreased the pace of their research spending, according to report from the Democratic staff of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations released Monday night.

That report, produced by the partisan majority staff of the Senate Subcommittee, it should be pointed out, had quite a lot more to say on the issue of stock repurchases or buybacks, as well as executive compensation.

Despite a prohibition on using repatriated funds for stock repurchases, the top 15 repatriating corporations accelerated their spending on stock buybacks after repatriation, increasing them 16% from 2004 to 2005, and 38% from 2005 to 2006, while a broad-based study of all 840 repatriating corporations estimated that each extra dollar of repatriated cash was associated with an increase of between 60 and 92 cents in payouts to shareholders.

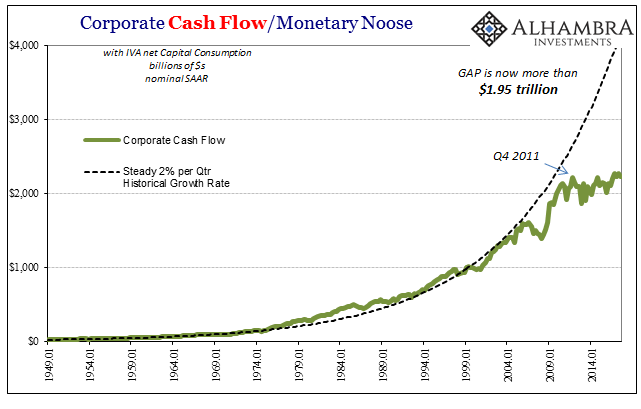

This was, in fact, the basis for the Obama Administration’s repeated rejection of another corporate tax holiday despite a clear need for, and discussion of, constant stimulus. There is no evidence that businesses are constrained by cash flow, and that any constraint is a product of the topline lack of revenue (meaning economic) growth. They were in 2008, and that restraint caused an apparently permanent change in their behavior, a caution and attention to costs and liquidity we’ve not seen since the 1930’s.

What’s missing is the other side, meaning economic opportunity. Rearranging the accounting of taxation and profit geography doesn’t change the nature of the shortfall. In theory, if the corporate tax holiday did work as advertised, we might expect some increase in real economy benefits, though their magnitude would still be up for debate.

Instead, as the Financial Times notes:

Flush with cash after the Republican tax cuts, Cisco announced on Wednesday that it was building gleaming factories across the US, employing hundreds of thousands of workers to make the latest cutting-edge routers.

Sorry, of course not. The money is going back to shareholders.

Indeed. Announced stock buybacks are up to record levels already in 2018, surprising perhaps only Economists who can’t seem to read anything other than what’s printed inside their textbooks. It’s one reason, the main reason, why stock prices can be so divorced from the real economy. As an expression of liquidity preferences derived from lack of economic opportunity, corporations buy more stock at the top than at the bottom.

It’s not value, it’s upside down. A tax holiday even expressly against this kind of activity will encourage more of what’s wrong, not start a trend toward what’s badly needed.

The longer it goes, meaning lack of economic growth, the harder it becomes to change the negative patterns that become established in response. Those expecting corporate tax reform, specifically the foreign profit holiday, to have done some good on that account are likely to be yet again disappointed. There may be merit to reforming corporate taxation and taxation in general, but that is not our consideration here in terms of evaluating potential economic effects.

Rather than suggest “what has changed?” as a meaningful answer to getting out of one lost decade starting well into a second, the latest tax reform may actually be more in the “what hasn’t changed” column further tightening the noose of all which continues to be wrong.

Stay In Touch