Warren Buffett is complicated guy. He’s made out to be like your grandfather, the kind old guy who gives you simple and effective investment advice to help you make your way in this complex world. His idea for never investing in a business you don’t understand is good advice. It’s just that he doesn’t actually practice it.

Any substantial review of Wall Street history shows Warren Buffett at the center of a whole lot of complex issues. Not only was he piling $5 billion into Goldman Sachs, of all names, the week after Lehman failed (with Goldman at the same time petitioning the Federal Reserve to become a “bank”), it was Buffett who fifteen years before showed up at the center of one of the more noteworthy (and misunderstood) events of modern monetary evolution.

I wrote a few years ago:

I have no particular issue with Buffett making those investments, only the pretense of intentional mysticism that surrounds them. The reason the criticism of crony-capitalism sticks is because this was not Buffet’s first intervention to “save” a famed institution on Wall Street. If Buffet’s convention is to stick with “things you know” then he has been right there through the whole of the full-scale wholesale/eurodollar revolution.

Buffett’s track record in buying stocks and firms is unmatched, and unassailable. The man knows his stuff. It’s the myth and legend that is more than a little overdone, and therefore unhelpful.

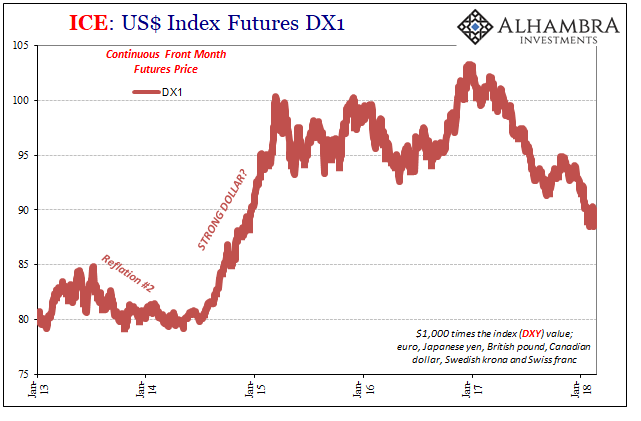

In March 2011, the head of Berkshire Hathaway told an audience in New Delhi, India, that he would avoid at all costs all longer dated bonds. The issue, in his view, was inflation, or, more specifically, the destruction of the US dollar that so much money printing (QE) was at some point going to unleash.

I would recommend against buying long-term fixed-dollar investments. If you ask me if the U.S. dollar is going to hold its purchasing power fully at the level of 2011, 5 years, 10 years or 20 years from now, I would tell you it will not.

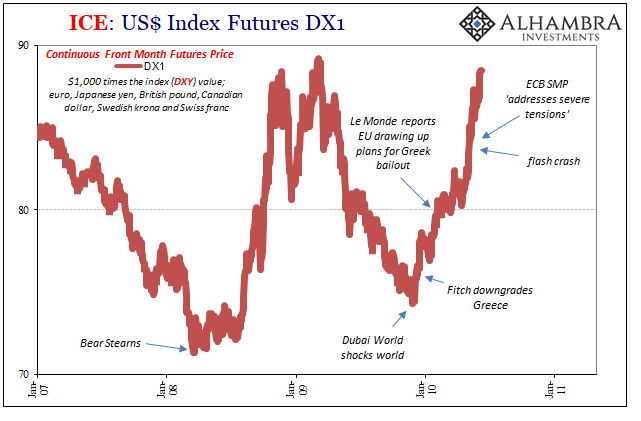

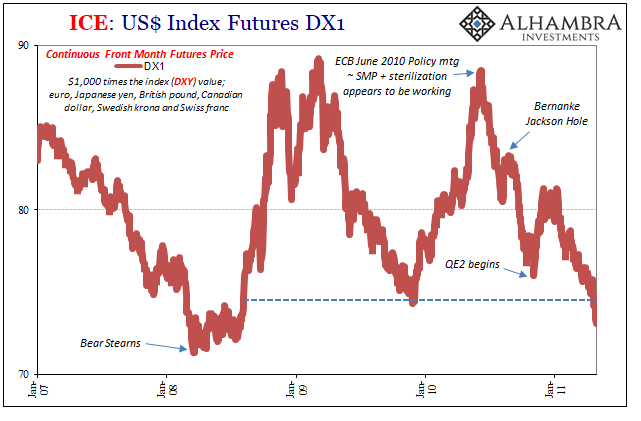

He issued that guidance just a few months before the dramatic recurrence of another dollar crisis. Not one caused by its substantial downfall, of course, but another global liquidity problem which once more provoked the exact opposite all across the spectrum; bond yields fell sharply, the dollar rose, and even stocks for a time were hit by dramatic liquidation.

Not only that, by March 2011 the Federal Reserve was already more than halfway through its second round of QE. Why? For most people, including Buffett apparently, it was easier to focus on the “money printing” part for what it wasn’t than to ask what it was that had the year before forced Ben Bernanke’s reluctant hand (and then would do so again the following year in 2012).

The world had a dollar problem but not one that would send it plummeting, or inflation ever skyward. Milton Friedman showed conclusively that the direction of interest rates is often in contradiction to the mainstream views on them – lower rates is tighter money, not the other way around.

What’s ironic about Buffett’s minor role in the history of them over the last decade is that his firm, among the other big firms, has been behaving exactly as if this was the case. In the non-financial corporate sector, post-2008 liquidity preferences have ruled all decision-making often at the expense of productive investments among other economically beneficial trends.

The on-the-ground experience during the 2008 panic permanently altered the corporate landscape, both financial as well as non-financial. Funding markets (commercial paper) stopped working, and standby bank credit was revoked without warning, leaving even the biggest and most creditworthy names in a very precarious position. As I wrote last year on the topic of corporate liquidity preferences:

What you do is never put your business in any such situation ever again. You stress endlessly all the ways such micro failure might never be repeated. If you can’t trust banks for them having yanked away emergency credit lines (as so many businesses found out at the worst possible moments), commercial paper markets for reasons nobody could fathom (and most still can’t), or really any other typical standby approach (because they were always connected in some ways to banking, meaning eurodollar), then you hoard liquidity yourself. You self-write your own liquidity needs so that you won’t ever again be put into a situation facing the prospects of having to layoff workers not just because of a downturn but because there is no cash and no way to get it.

In his most recent shareholder letter, Warren Buffett writes about just this sort of thing in his own firm now almost a decade after it had happened to everyone else.

Charlie and I never will operate Berkshire in a manner that depends on the kindness of strangers – or even that of friends who may be facing liquidity problems of their own. During the 2008-2009 crisis, we liked having Treasury Bills – loads of Treasury Bills – that protected us from having to rely on funding sources such as bank lines or commercial paper. We have intentionally constructed Berkshire in a manner that will allow it to comfortably withstand economic discontinuities, including such extremes as extended market closures.

So, what was Buffett talking about in early 2011 in making such a statement (as well as others) against UST’s? He had, like so many others, fallen victim to the mainstream narrative about normalcy. If you ignored everything that popped up starting in late 2009 indicating that things still weren’t right even if the green shoots of recovery had simultaneously appeared, the risks would seem to be on that inflationary side of the ledger. Though he had no duration in his holdings (sticking to T-bills as opposed to the long-dated instruments he professed disdain for), he did himself (and others) little favor.

Of course, dismissing those “other” things was a nontrivial mistake, one that policymakers keep making – as have all those who follow them so blindly. If Berkshire was self-writing what was essentially liquidity insurance, it stood, and stands, to reason that everyone else started to. The rest of Corporate America might not have engaged in such prudence before 2008, but you can bet they do now profiting from Mr. Buffett’s wise example. It’s both a monetary case as well as some of the reasons behind the constant lethargy and inability to accelerate into actual recovery (supply side productivity problems).

Liquidity preferences have mattered, and they don’t correlate at all with the QE’s except that all four of them have proven the Federal Reserve doesn’t know how to fix the dollar issue.

Here we have a prominent example (using Buffett’s legendary status somewhat unfairly against him) of how the intersection between effective money in the real economy and economic conditions can make a tremendous difference. What was supposed to have happened by 2011 was that corporations like Berkshire had shed at least some of their liquidity preferences in favor of the so-called animal spirits; embracing QE as it was in theory in disregard to its failure in practice.

If that’s the way things had gone, the dollar keeps falling and the economy gets back to normal with inflationary rather than deeply deflationary risks. Has anything changed since 2011? According to what Berkshire Hathaway still does rather than what it’s chief Buffett occasionally says, not really. Hoarding cash is tight money action, even if intermittently markets take to trading on the contrary words.

Stay In Touch