In October 2006, the Communist Party of China unveiled a landmark new policy aimed at easing social and societal unrest in the country. The Chinese leadership would strive for a “harmonious society”, reaching this goal no later than 2020. As one of the final works for 16th Party Congress convened in 2002, it would stand as the template for how the 17th Party Congress would attempt to rule.

A year later, in October 2007, Communist Party leader Hu Jintao built further upon that foundation, stressing harmony if in the background of all the Party’s major initiatives. In many ways, he said, the Chinese were fortunate in being given the opportunity to address any issues from the position “of this new historical point.” Rapid economic expansion had radically transformed the country.

Economic strength increased substantially. The economy sustained steady and rapid growth. The GDP expanded by an annual average of over 10%. Economic performance improved significantly, national revenue rose markedly year by year, and prices were basically stable. Efforts to build a new socialist countryside yielded solid results, and development among regions became more balanced.

The key pieces of the harmonious society were to be democracy, rule of law, equality, and environmental stewardship.

Of the first, democracy, it was a particular point of emphasis in Hu’s speech opening the 17th Congress. China will “expand people’s democracy and ensure that they are masters of the country,” he said. Mentioning the word repeatedly, 60 times according to the Chinese embassy in the US, it would mean increasing transparency as well as “opposing or preventing arbitrary decision-making by an individual or a minority of people.”

For many of the poorest Chinese, there had been an upset in balance. On the one hand, rapid economic growth had presented them, as Hu referenced, with opportunities never before experienced in modern China. It had come with a cost, though, where quality of life was more and more uncertain. In his speech, the Communist Party Chairman observed:

Our economic growth is realized at an excessively high cost of resources and the environment. There remains an imbalance in development between urban and rural areas, among regions, and between the economy and society.

Harmony, then, was to be certain that economic growth would expand society’s progress along all lines, and that a stronger commitment to democracy would assure that those on the wrong end of China’s transformation would have more than a voice in achieving this melodious future.

One delegate attending the Congress in 2007 was much more forthright. Wei Jiafu, president of China Ocean Shipping, said simply, “It’s easier said than done. In some places solving pollution problems brooks no delay. Only after economic growth juggernaut is completely discarded across the country can we breathe in fresher air.”

The country in recent years has taken a darker turn. The 19th Party Congress held last fall still held high the goals of environmentalism if by default. Gone, however, was harmony at least as it was understood by the dictates of the 17th Congress and the last plenum of the 16th. Stressing other features, the balance has apparently shifted in another direction.

Officials would have anyone believe that it is by choice, that Communist officials have seen enough of air pollution and water disaster to reverse decades of economic priority. That was never the goal, however, certainly not of the harmonious Chinese society. It had been a challenge to find a way for the country to have both; rapid economic growth as well as recognition of, and attention to, its downsides.

It seems by 2017, there had been only attention to that latter state, and in more ways than one. Xi Jinping, Hu’s successor in 2012, spoke repeatedly not of democracy nor economic growth, at least not as it had been for a quarter century. Instead, he referenced, a lot, the word “rejuvenation.” As I wrote at the time:

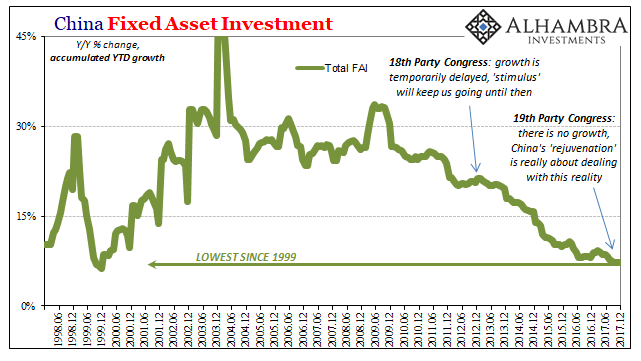

Xi proclaimed a “new era” where the quality of growth would be the priority over quantity or speed. It sounds good until you think about it, as anyone with common sense knows that quality comes from speed. The rejuvenation part was nothing more than making it seem as this was the plan all along; the official version of “oh, hey, we meant to rebalance this whole time.” Only there isn’t any hint of rebalancing.

The 19th Party Congress ended with Xi Jinping’s name added to the Communist Constitution, no small thing where his will stand alongside only Mao’s. To achieve this curious rewriting meant cutting off any opposition. To go against Xi now is to go against China itself.

For totalitarian states this is the standard order (and for a good deal too many “democracies”, too). A leader is always looking to tighten his grip on political power because despite the love affair for authoritarianism (especially in the form of technocracy) in the West that kind of system is uniquely fragile. Like an organized criminal operation, the real danger is most often from within the power base rather than from the people outside of it.

The big question was not “why” but “why now?”

Xi, apparently, hasn’t stopped moving yet in that same direction. Over the weekend it was reported in Chinese state media that the Communist Party Central Committee is preparing to further amend the Constitution in order to remove restrictions against Xi serving more than two terms as President.

China is governed by a trinity of powerful offices. The President is but one of those, the others being the Communist Central Committee General Secretary (the political head) as well as Chairman of the Central Military Commission. Eliminating any limit on the President’s ability to serve in that office at the same time as holding the position in the other two, according to Party officials, will “help maintain the trinity system and improve the institution of leadership of the CPC and the nation.”

The article also wryly observes, “The change doesn’t mean that the Chinese president will have a lifelong tenure.” No, but it does open the door for the possibility. Now that he can, what are the chances Xi Jinping won’t?

It isn’t final yet, of course, and there is the possibility that the government will change its mind if reaction is harsh and stiff enough. Still, why now?

It is an obvious 180 degree about face from the 17th Party Congress’s commitment to China’s harmonious society. If completed, this would be a further anti-democratic maneuver, just the sort of “arbitrary decision-making by an individual or a minority of people” leadership was once committed to ending.

My own view is rather simple. The Communist Party apparatus really appears to be gearing up for what the final end of the economic miracle might really mean. You crack down on opposition before the opposition becomes trouble. It’s hard not to guess that in looking at China’s future political and social state absent the growth many have become accustomed to, Communist officials sit aghast at the very real possibilities. Their economic options have run out on them.

The Chinese people were willing to bear the environmental burdens so long as it meant a prosperous present. Take away the future prosperity from hundreds of millions still waiting for it, and that changes entirely the balance or even breaking point. If social unrest was a major issue in 2007, how about 2020 missing one-half of the harmony equation?

For many here in the West they won’t be able to fathom this transformation, nor its potentially grave implications. How can they? They’ve spend the last ten years talking about a recovery that the rest of the world knows never happened. It is in the weakest links of the economic chain where the consequences of that situation are most relevant. Thus, what I wrote at the conclusion of my thoughts the last time apply here, with this latest political development only adding to its weight in evidence.

In the West, “we” can’t make out the economic risks because the political class has forbidden it as a legitimate topic. And so in that respect the world over here is perhaps further along in the wrong direction politically than even China. To be clear, I’m not suggesting authoritarianism is the answer, only that the Chinese at the very least appear to be approaching the world as it is from a far less idealized, imaginary even, perspective.

In other words, China is not the only place where political risks fueled by dangerously stretched out economic dysfunction are rising. It is but the first and perhaps most obvious example of historical uniformity on the matter. These things do not ever end well, typically in the kind of authoritarian counter-backlash that is among the worst of the worst cases (the true worst case is where the newly installed authoritarian decides to use the full range of his powers).

The global economy is booming, so say Western economists. The Chinese Communists are outwardly smiling along in agreement with them, all the while battening down the (political) hatches at home. We still talk about 2008 because, sadly, it isn’t yet over.

Stay In Touch