Back in October, we noted the likely coming of two important distortions in global economic data. The first was here at home in the form of Mother Nature. The other was over in China where Communist officials were gathering as they always do in their five-year intervals. That meant, potentially:

In the US our economic data for a few months at least will be on shaky ground due to the lingering economic impacts of severe hurricanes. In China, the potential for irregularity is perhaps as great, though it has nothing to do with the weather. In a little over a week, Communist Party officials will gather for their 19th Party Congress.

The temptation may exist to deliver a somewhat better economic picture than has been the case. The government spent a whole lot in resources betting on if not straight economic growth by now than at least a plausible path to it. So far in 2017, China’s economy, as the global economy, has not come close to living up to expectations.

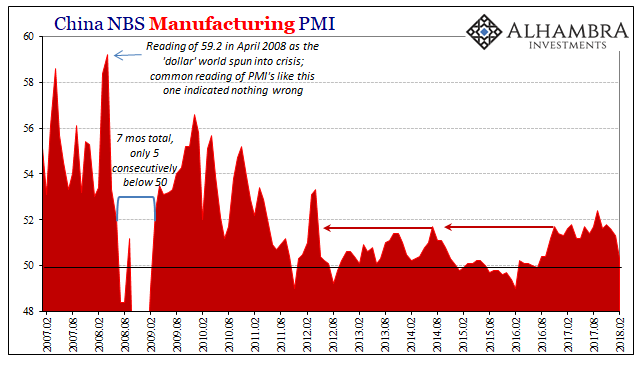

The specific reason for writing all that was China’s official manufacturing PMI. The National Bureau of Statistics had reported that day a rise to 52.4. Released just ahead of the 19th Party Congress, though a relatively low level for China it still represented a pleasant-sounding 5-year high.

And, predictably, it was taken that way particularly in the Western media that presumes this globally synchronized growth. Since that simply cannot occur without China’s participation, if not emphasis, the hype was strong. That particular PMI number, however, was dubious to begin with.

Four months further on, the manufacturing PMI has dropped in February 2018 to nearly 50 again. From 51.3 in January the current estimate is just 50.3, registering both the largest decline in years as well as the lowest level going back to the end of the last downturn in the middle of 2016.

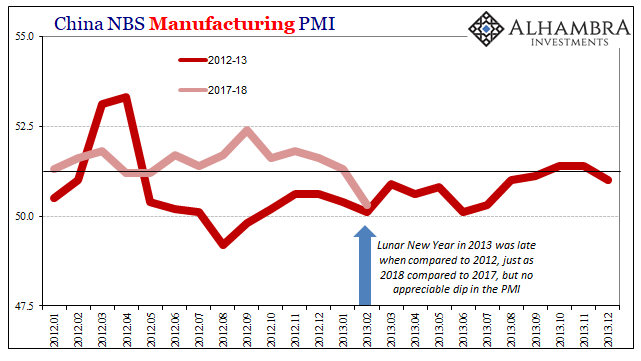

We have to be careful given China’s Golden Week situation. Government officials have already suggested that the late Lunar New Year in 2018 as compared to 2017 (it fell in both January and February last year) may have distorted this particular reading. That may be the case, or it may have had a partial effect, but if it is it would be the first time.

February 2013 was similarly disturbed by its later Golden Week when compared to 2012. Yet, China’s manufacturing PMI in that month declined only slightly and wasn’t at all out of line with either past indicated performance nor, more importantly, how the rest of that year developed economically (not good).

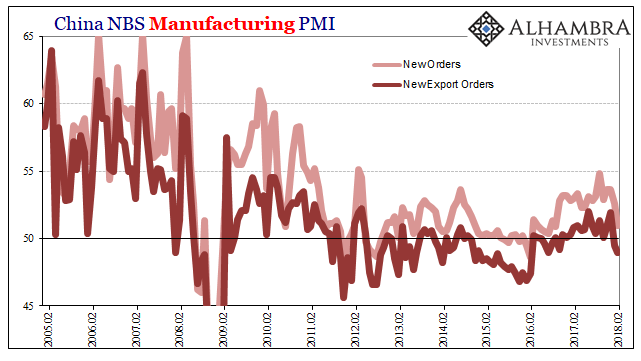

The internals of the latest reading also figure on the wrong side of globally synchronized growth. Keeping in mind the New Year situation, still the index for New Orders dropped to 51 from 52.6, while New Export Orders declined to 49.0. The latter would be less impacted by the Golden Week, but more than that the index for New Export Orders was already just 49.5 in January. This doesn’t suggest a statistical problem so much as a potential real one originating outside China out in the rest of the world.

The culprit may be exactly what we stated back in October. There was always the temptation to perhaps push forward economic activity ahead of the Party gathering, to put more of a positive spin on China despite, as I wrote before, an entirely disappointing 2017 to that point. As with so many other statistics in so many other places, symmetry continues its absence.

The other factor might at first seem hard to believe but more and more does appear to provide perhaps a probable explanation. Though those two storms were limited to just the Gulf region of the United States, it really does seem as if there were outsized impacts across the whole globe. I don’t think there was much of an actual boost in orders and production, though there was surely some.

More so, I believe, it was this constant narrative to the point of hysteria. These minor upticks in already slightly positive figures had the practical effect of making it seem like maybe there was something to all the global growth chatter. Expectations are central to orthodox economics for a reason, as they can have a powerful effect on conditions.

But, contrary to the Economics textbook, they will at most leave temporary impressions. People in business who become cautiously optimistic could do more in anticipation, but they are still cautious for a reason. We might feel better about things given those accelerations in data and how they are perceived in the mainstream, eventually, though, real activity has to follow on a sustained basis.

As I’ve taken to writing more frequently, at some point the boom has to boom. It cannot stay in narrative form for long. Aberrations, true anomalies like hurricanes and political theater, aren’t going to provide a broad enough basis for that to happen. If this is indeed how it eventually plays out going forward, then it will have proved to be actual hysteria. In some places it will also have been intentional. China isn’t the only one (see below) where such deceptiveness might have been applied.

Stay In Touch