Residual seasonality isn’t a residual, but it is seasonal. The concept was introduced several years ago mostly because Economists were finally being embarrassed about their meteorological predilections. It had become common, far too common, to blame snow, cold, and general wintry like conditions during the winter. Thus, something else had to be brought forward to explain why what looked like a weak economy each and every Q1 couldn’t have been a weak economy.

What was hit upon was this residual seasonality, the idea that there was some quirk in the statistics for especially GDP that unfairly subtracted more in any Q1 than was reasonable. The Bureau of Economic Accounts (BEA), the keepers of GDP, disagreed initially but conducted a study anyway. The conclusions of that study also disagreed, but they enacted residual seasonality anyway.

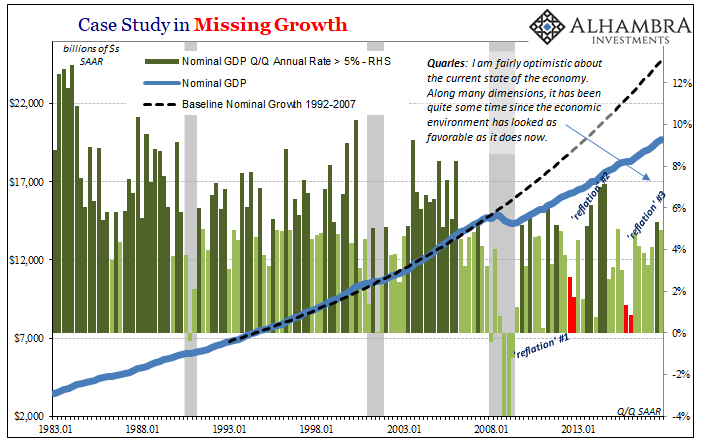

And still the economy stayed weak, only for much more than any single Q1.

The problem was never too much snow nor statistics. The hitch has been Christmas. Americans, as is their choice, love to splurge during the holiday season whether or not doing so is a wise decision. After having broken slightly from prudent practice, by the beginning of the following year consumers have to pay for what they had just done by foregoing in the first part of any year additional spending; ipso facto, figurative residual seasonality.

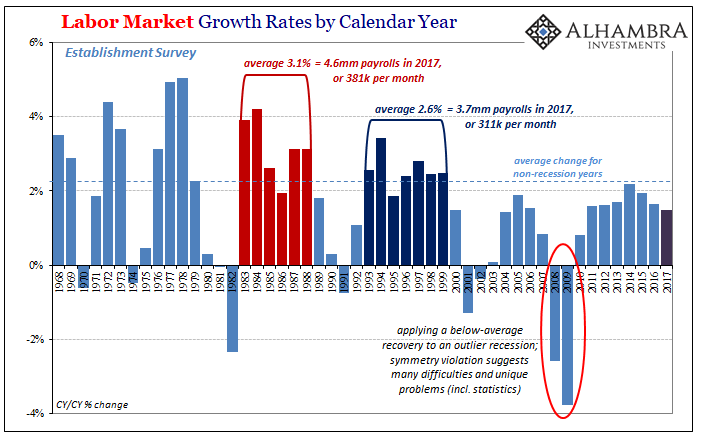

It is, of course, somewhat inaccurate to blame a holiday any more than it is to blame a season. It’s not the fault of Christmas nor where it always falls on the calendar. The big deficiency continues to be, year after year, lack of income and labor market growth. Both are gaining, but positive numbers do not necessarily equate to actual, meaningful growth.

So it begins again for 2018. Retail sales estimates released in the middle of last month for January were predictably down on a seasonally adjusted (as well as hurricane aftermath aftermath) basis. Unusual snows were once more blamed, as if people who can’t go out for one day or perhaps two will just spend less over an entire month for the physical weather impediment.

The BEA in its Personal Income and Spending estimates today says that Real Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) likewise declined in January, an economic account that encompasses a more comprehensive suite of consumer spending (including on services). Again, snow, winter, and residual seasonality have been mentioned.

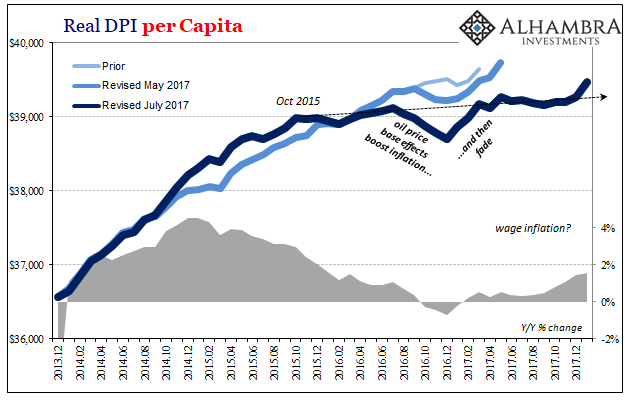

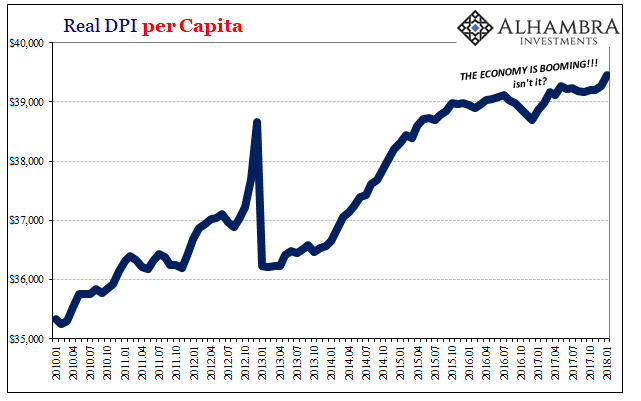

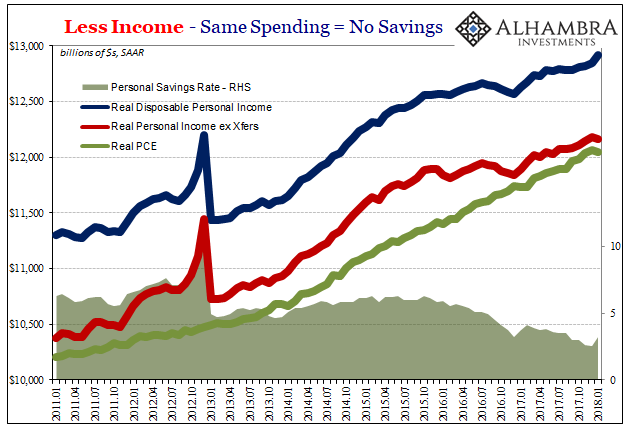

As is usual, the problem remains income. Though the initial effects of December’s tax reform and cuts are clear in some of the data, they aren’t nearly as large as the rhetoric surrounding them (which was at times considerable). Real Disposable Personal Income per capita gained 0.5% in January over December (seasonally adjusted). That was the largest monthly increase since October 2014. Still, the year-over-year increase was just 1.56%, nearly the same as the (upward revised) 1.46% in December and 1.09% in November.

All three of those rates owe more to base effects (comparisons to falling real incomes in later 2016/early 2017) than tax cuts. If it takes all of tax cuts, base effects, and whatever little there is of economic advance just to get 1.46% growth, that’s not a good start for all the hopes pinned on tax reform.

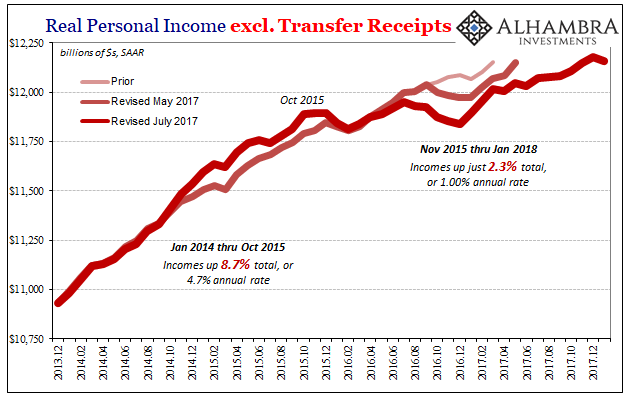

While income viewed from this format rose in January, the more basic, economic measure did not. Real Personal Income excluding Transfer Receipts fell (seasonally adjusted) in the month from the one prior. Year-over-year, incomes were up just 2.2%, again on base effects. Excluding them, over a longer period of comparison, shows just how ugly things have been the past few years since the last downturn.

Through all of 2014 as well as 2015 up to and including October that year, Real Personal Income excluding Transfer Receipts had gained 8.7%, or 4.7% at an annual rate. Over the 27 months since, it has increased 2.3% total, not per year. That’s an annual rate of just barely more than 1%.

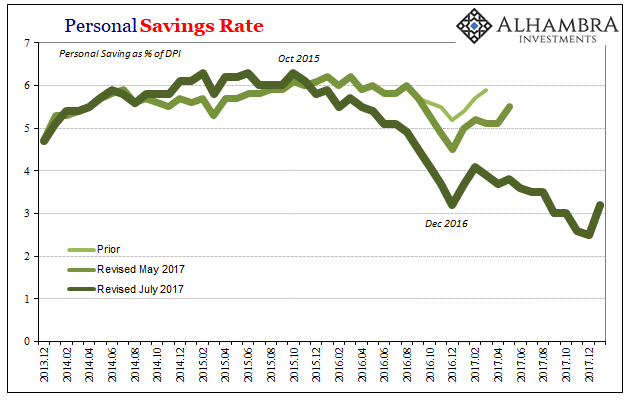

Spending, however, hasn’t slowed by nearly as much. The intersection between spending and income is, of course, savings, which can only have meant a precipitous drop in the savings rate. Starting in the second half of 2016, that’s just what appears to have happened.

Falling still further in 2017 given the continued weakness in the labor market, as well as, importantly, the utter lack of promised, proclaimed, and much talked about wage acceleration, by last Christmas US consumers had pushed themselves into a tight spot. Either incomes were to rise, or holiday spending would produce problems yet again in time for Q1.

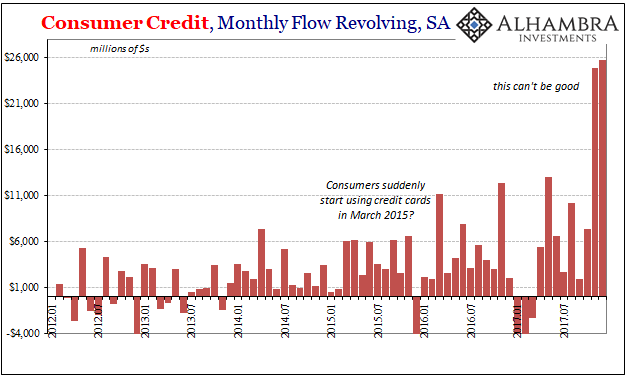

This condition was very likely made more aggressive by unrelated data suggesting in both November and December a very large increase in revolving consumer credit – if you don’t have either income or savings, borrowing is the only option left for marginal spending. Those credit card bills will have started to show up at some point in January, with the rest to have arrived in February and extending so long as incomes remain stagnant.

This is neither weather-related nor residually seasonal. It is, still, seasonal but primarily in how that creates a bottleneck of sorts given the labor market and the unfulfilled promises over acceleration in wages first before overall pay.

It always starts with earned income, right where the problem has been all along. Baby Boomer retirements and the opioid crisis didn’t break economic symmetry in 2009, nor did they do it again starting in 2016. What is it that adds up to inflation here? If we are right back to residual seasonality for the nth time, it’s not that there isn’t a boom it’s that there can’t be one.

Stay In Touch